A near deserted shoreline. Steam from a train passing by. A nuclear power station dissolving in the mist. The lighthouses, vast sentinels. Maritime objects, scattered. A ship graveyard. The shingle tumbles underfoot towards the shoreline. It would be actual suicide to swim. You thought you knew the sea but it is moving like you’ve never seen before, sideways, violent, completely deranged. Sea deities are often the gods of sunken treasures. In Viking myth, for instance, the goddess Rán, mother of the waves, drags ships down with her nets. Her name means ‘theft’ in old Norse; she takes their goods and their lives while she’s at it. A scan of a wreck map of these islands reveals we’re surrounded on all sides by a catastrophe of remnants, strewn over the seafloor.

In the last years of his life, the filmmaker Derek Jarman would walk along the shingle of Dungeness, where he lived, and pick through washed-up objects. He would take them back to Prospect Cottage and arrange them in a surreal garden oasis, plants and metal growing together. What the sea had plundered was returned transformed. As for objects so too for lives, with Jarman noting the metamorphic aspects of illness upon him in film and text, with the final transformation to come, echoing Ariel’s song in The Tempest, “Full fathom five thy father lies, / Of his bones are coral made, / Those are pearls that were his eyes, / Nothing of him that doth fade, / But doth suffer a sea change, / into something rich and strange”.

Decades ago, there were risks to being even gothic-adjacent in peripheral cities. Yet there was knowledge too of layers below. It seems absurd now but – like their friends in Nurse With Wound, Einstürzende Neubauten, Current 93 and their predecessor Throbbing Gristle – Coil felt dangerous. Everything about Coil suggested they were on their way to a netherworld; theirs was an esoteric quality that hinted at some dabbling in the Dark Arts. Compelling, confusing, intimidating. It didn’t arrive with just the standard fear that your parents would hear the lyrics through the floorboards but rather you the listener would unlock forbidden irreversible things. Music as a Lament Configuration. To be filed next to books you’d read that might cause a face to grow out of your spine in your sleep or a portal to purgatory appear in your backyard. Such fears were, given the austere times, irresistibly attractive.

When I encountered Coil, they were nothing like I’d expected. For years, they were unobtainable. You were as likely to find a Coil record in the local Woolworths cassette stack as you were a screaming mandrake in the grocers. The absence only added to their mythos. Then one day, surrounded by body horror b-movies, I finally found them, courtesy of the film An Angelic Conversation. The images were spellbinding and, as with all of Jarman’s Super 8 footage, spoke of life lived at an entirely different speed, with the heartbeat of iambic pentameter accentuating the visuals, a “dream in the face of a world of violence“. The (homo)eroticism of Shakespeare’s sonnets illuminating a modern gay love affair. One sequence in particular, elegiacally ruminating on beauty and time, took hold: “To me, fair friend, you never can be old, / For as you were when first your eye I eyed, / Such seems your beauty still”. The music, however, introduced another aspect – vast shadows moving below the shimmering water’s surface. The soundtrack, at that point, was terrifying in a way that metal or goth feigned but never reached. Instead, this was a threnody, the dying cries of a creature in a prehistoric forest or wind screaming through ancient subterranean machinery. It was insanely beautiful and to this day I have never heard anything remotely like it.

