Before you read on, we have a favour to ask of you. If you enjoy this feature and are currently OK for money, can you consider sparing us the price of a pint or a couple of cups of fancy coffee. A rise in donations is the only way tQ will survive the current pandemic. Thanks for reading, and best wishes to you and yours.

"Choice tune selection is vital, of course, but the durable mix goes way beyond that. It will evolve and mutate, sonically, but within its own identifiable idiom. It will also, in its sympathetic tapestry of tracks, evoke quite specific moods, atmospheres, places and memories. It will make a statement."

Tony Naylor, The Guardian

Almost everything in music criticism is subjective. Obviously the more people who share an opinion, the more persuasive it becomes, but there are still people out there who hate The Beatles. However, one thing that stands up, pretty much whoever you speak to, is the identity of the greatest DJ mix album of all time – that accolade goes to Coldcut’s incredible 70 Minutes Of Madness, their offering for the Journeys By DJ mix series, released in 1995. The wildly inventive mix, which incorporated hip hop, techno, funk and drum & bass (along with the Doctor Who theme tune and a host of crazed spoken word samples), redefined what a DJ mix should be, perfectly capturing the cut & paste ethic of the mid-90s in the process, while arguably inventing what became the pop mash-up. It was subsequently featured in The Guardian’s 1,000 Albums to Hear Before You Die – one of only four mix albums to feature on the list. “The standard by which all DJ mix albums are judged,” said the journalist Dorian Lynskey.

Before the release of 70 Minutes Of Madness, the DJ mix album had mainly been a straightforward, linear affair, with records (usually house and techno) laid down one after the other, seamlessly (sometimes shabbily) beat mixed together, perhaps with a lull in the middle, but often just a relentless march of uptempo bpms leading towards a crescendo, like Michael Douglas and Sharon Stone’s passionless rutting in Basic Instinct. The thing that makes 70 Minutes so special, is that when it was beamed down there was really nothing around to compare it to, and since, with the exception of the Radio Soulwax series and some of the more accomplished deck technicians operating in the hip-hop sphere (Format, Cut Chemist, Shadow etc), nothing and nobody has come close. It is as distinctive in its sound as an artist album; a painstakingly created work of art, but sounding fresh, spontaneous and loose. It was, as Tony Naylor says, writing in The Guardian in 2010, "a Damascene moment… a shocking illustration of how boring mainstream, mid-90s dance music had become".

Coldcut are well versed in innovation. With good reason they called their first record label Ahead Of Our Time. They were the first UK act to build a completely sample-based record (1987’s ‘Say Kids (What Time is It?)’), inspired by the works of Double Dee and Steinski, and Grandmaster Flash’s ‘The Adventures Of Grandmaster Flash On The Wheels Of Steel’. Coldcut were the link between old school hip hop and acid house, as demonstrated by their groundbreaking Solid Steel radio shows for Kiss FM, which started in the late-80s (and were recently re-launched online). They were hip hop remix pioneers who had big chart hits in the 80s before retreating to the more inventive fringes of electronic music with their ever-excellent label, Ninja Tune.

"It’s a drunken man’s stagger home,” says the unassuming Jon More of 70 Minutes Of Madness, when we sit down to discuss the mix in the confines of the Ninja Tune offices over cups of tea, almost 20 years after its release. We are joined by More’s gregarious and outspoken Coldcut cohort Matt Black, and Kev Foakes, aka DJ Food, and Patrick Carpenter, aka PC, the other warped minds behind the mix. "If anything qualifies for the journey cliche, it’s this," says Black.

The roots of the mix are in Solid Steel, the radio show you used to do for Kiss FM that started in the late-80s.

Matt Black: London in the 1980s was where multiculturalism was really coming on strong. You had youths of different colours and backgrounds who all wanted to party together, but weren’t catered for in the normal clubs. So that was where the London warehouse scene came from. Jon was a major figure with The Meltdown and Flim Flam and he used to play a really eclectic fucking mix of stuff. He had Test Dept. play live and then he’d chop into an Afro record. It was a really diverse set of sounds that was reflecting where London was at at the time. It was a really significant time. The melting pot was heating up.

Kev Foakes: Remember, this was pre-Acid house as well.

