I was first exposed to Cardiacs’ oddly compelling world when the video to ‘Tarred And Feathered’ aired on The Tube on April 17 1987. Six musicians wearing old-fashioned vaguely military-style uniforms, covered in badly applied make-up and cranking out the most eccentric music I had ever heard broadcast on TV, against a backdrop that looked as though it had been stolen from a 70s children’s show. I had no idea what to make of it but it certainly made an impression. A friend of mine said he liked it, until he realised that the seemingly chaotic nature of the tune was in fact scripted mayhem, written down as notes and not improvised at all. This had the opposite effect on me. I wondered how someone could write such music and what on earth their influences could be.

When I briefly moved to Cambridge aged 18, my best friend there was a Cardiacs obsessive who used to terrorise his poor live-in-landlord by constantly screening their Seaside Treats video at full-throttle volume. There was something about those films – the childish petulance of the musician’s behaviour, the industrial surrealism of Eraserhead transposed instead to the garish English seaside – that I found irritating. But after a few listens, splinters of melodies had embedded themselves in my brain (abetted no doubt by the eruption of electronic mayhem that follows the command "take it Sarah" on ‘To Go Off And Things’) and resistance was no longer an option. I went out into the city centre and bought my first Cardiacs album, A Little Man And A House And The Whole World Window. Although subsequent releases by the band would mean I was forever revising which was my favourite, it was to mark the beginning of a lifelong love of their music.

Perhaps their best known recording, ALM&AH&TWWW was Cardiacs’ fourth album and the first to be recorded in a proper studio – The Workhouse in the Old Kent Road in London, which was gutted by a fire soon after. Three cassette only albums, The Obvious Identity, Toy World and The Seaside, had preceded it, along with the Big Ship mini-LP. The classic line up of brothers Tim and Jim Smith on lead vocals/guitar and bass/vocals respectively, Sarah Smith on saxophones and clarinet, William D. Drake on keyboards and vocals, Tim Quay on marimba and percussion, and Dominic Luckman on drums, was expanded to include strings and a brass section. Ashley Slater added tenor and bass trombone, Phil Cesar brought trumpet and flugelhorn, while Elaine Herman completed the picture on violin. The band’s main creative force Tim Smith produced the album, which contained the nearest thing they ever had to a hit single, ‘Is This The Life?’ Tim once told me that demand for the single far outstripped stock from the initial pressing and although he tried to get more pressed up as quickly as possible, the plant where they were being made was also pressing copies of Kylie Minogue’s ‘I Should Be So Lucky,’ and was already at maximum capacity cranking out copies of her massive breakthrough hit. A quick look at the timeframe suggests the story could have been true, but as this was exactly the kind of self-penned apocryphal tale that Tim could never resist indulging in, I’m still unsure as to whether I believe it or not.

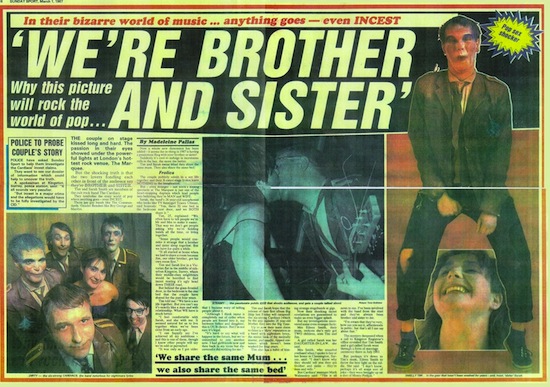

The mischievous nature of Tim Smith’s sense of humour is something that was always integral to Cardiacs’ musical and visual esthetic, particularly in the early days. A year before the release of ALM&AH, the band appeared in a double-page ‘expose’ in the Sunday Sport. At the time, saxophonist Sarah and Tim Smith were married, but Tim had managed to persuade a Sunday Sport journalist that they were in fact, brother and sister – which obviously made the kissing and hand holding on stage appear questionable. In the photographs that accompany the article, the band appear to be enjoying the joke almost as much as the free publicity, but then again maybe the journalist was a fan and in on it all along. The deployment of this sense of humour sometimes confused people who were new to the band. I once saw one outraged punter railing against the friend that had brought him, saying, ‘They’re just laughing at us’, before storming out of the gig (I should point out, he was tripping on psilocybin mushrooms.)

There was a certain element of willful perversity about it no doubt but I always felt as though the fans were laughing with the band, never that it was a joke at anyone’s expense. Late on in their career, a potted history appeared on their website which suggested that when Tim’s older brother Jim joined the band as bass player, it was his younger brother’s express wish to embarrass him by playing the most ‘tuneless racket’ possible. Then there was the fact that they took their make up tips from some very strange old ladies who they saw when they were teenagers growing up near Kingston upon Thames. All of this should be seen in the correct context. Tim had grown up on stuff like Gong and Peter Gabriel’s Genesis but he was also massively influenced by the likes of Devo, with their corporate image, and the Residents’ notion of their shadowy, self-invented record label the Cryptic Corporation, as well as the bizarre theatricality of early Split Enz and the early short films of David Lynch, particularly The Grandmother.