‘At The Heart Of It All’ is the black hole centrepiece of Coil’s debut album Scatology. Given the apocalyptic impact AIDS was beginning to have, with friends, lovers and collaborators (Jarman was all three) suffering and dying way before their time, the song feels less a portrait of mortality itself and more a depth sounding, echoes escaping the abyss without their bodies, a rage against the dying of the light. This was Coil’s angry amphetamine album by their admission. The warm embrace of MDMA and Blakean dancefloor visions some distance from seeping into their music. In early 80s Britain, there was much to be angry at. A case in point was their pre-Coil origin story. One half, Peter ‘Sleazy’ Christopherson, had a Mephistophelean C.V. including COUM Transmissions and Throbbing Gristle. He took the first photographs of the Sex Pistols, uniting Arthur Tress nightmare, psychiatric ward evaluation and rough trade advertisement. He’d designed the infamous BOY window display, featuring the (fictional) incinerated remains of a juvenile trespasser. He’d even been smuggling high weirdness into the public consciousness via co-founding membership of Hipgnosis, responsible for the covers of Wish You Were Here, Animals, Houses Of The Holy, Peter Gabriel’s first three solo albums (sadly, Paul McCartney rejected Sleazy’s suggestion of “a man hanging himself, surrounded in gold leaf, in the style of Gustav Klimt” for Tug Of War). Respectable by daytime and last days of Rome by night, Sleazy was part of TG’s “wreckers of civilisation” according to a speech in the Houses of Parliament. “Anything less, I’ll be sorely disappointed”, the heroic Cosey Fanni Tutti has reflected and consider what civilisation meant in establishment Britain then. Or more succinctly, consider the allegations about Sir Nicholas Fairbairn the Tory MP who’d said it. If this was civilisation, what part of it deserved not to be wrecked?

Coil was initially the creation of Geoff Rushton aka John/Jhonn/Jhon Balance, a young fanzine maker who founded Stabmental with a schoolfriend Tom Craig, to document Throbbing Gristle and similar musical outliers. He joined Sleazy as lover and collaborator, first in Psychic TV and then Coil. If their first EP How To Destroy Angels, was a mild provocation, their debut album Scatology was an affront. There were at least two sides to Coil. Balance always denied involvement or pointed to alchemical explanations of turning shit, not lead, into gold. Sensitive, philosophical, associative. Sleazy pondered, by contrast, “the dubious pleasures of being lashed to a toilet bowl”. An accompanying press photo shows a handsome sad-eyed Balance next to a figuratively, or otherwise, shit-faced Sleazy. Here was the electric charge of transgressive culture (Lolita, 120 Days of Sodom, Salò etc.) Was it an experiment in the limits of taste, a satire of sadism and depravity, or shock for shock’s sake? Either way, it remains as transgressive now as it ever was, a rare feat, and Scatology remains more eye-catching than the working titles Poisons or The Erotic Form Of Hatred. For those disgusted by civilised mainstream hypocrisies, then and now, it was gold.

It also encapsulated Coil’s modus operandi. They displayed openheartedness towards esoteric ideas (they called their recording studios the Bar Maldoror after Comte de Lautréamont’s seminal outsider text) and supposedly wicked practises. The former were occasionally macabre and sexually lascivious, though tempered with humour, humility and a sense of ‘come and see…’ Inspired by Man Ray’s Monument to D.A.F. de Sade, the cover is a riposte or bookend to Gustave Courbet’s controversial The Origin of the World, the most NSFW of 19th Century paintings. The album notes show their erudition and generosity, though they’d later be more cryptic, with a passage from The Unspeakable Confessions Of Salvador Dali comparing his excreta to mythic and metamorphic forms. They write about the “humanism of the arsehole” with all the levelling intimations therein – pleasure, shame, secrecy, abjection, deviance etc. In case that’s all too tasteful, the first pressing came with their ‘Anal Staircase’ image.

There’s music playing within, beckoning us up the spiral stairs. It’s a peculiar, inviting mix of sounds. Initially, it sounds a hundred years old, like The Caretaker if his focus was on anxiety rather than melancholy. Then an industrial loop begins, a mecha construction beginning to move. An overture for what’s to come, it instantly establishes collage as one of their strongest tools, not just in the generation of new juxtapositions but in the Burroughs/Gysin sense of cutting up the past for the future to prophetically appear in ways the practitioner wouldn’t have expected. It was made on a Fairlight CMI, a pioneering sampling machine beloved of Kate Bush, a major influence on Balance who claimed Coil’s early work belonged eerily to the same ether-space as The Dreaming. The track’s title, ‘Ubu Noir’, refers to earlier salvage washed ashore. It originally belonged to Alfred Jarry, an absinthe-sodden absurdist, pataphysician and mythos-cultivator. Legends persist. He lived with owls. He used a revolver as a bicycle bell. He lived on the third and a half floor of a tenement. His work contained messages from the afterlife, sex machines, antichrists, despots and bears. His play Ubu Roi sparked chaos from its opening word. Yeats reviewed it in despair at the coming anarchy, “After us, the savage god.” An invitation as much as a condemnation.