MB: Exactly. We’re talking early/mid-80s, before the whole acid house and ecstasy thing took off. Kiss FM was a pirate station and at that point it represented what London wanted to listen to. There was Jon and me, Jazzie B, Trevor Nelson, Joey Jay, Norman Jay, Tim Westwood and David Rodigan – we had all the best DJs in London on this station, which was inspired by Kiss FM in New York. I remember going there in 1979 and hearing the Kiss FM Mastermix Dance Party, and I thought that was a wicked phrase. Tuning into those and hearing what could be done by sequencing records together to keep the party going – layering records in the conventional BPM style of mixing. A couple of years later there was also the emergence of those records like ‘The Adventures of Grandmaster Flash on the Wheels of Steel’, and Double Dee and Steinski. They came from the hip hop style of mixing, but they took it further from just scratching over a record, or cutting two breaks together, to make a new art form. So those records were very exciting to us and we really wanted to do something like that. That was what came out in Coldcut’s first record, ‘Say Kids (What Time Is It?)’. That was us wanting to copy those records, but with Kiss, we had a platform where we could take that idea and extend it over a couple of hours, rather than just five minutes on a piece of vinyl. Also, those records were illegal because there was no way of licensing a DJ mix at that time, but on the radio you were allowed to do that. Though, of course, Kiss was a pirate, so we weren’t really allowed to do it! But there was a precedent for DJs being able to play and mix records on the radio. So that was an exciting, new channel that was available to us – to be able to play with records and put that out to an audience.

KF: How many DJs on Kiss were actually mixing as well?

Jon More: Paul ‘Trouble’ Anderson.

MB: Trouble was a very good mixer. Judge Jules was.

KF: But weren’t they just mixing one style?

MB: Well, Trouble was great – I can remember hearing him mix World’s Famous Supreme Team with Masterdon Committee, and go-go records with 110bpm stuff. He was pretty flexible. He was an inspiration. I can remember talking to Norman Jay about scratching and he just laughed and said, "Oh my little son can do that." So I thought, right I’ll show him. And we did ‘Say Kids…’ and that proved that it could be used more creatively.

JM: Most of the DJs talked in between each record, but we didn’t. Well, a bit, but to us it was all about the music. We were always under pressure to talk and as Kiss became more commercial, when it went from pirate to commercial, there was more pressure for us to adopt the standard ways of the radio DJ. But we managed to resist.

MB: I always used to find DJs talking over records immensely annoying, especially when I was trying to tape the records off the radio in the 70s. I’d be like, "Shut the fuck up, I’m trying to operate the pause button here!" It was a reaction – we didn’t want to be those guys, so by using jingles we could keep the thing going, and we knew that people would be into that as a seamless musical experience, rather than the jarring DJ having to inject themselves into it.

JM: Sometimes we even managed to persuade the station manager to allow us to have a two-hour ad-free broadcast, which is what lead into the Journeys By DJ mix.

Solid Steel was a weekly show. How did you go about conceptualising it each week?

PC: I started working with Jon and Matt at the beginning of the 90s, and they encouraged me to do mixes for the shows. They were broken up into 15-minute slots and that was quite groovy because you could stick a jingle at either end and then you had 15-minutes to do your thing. It broke it up into manageable chunks to throw in whatever you wanted and that was a really useful format.

MB: So yeah, initially we used to do, say one or two 15-minute mixes…

JM: Or sometimes it was just one that we’d prepared. So there would be lots of ambient, not just what you would consider “classical” ambient, but jazz, industrial…

MB: And then we could play records and slurp from one to the next. It didn’t all have to be intensively worked out. But when Patrick came on board, that coincided with the ability to do these longer shows, and by that time we had a little studio up in Livingston Studios in North London so we would set up there with turntables, but also synths and echo chambers as well.

Patrick Carpenter: And an 8-track tape machine…

MB: So then we had the facilities to be able to start doing things that were more multi-threaded.

KF: This is all pre computer editing and all that. I think our Journeys By DJ mix was the first thing we ever computer edited.

JM: It was yeah.

KF: I started on Solid Steel in 1993, and sometimes it would be all four of us and we’d do half an hour each. It would all be completely improvised and we’d just bring a bag of records – what we’d bought that week or what we wanted to play…

JM: What was going on in the clubs…

KF: We would pre-record it on a Friday and it would go out on a Saturday. It would literally be hit the button and we’re off, as if we were live.

MB: We were recording it on DAT, and you can’t edit DATs, so it had to be right.