Following another forefather’s instructions (Blake’s “the road of excess leads to the palace of wisdom”), Coil’s dedication to extreme sensations wasn’t restricted to pleasure. To be committed involved unpleasantries. Fear and rage squall through ‘Panic’. Balance’s canine sneer cleaves through dated keyboard stabs and button mashed synthetic handclaps. It’s cathartic and unshackling. Aided by JG Thirlwell, what’s radical about Coil at the outset is their commitment to genreless freedom, with little indication of what would follow. ‘Panic’ might be claimed as industrial, synth pop or post punk yet sits uncomfortably in each. With hilarious belligerence, Coil were disgusted by the “This is a chord. This is another. This is a third. Now form a band” sanctimoniously ‘authentic’ and retrograde side of punk, calling it the “coward’s way out”. Instead, you could make music out of anything and in any conceivable form.

The album notes connect ‘Panic’ to Gysin’s Let The Mice In, “I summon little Pan: not dead”, revealing the overlooked origin of ‘panic’ – pertaining to Pan, the hedonistic frenzy-inducing pagan god of the woods and orgies, hinting at society’s fear of Dionysian urges and passions. The duo elaborate that it’s not destructive necessarily but restorative, “Panic is about the deliberate nurturing of states of mind usually regarded as dangerous and insane. Using fear as a key, as a spur, as a catalyst to crystallise and inspire. It is about performing surgery on yourself – psychic surgery – in order to restore the whole being, complete with the aspects [that] sanitised society attempts to wrench from your existence… a murder in Reverse.” Again, the Coil sense of balance (not moderation but the collision of opposites) is at play. A philosophical sense of healing and truthfulness married to pummelling ritualistic sonic BDSM. No pain, no gain.

‘At The Heart Of It All’ follows. Scatology is almost ‘eschatology’ as often pointed out and co-conspirator Thirlwell has alluded to wanting to make the last ever album before the apocalypse. It’s hard to imagine an example more fitting for ‘last surviving song’ than this; Stephen Thrower’s clarinet wail tearing a rift in the fabric of existence. Perhaps though, it’s not a black hole at all but instead a tool and symbol that recurs throughout Coil’s discography – the obsidian scrying mirror, of reputed Aztec origin, belonging to the alchemist, occultist and necromancer John Dee through which other times and places and entities could be reached. Coil’s obsession with magic permeates their entire career but Balance was always careful to state that their use of sigils and spells were protective rather than communicative. You did not know what you might be channelling in extending the human senses into other realms. Dee’s story is a cautionary one. The historical consensus is he was a naïve polymath/crank and his partner Sir Edward Kelley was a con-artist. Kelley narrated visions to Dee, yet he was put through such repeated stress Dee worried he’d lost his mind or that the angels he was conversing with, in their own Enochian language, were demons who sought to possess him. Dee was particularly disturbed by the “horrible heresies” they spoke, that Jesus was not God, there’s no such thing as sin, and so on. The dark side of the angelic conversations. “COIL know how to destroy Angels” went an early boast but what if it’s not angels you’re dealing with? Even if you believe these aspects of the metaphysical to be bullshit, it’s still worth considering its impact on one’s psychological state, especially allied to other vertiginous paths of excess.

It may come down to a question of temperament. Balance fondly recalled Jarman joyfully giving him his first grimoire (by the artist Austin Osman Spare). He remembered Jarman dancing, despite being blind with AIDS and waving a walking stick, to Coil’s ‘Disco Hospital’, proof of the artist filmmaker’s inspiring ebullient personality. Balance was more saturnine and his vocation to, as Rimbaud put it, “long, gigantic and rational derangement of all the senses” (via sex, drugs, magic) was initially a means of receiving and transmitting inspiration but it carried risks. Scour the tideline for treasures but don’t go in the water.

If Scatology showed Coil at their rawest, it also showed the confines of that approach. Joined by Gavin Friday (Virgin Prunes) on vocals, ‘Tenderness Of Wolves’ is a suitably sexy vampire Eros and Thanatos croon. It reveals a Hobbesian view of nature, with an attached passage from The Selfish Gene, on newly hatched honeyguide birds, having been secreted into other birds’ nests, blindly annihilating their foster brothers and sisters. Mankind are scarcely superior it suggests, given the song’s said to be inspired by Fritz Haarmann, the Vampire of Hanover, who preyed on teenage boys biting through their Adam’s apples. Friday summons Diamond Dogs-era theatrics and there are powerful parallels drawn to the AIDS crisis in the lyrics, but it’s the disturbing unidentifiable background sounds – as if recorded in a primordial cave or an intensive care ward – that capture the attention. Coil would increasingly shun polemic and shelve political agendas, seeing them, eventually, as the death of art and individual conscience (which Shakespeare knew), aiming instead towards hallucinatory ambiguity, the barely explored subconscious, the sidereal approach of Austin Osman Spare, and the exhilaration of being uncertain.

At a time beset by a dubious creed of empathy, it’s invigorating to hear the warped waltz of ‘The Spoiler’, where the idea of “walking in another’s skin” is less about compassion and more about possession. Its power is in the uneasy and unexplained: “Old man’s eyes (in a young boy’s face)”.

Burroughs’ influence is acknowledged. Ah Pook Is Here – a collaboration with Malcolm Mc Neill – a key text and the impact of chancing upon Naked Lunch as a 14 year-old in Pontefract’s WH Smith, especially, never left Balance. This writing informed so much of Coil’s collage approach. Hence ‘Clap’. Named after “the action and the affliction”, a jet engine interlude complete with STD treatment instructions. Amidst the tumult, ‘Restless Day’ arrives as a surprise owing much melodically to old English folk music – Child Ballads, for example: those chill winds and deviant tales from other worlds that once existed here. The combination of dark folk with modern urban ennui, not a million miles from The Cure’s ‘10:15 Saturday Night’, is as disconcerting as the knowledge that Coil exist in the same world as supermarkets. The characterful flatness of Balance’s vocals add to a drone-like inertia, “while it seems the whole moves / every part stands still”.

Allusions spill through the rest of Scatology. Alchemy is returned to in ‘Aqua Regis’, named for “royal water”, an acid used to dissolve gold. It begins windchime pretty before a submarine pulse suggests mechanical, rather than human, life support. ‘Solar Lodge’ goes straight into the uranium-mining of taboo, via a bottomless desert pit discovered by Charles Manson, the magical organisation (notorious for The Boy in the Box case), the Black Sun symbol of the SS (these days more typically called a sun wheel or sonnenrad), and various other cults and sources of human suffering. There’s a voyeuristic electricity here but also a juvenility Coil would move away from, leaving their self-declared solar phase for the meditative moon. To their credit, the tribal/industrial track is itself a nightmare rather than gratuitous exploitation or faux sentimental concern. The power is not just from the subject itself but the inversion of society’s views of such horrors which combine salacious interest with handwringing purity.

‘The Sewage Worker’s Birthday Party’ derives from a fetish story in a Swedish porn mag (“Just before lunch several guys grabbed Steve and took him to the toilets. The Celebrations were about to begin…”). In the background are sounds from intimate gatherings Sleazy recorded. It’s an example of provocation and proclivities but also evidence of a twisted sense of humour in their work (‘120 Dalmations in Sodom’; Big Nobs And Broomsticks being a working title for a later album). It’s a threatening noisescape of pistons and motion, incessant pounding and mechanical indifference, somewhere between Kafka’s In The Penal Colony and an eventful weekend. Yet while aspects of Coil’s debut have remarkably retained their shock value, especially in a culture where the market pulls in, normalises and commodifies previously deviant territories, in order to continually expand its consumption, others that were once shocking seem merely examples of their ‘anarcadia’, revelling in the sound environments they could build around the listener and the stories around themselves.