KF: We’d punch the ads in off cards. And we had this thing called Word Treasure, which were CDs of as many spoken word phrases or sound bites or monologues that we could fit on one CD. They would be punched in as well, so it would be like, "Oh we need a horse here" or…

MB: Yeah, or we need a "something" here. The advent of the CDr meant that we could make our own custom jingle CDs. When I first met Jon, he developed this technique of getting cassettes and cutting the leader out and reassembling them so that we could record a jingle on it and it would instantly start playing, without the gap. The CDr took over from that, so we’d gather loads of weird stuff. We made Word Treasure 1 and Word Treasure 2, which each had 99 tracks on them and then caned them for the next few years.

Where were you getting all the samples from?

JM: I’d accumulated a lot of spoken word records.

MB: Jon particularly had a good collection. He sometimes used to play whole bits of spoken word, like a Superman episode on his Kiss show.

PC: Matt, you’d tape stuff off the TV quite a lot.

MB: Remember The Ninth World? Also Temple of Psychic Youth – it’s a Psychic TV offshoot – had quite a mad catalogue of stuff and we used a lot of that.

KF: Alex Paterson turned you onto The Tape-Beatles didn’t he? They were an offshoot of Negativland, who used to loads of spoken word/collage stuff.

MB: The Orb came and did this show with us and they were using this CD and I was like, "Fucking hell, this stuff’s amazing!" And I found out it was The Tape-Beatles, who were collage artists and had made this amazing CD with loads of stuff that they’d sampled and then chopped up into abstract-ish pieces that you could easily ladle over other stuff or use as links. There was also this thing – Church of the SubGenius. At the time, they were like a very hip, funny, stoner, American anti-religion. They used to do these media barrage tapes. I got some of those and they were so intense… very out there. It’s one of those things you hear that just rips your head open and gives you a load of possibilities for what you’re doing.

JM: We found stuff to use everywhere. We just seem to have an ear for a ridiculous phrase.

MB: Steinski would trace it back even further, to those crazy records in the 1970s, where people just used to edit together loads of stuff about UFOs and…

KF: What were they called? Cut-ins?

MB: Yeah. If you listen to ‘Soul Power ’74’, by James Brown and Maceo, you’ll hear a Martin Luther King speech floating over…

KF: And then a baby crying.

MB: It was really ahead of its time.

KF: ‘Revolution 9’ by The Beatles – that’s a massive collage.

MB: Steve Reich.

PC: Lee Perry.

KF: Mikey Campbell had all that stuff like, "The Dread at the controls!" That was all useful fodder that we could recycle. Those guys were already using spoken word in a really interesting way. But Steinski for me…

JM: He’s the don.

MB: His choice and his technical ability – Double Dee as well, to give him his due – the way it was done. It was finessed so well, but their choices really opened people’s minds. Before then you wouldn’t think to throw in a bit of rockabilly or Marlon Brando or whatever.

KF: When I first heard Double Dee and Steinski’s ‘The Lessons’ that was pretty much the blueprint for everything I went on to do. That whole aesthetic – like Flash’s ‘Adventures On The Wheels Of Steel’ – y’know, you’re taking the best bits from everywhere and making them into something else. It didn’t matter if there was some pop in there, like Junior or Culture Club, which generally I hated, but the fact that it was mixed in with all that other stuff… Bugs Bunny and Clint Eastwood.

MB: There was a certain kind of stoner humour thing going on there that was like, "Oh yeah, you could put that in! That’s so cool!"

KF: A lot of those spoken word things were like that. We were laughing at them and were definitely putting stuff in there for the heads. The show used to go out between 1am and 3am – prime smokers hour, trippers hour, whatever you want to call it. So many people I meet say, "Oh I used to listen to that back in the day, I was out of my mind!"

JM: I met a guy recently who said that they used to record it on cassette and then go to Dover Beach and take acid and listen to it.

MB: There’s a guy called Rob The Funky Human Being who said that his mates used to trip while they listened to it and remix it at the same time with their own voices and echo chambers and stuff.

It was such an amazing, vibrant, creative thing – were there any other artists working along similar lines?

KF: Negativland were doing it over in the States, but they were doing it in a more politicised way. They did tapes of their shows and it was much more hardcore than what we were doing, because we were erring towards the dancefloor side of things. But they were very heavy on the spoken word and more industrial music. They were the only ones who were doing it at the same time.

When it came to do the JBDJ mix, did you approach it like a Solid Steel show, or did you alter your working methods?

JM: It was just such a series of random consequences. Everybody came up with their own section for the mix, some of which were little routines that been honed at the club nights we used to run.

KF: I certainly pulled out a couple of things that I’d done in Solid Steel mixes and in clubs and added them in. Like the thing where the record gets turned down from 45rpm to 33rpm – that was one of my little club tricks to change the tempo. I remember Matt saying, “It has to be the best mix ever, or at least the best Solid Steel ever…”

MB: I had quite a competitive and confrontational attitude to things. I’m constantly amazed at how satisfied people are with so little. That really pisses me off. So when Tim (Fielding) phoned up and said, “Would you like to do a Journeys By DJ,” I thought, “This is really a chance to show those bastards how it should be done” – what could be done. Coldcut was at a bit of a low ebb at the time, so I wanted to strike back. Show those motherfuckers what a mix is actually about and what DJ culture is actually about. So it was quite a clear decision to do that and we had a lot of assets and energy to draw on with what we’d been doing with Solid Steel.

JM: It was a kind of post-house reaction, because I think there’d been an excessive amount of house mixes prior to that.

KF: At that point pretty much all DJ mixes were pure house or techno.

MB: Or maybe a jungle one. It was just so pathetic. Ninja Tune had already established itself as the resistance against “McDance”. It was a strange thing because we loved house music at the time of ‘Acid Trax’ and ‘We’re Rockin’ Down the House’ – that was some raw shit right there. So exciting. But it very quickly turned into a commodity. I think we would have had a much easier life if we’d just gone with the flow, but we didn’t. And Ninja Tune was a posse of people who were not satisfied with that being the only musical dish on the menu. So all these other mixes having been house mixes was the perfect opportunity for us to make the point.

KF: There were four of us and we were all coming from very different angles.

MB: It was a group mind thing. I don’t think any one person could have done that.

KF: At the start we pooled our records and made a massive bucket list, most of which they couldn’t license for whatever reason!

MB: We mixed first. Then they went for permission.

JM: That had an effect on the course of the mix. For example, quite ironically, we couldn’t get the rights to ‘People Hold On’ (with Lisa Stansfield), our very own tune, off Sony – they refused to allow it. Patrick used to do this wicked mix with that and Moody Boys’ ‘Free’ and that was up as a potential… Moody Boys did end up on it, but ‘People Hold On’ didn’t.

MB: There was a Leftfield track we couldn’t get either, ‘Original (Jam)’, so we had to put Air Liquide on instead.

JM: But we had access to most of the material we wanted, and our Ninja material, so we stitched it together using that.

KF: There was quite a lot of current material though. ‘The Bridge Is Over’ (by Boogie Down Productions) was mixed in with Photek.

There’s a lot of jungle and drum & bass that very much roots it in that period.

KF: But with, say, that Junior Reid a capella over the top, it brings it out of just being jungle.

When you play it on iTunes, the display says it’s just one song, but there’s actually three playing at the same time.

PC: Technology still can’t handle it.

It’s been so painstakingly constructed that it feels more like an artist album than a mix album.

MB: It’s kind of a comment on the interface between DJing, mixing and studio production.

JM: It was assembled almost in a way that Model T-Fords were. In parts, basically.

KF: Yeah, yeah! It was definitely stitched together.

JM: But we were limited by the technology.

KF: We only used a computer to edit it at the end. The multi-layering was all done on an ADAT.

JM: We were limited to two 40-minute ADATs, so then we had the problem of joining those two together… thinking how the first 40 minutes would end, and how the next 40 minutes would begin. Kiss FM had got some computer editing software for radio and we copied the two sections from the ADAT and loaded them into the computer and joined it together. We did it up in the studios of Kiss.

MB: A disc jockey plays records, a DJ plays with records. So we came in playing with records. Then something like Flash, ‘…Adventures On The Wheels Of Steel’, showed that you could use those techniques to make a new piece of music, by collaging other stuff together so we started doing that. But then suddenly we found ourselves in the producer’s chair, in a studio with a 24-track – initially just using decks, but then expanding to drum machines and sequencers and synthesisers as well, so that became more like a normal music production. So it was kind of a fusion really, of recording techniques and aesthetics.