The album finishes with a pincer movement against organised Christianity. Originally, ‘Godhead ≈ Deathead’ was ‘Ergot’ after the bread mould that caused waves of hallucinations, seizures and gangrene (St Anthony’s Fire) in medieval times. Musically a case of Teutonic pomp and arthouse suspense, it’s an anti-theist screed with some strong lines, “This is not Paradise Lost but Paradise Disowned… Virgin Mary, weak and wild / Rids herself of an unwanted child… a reign of love that stank of death”. The target is the life-negating, body-denying church but also the gloating mean-spirited puritans who regarded AIDS as a god-sent biblical plague. ‘Cathedral In Flames’ is similarly epic, camp (with gladiatorial fanfares) and heretical. Prompted by the Marquis de Sade and lightning setting fire to York Minster, it climaxes: “The youth squirmed / In a shower of gold / That etched on his skin the words: / ‘Paradise stands / In the shadow of swords’”. Coil were already moving away from the reactive, towards a mysticism partly of their own creation and partly from transmissions they had received from elsewhere. This was evidence of them finding their way; stumbling for sure but stumbling into sheer brilliance.

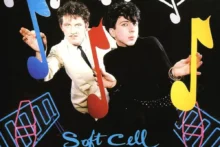

A wealth of material (‘The Wheel’, ‘Boy In A Suitcase’, ‘Pope Held Upside Down’, ‘His Body Was A Playground For The Nazi Elite’) was left off Scatology, showing how fast and wide this shadow kingdom was growing. One late inclusion on later editions though was a slow regal version of ‘Tainted Love’ featuring Mark Almond (as Raoul Revere), “the first record release ever to benefit AIDS charities”. It’s a moving piece, the lyrics morph to suggest a wild decade spent under a terrible eclipse of illness and death. The rage Coil felt was real and justified towards a repressed, ignorant and callous society, where morticians refused to touch the plastic-shrouded bodies of victims, like their friend the artist Edward Cairns (later editions of the album are dedicated to him as well as “Bastille, Leigh Bowery, Derek Jarman, Martin Burgoyne, Fritz, Steve Abbott and Leon”). Rage alone though was imprisoning, and shock came with the risk of artists warping into self-parody or nihilism, becoming pantomime or monstrously decadent, like the Viennese Actionists. Coil had a different path ahead of them. They were building a vast alternative religion with a lack of dictates but no shortage of rituals and icons. They’d pass through the end of the world to get there first; the next album was based on a vision of the Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse slaughtering their animals and constructing a earth-gouging machine from their jawbones, demonstrating they weren’t quite intending to settle down yet. It would take them far from mainstream culture, and indeed mainstream gay culture given their repeated disdain for sanitised queerness, and into enigmatic territory. Having scared away most fans of synth pop and industrial with provocation, and the weak and tyrannical with ambiguity, they were unencumbered and “allowed to mature in the dark”, sustained by a cult following (you rarely encounter a tepid fan of Coil, most are acolytes).

Neither of the pair would, to paraphrase the sonnet, live to be old. Christopherson died at the age of 55. Balance was 42. Geoff Rushton leant too far out in order to better gaze into the abyss but then eventually tumbled in himself. When AIDS closed down the sanctuary of sex, he and Sleazy had turned to clubbing and ecstasy instead. Balance took to drinking in order to take the edge off comedowns; then later, simply to take the edge off reality. The story of how, before all of this came to pass, his interest in the esoteric began really isn’t esoteric at all. It concerns a kid with German measles hallucinating in a darkened room, a boy left in a boarding school attempting to astral project. Perhaps he is – perhaps they are – now at the source of the transmissions. Coil’s body of work is sprawling, puzzling, fathomless and singular. It’s still out on the hinterlands, and the merchants of all that is tawdry will struggle to commodify and absorb it into the blob. Listening for decades now, every time I return I have to start mapping it anew, as if it is a huge continually moving glacial icefall of seracs, crevasses and wonders, never before encountered.