KF: ‘Wheels Of Steel’ is apparently live, but this mix was never going to be live. We did mix loads of it live, but it was done in sections and then patched together.

MB: ‘Wheels Of Steel’ is live, but ‘Lessons 1, 2 And 3’ isn’t – they were done on an 8-track. So we already knew that once you got to certain level of complexity you couldn’t do it just using DJ techniques. You needed the studio tricknology to be able to build up the layers.

KF: Nobody had made a mix CD like ‘Lessons…’ People had made live mix CDs where they’d just played records in one session, live, end to end. But we were doing the layering thing for 70 minutes.

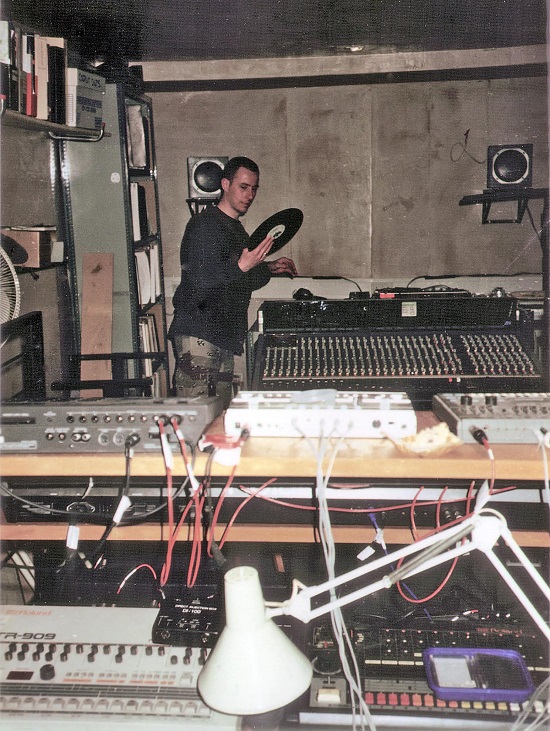

Kev Foakes at Clink Street Studios

I’ve always thought that 70 Minutes… was responsible for some of the first mash-ups, for want of a better term. Joanna Law’s ‘First Time Ever’ acapella over Luke Slater, Junior Reid with Photek. Were you pioneering that technique of fusing disparate songs to make a new one, or were you following someone else’s lead?

JM: Eno did it with David Byrne – My Life in the Bush of Ghosts – so that DNA seeped into our work because we’re such big fans.

KF: I think the mash-up analogy is a bad one. It’s misleading really, because what happened with mash-ups and that whole bastard pop thing, is that that’s just what DJs did anyway. They just mixed two records together of different types and, if they were really, really different, they created a third. That’s what we’ve always done.

MB: Actually, I think you can trace what became the mash-up back to our work. There’s a link to what we were doing, and back beyond, that we’ve laid out. It’s when this idea of mixing two records together to create a third went mainstream. That was when it got a label – mash-up. And bastard pop – the pop in there tells you that it was taking what was effectively an underground technique and applying it to mainstream music. Because we liked to consider ourselves underground – and were quite snobbish about it – generally we wouldn’t use pop references because it wasn’t cool. We liked to think we had much cooler points we wanted to make. But ‘Last Time Ever’ is in the pop canon, and it worked so well. Later on, people weren’t so scrupulous. Fair play – in fact, a lot of great mash-ups came out of releasing the snobbish hold on that.

KF: And they’re almost the best ones. When you’ve got something so pop and something so underground, which should never be seen in the same room – like the Kraftwerk/ Whitney Houston one by Girls On Top. I can remember when it first came out and I was DJing and worried about playing it, wondering if it would clear the floor. But I played it and everyone loved it. That was when I knew it was going to be a craze.

MB: I worked out belatedly that if you were going to mash things up then it was a good idea if people knew what the ingredients were. So like on ‘Say Kids (What Time is It?)’, the best bit is James Brown’s ‘Funky Drummer’ with ‘I Wanna Be Like You’, because everyone knew The Jungle Book. It helped us as DJs to surrender to popular taste and not be so snobbish about it.

JM: And it also helped to make people more accepting of disparate elements coming together if it worked. A lot of those moments are accidents. We’ve all had times when we’ve turned up at a club and just put two disparate records together and gone, “Ahh, that works!”

MB: Or played a record at the wrong speed, and just gone, “Fuck it, gotta go with it!”

JM: It’s a bit like when you trip over in the street and style it out.

Before 70 Minutes… came out, how did you feel about it? Was it the statement that you hoped it would be?

MB: I was pretty happy with it.

KF: I think we were pleased with it.

MB: My mate’s film tutor once said that films are never finished they’re just abandoned. I think we felt a bit like that. Things can always be added to, but we let go of it at a point where we felt that we’d made the statement that we wanted to make. It was good enough. Things aren’t always successful just because they’re really good. They exist only in connection with a whole lot of other factors. The time for the mix was absolutely right. There was a latent requirement for something like that.

KF: Which is what we were reacting to…

MB: That’s right. We diagnosed that. We made something that filled the hole that was there. Not cynically – we were just doing what we did.

The reviews on release were incredible. How did you feel about the initial reaction?

KF: There was nothing else like it out there. It was existing at number one in a field of one.

Which is why at the time, I used to play it over and over again. Because it would finish and you’d just think, “That was amazing. What else is like that? Um, nothing, I’ll just put it on again.”

MB: I don’t really trust journalism. I’ve seen so many things applauded because one or two people say this is great and then everyone else thinks, “If we don’t say this is great, we’re going to look stupid and like we don’t get it.” So then they all pile on and say it’s great too – and obviously it works the other way around too. Things can just get filtered out if a few tastemakers say it’s shit. It’s not often that people are prepared to go out on a limb and say, “You’re wrong.” So journalists can be quite sheep-like, as can the general public.

I understand what you’re saying, but in this instance I think it was actually the case that you had made an exceptional mix album and people – journalists and music fans – just responded to that.

KF: It was the right thing at the right time. I think that’s all you can say.

JM: It managed to connect with a bunch of people.

KF: The time was right because we were doing back rooms – what were then called chill-out rooms. But we were essentially doing this [the JBDJ mix] in the chill-out room, because the main room was always house or techno. So when we got the chance to do Stealth at Blue Note, we transplanted what we were doing into the main room and everyone went mad for it. They wanted something like this. They wanted four turntables with everything mashed up in the main room. Hearing classic rap and hip-hop with electro, jungle, jazz, funk…

MB: I think the general public have much more freedom with their taste than they are credited with. Whereas marketing forces – “the con” as the SubGenius referred to it – that’s not convenient for them. They want nice things in nice boxes that they can stick a pretty face on and sell that “McProduct” again and again. So unfortunately those forces have quite a tight grip on the windpipe of human culture. Fortunately it is possible to wrest it off them if the conditions are right.

How do you feel about it now looking back? I hadn’t listened to it for a while, but I was amazed by how fresh and original it still sounds. That’s quite an achievement, considering how much has happened in music and technology in the intervening years. Obviously, a jungle track from that time sounds quite dated in isolation because of all the mutations that have happened in that genre, but the mix as a whole has aged really well.

JM: That’s good. It’s surprising in some respects, but maybe that’s because it is out on a limb. The main problem is that we always get asked if we’re going to make another one.

That was my next question!

JM: In a way, the question is already answered by the fact that we haven’t in this period of time. There’s always that option open, but it was an outpouring of creativity and energy that would be hard to replicate. It was born of frustration with the dominance of the commercial house music explosion that had built up over several years, and the fact that the people behind that explosion hadn’t been paying attention to the growing audience that were wanting something else. They didn’t necessarily want a diet of superstar DJs.

PC: For me it was a very personal thing. I was 25 and I had a hefty record collection. I’d just come out of sound engineering college and then I was working at Ninja and I met Kev and suddenly we were playing on four turntables – it all happened so quickly. I listen back to it now and for me, it’s a snapshot of that time. It’s not like that moment is ever going to happen again. It’s impossible.

KF: I was the last person to join. I was such a big fan of Coldcut that it was hard for me for a while to actually believe that I was doing mixes with them. I’d got over it by the point we did 70 Minutes.

MB: This question about “what next?” after JBDJ has always vexed us, as you can imagine. On one level it’s like, we did it. We made the statement. We don’t need to do it again. Now the rest of you can catch up! How could we top that? And unless we could there was absolutely no point. Just cranking out the same thing again, using the same blueprint…

KF: Another 70 Minutes of Madness!

MB: So all these years and we haven’t really done an official follow-up, though there were all the Solid Steel mixes, which were pretty good. But Coldcut didn’t do another project like that, because we didn’t really know what to do. A few years ago we did actually talk about doing it but then we thought, “Fuck it. We don’t need to worry about what other people think.” If we do it, then they’re going to pigeonhole it and say, “It’s not as good as Journeys By DJ.” So fuck ‘em. We just want to do something that we’re happy with. I did a mix that I think picks up where Journeys By DJ left off. Now the technology is on our desktops, there’s no need to worry about all the technical restrictions we had before. Again we pooled the tracks from several hundred, and using Ableton we could have unlimited tracks and unlimited effects and the ability to warp and tune music, which wasn’t available at the time. I wanted to make something that was as multi-threaded and complex as possible; something that raised the bar again. No one’s really noticed it, but it’s on Mixcloud. [It’s called Coldcut Presents 2 Hours of Sanity Part 1: Love] One of the ideas was to reference the best of what was out there in experimental music. It’s not just that these tunes mix together or that’s a good tune, it’s also that it makes a reference point as well. It refers to a bigger point by virtue of its context.

Coldcut Presents 2 Hours of Sanity Pt. 1 – Love by Ninja Tune on Mixcloud

KF: Each track is in there for a reason.

MB: That’s right.

KF: There are definitely echoes of JBDJ in the Love mix. It’s a follow up, but not a follow up.

MB: The editing is a lot more complex, and again it’s investigating the interface between DJing, mixing and studio technology – using the technology to see if we can weave two or three or four songs together at the same time. So to answer the question, what happened after Journeys by DJ, that’s my answer. It’s a personal answer, so I don’t want to come across as claiming anything too grandiose. Like I said before, it’s not that we’re that brilliant, it’s just that everyone else is crap and every time I put a record out, somebody calls me out on that. What I meant by it was that things could be so much bigger and better than they are if people would just rip it open and freak it out a bit more. The idea space is still under explored.

Why do you think it is that more people aren’t exploring and expanding the DJ mix in the way that you did? Do you think it comes down to a lack of skills? Why is there still such a dearth of ambition in the world of DJ mixes? You guys are rocking four turntables, with samplers, synths and scratching and all that, while others can barely operate their CDJs adequately.

MB: But with a simple, free piece of software like Virtual DJ you can have four virtual decks that automatically synch to each other.

JM: It’s actually easier now to replicate what we did.

MB: Eno once said that one of the ways to get noticed is to do something that’s incredibly difficult because not many people are going to be able to do it.

KF: Or can be bothered to do it. Because there’s also that knowledge thing – we’re all of an age where we’ve got 20 or 30 years of experience, and the record collections to match.

And the imagination too.

MB: I think perhaps mixing got a bit overrated. Personally, I think I’ve often been two focused on getting two records that mixed together really well, and less on playing a record that people actually want to hear. At one point there was a reaction against mixing – a while after JBDJ came out.

KF: Yeah it was like, “I’ll just play tunes man, one after the other – that’s my thing.” Fair play.

MB: Sometimes it’s just nice to leave a gap so the crowd can cheer!

KF: Mr Scruff does that a lot – he’ll play a record until the end and leave a gap. You don’t have to mix. And you do need a gap, or at least a very big breakdown, in DJ sets. It can be too relentless. That’s the art of mixing. There’s also attention deficit disorder. Even at the end of the 90s people couldn’t go for two choruses before they started to get edgy and these days it’s even worse – especially with people listening to music on their phones all the time. But you want to be doing something. The crowd expect you to do something.

But going back to the actual time it came out and the time being right – we’re now 20 years on, and Matt’s ‘Love’ mix just crept out on the internet. It wasn’t released, it didn’t have to go to be reviewed, it didn’t need a big fanfare or a cover even. The way of distributing music these days and the way things come out is different – you can download ten free mixes a day easily. No wonder Matt’s mix got lost.

MB: Have you heard this phrase “the tyranny of choice”? There’s so much music available that people can’t be bothered to wade through it so they just go for the things that are well known. Say there are 20-million tracks on the internet – but from the whole of recorded history there’s only about 100,000 tracks that people actually want to listen to. It’s a huge problem. It is great that people can make their own music and get it online, but it has a reverse side to it as well. So the beauty of DJ mixes is that they enable you to listen to a load of records in a shorter period of time. With so much music out there to wade through, that’s more important now than it’s ever been.