Critical reception from the music weeklies at the time was fairly damning. Jack O’Neill in the NME wrote: "Just when you thought Marillion had taken us to the very limit, along comes this schizo-progressive anachronism… it is the Floyd, it is Genesis, it is King Crimson, does it matter?" It clearly didn’t matter to Jack O’Neil, who like the majority of journalists at the time, were too in revolt against what they saw at the sins of the 1970s to differentiate between bands who shared very little in common other than the era in which they existed. The mention of Marillion is particularly misleading, as they represented the kind of watered down, commercialised 80s progressive-influenced music that had very little in common with either the still widely influential King Crimson or Cardiacs themselves. When Cardiacs were asked by Fish to support them on tour in 1984, the Marillion fans’ reactions said it all. Smith and cohorts were pelted nightly by a variety of missiles and even had the safety curtain set on fire during their Manchester Apollo show in December that year.

As well as inviting ire from fans of commercial progressive music, Cardiacs often confused music journalists. Julie Parish ended a live review of the band from the Marquee in London in 1986 by writing: "For those fortunate people who have not seen Cardiacs, they are directly comparable to Sigue Sigue Sputnik." Such misleading comparisons are more indicative of a journalist’s lack of imagination when confronted with something out of the ordinary, than anything whatsoever to do with the band themselves.

Whilst ALM&AH, with its full musical palette of brass, woodwind, marimba, guitar, bass and mellotron is certainly ‘progressive’ in the sense of being outside the usual self-imposed limitations of simpler pop music, many critics neglected to draw attention to other obvious influences, such as the pastoral symphonies of Vaughan Williams, or that other beacon of true Englishness, the Kinks – whose ‘Susannah’s Still Alive’, Cardiacs released as a single later that same year. In fact, a number of Tim Smith’s influences predated what would eventually become Britpop’. When that particular scene began to emerge, Tim decided it was time to revise some of his core influences, and more glam-rock nuances began to come to the fore on tracks such as ‘Spell With a Shell’ from 1999s Guns. Two other pivotal influences which often get overlooked are the English avant-rock group Henry Cow and their many offshoots (such as the Art Bears or News From Babel,) and the 1969 debut album by White Noise, An Electric Storm, which featured the talents of the BBC Radiophonic Workshop’s Delia Derbyshire. In fact, Henry Cow were such a strong influence on his music, that Tim told me he had obtained bassoonist Lindsay Cooper’s address from a friend prior to the Tube screening of Tarred And Feathered and sent her a note telling her if she tuned into Channel 4 at the right time, there would be something on that she "might enjoy".

Despite the negative reaction from many music journalists, Cardiacs always garnered praise from other creatives. English musician Alexander Tucker and the UK crime writer Cathi Unsworth both chose Cardiacs’ albums as favourites in their recent Quietus Bakers’ Dozen features. In the past, musicians as diverse as Faith No More, Blur (who Cardiacs supported at Mile End Stadium on 17 June 1995), Radiohead (who supported Cardiacs at the Astoria on June 4 1992), and Napalm Death have all acknowledged their influence. I remember once, waiting for Tim to appear outside the Venue in New Cross after they had finished a performance. I said to another of his friends who was waiting alongside me, that Tim had probably, as usual, been buttonholed by another fan who was telling him how amazing the gig had been. The side door opened and out he stepped, in tandem with the familiar face of Napalm Death’s Shane Embury, who was doing just that, effusively praising what had just transpired onstage with a far-off, mystical look in his eye.

All talk of influences aside, ALM&AH sounds like little else, either when considered alongside contemporaneous releases or against the rest of the band’s back catalogue. An eerie sense of claustrophobia pervades the proceedings. The opening strings and hissing radiator effects of ‘A Little Man And a House’ cut straight to the album’s central image; the smallness of the individual caught in the conveyor-belt machinery of industrialised society and the contrasting hugeness of the imagination that dreams of the world outside the window. ‘In a City Lining’ kicks off with a surge of mellotron and precise bursts of staccato guitar before winding itself tighter into the kind of Madness influenced singsong insanity that used to accompany the crazier parts of cult 80s TV show The Young Ones. ‘Is This The Life?’ is in some ways as atypical a Cardiacs song as you can get, its main driving melody delivered mid-tempo and unaffected by time changes. On the other hand, its massive choral keyboard sound and heavenward building guitar embody the emotional essence of the band – wide-eyed wonder and oceanic, blissful beatitude. ‘Dive’ harnesses the energy of punk to the clarity and precision of a classical symphony. As it loses itself in the mantra-like repetitive refrain towards its end, the effect is not unlike being spun ever faster on a delirious fairground ride as scary, painted wooden automatons crank out the tune with inhuman abandon.

‘The Icing on the World’ slows the pace a little once more, whilst retaining an almost mechanical sounding rhythm. Tim told me that the band had once seen Mayo Thompson’s Red Crayola play in London, and that the time stretching, stop/start quality of the song ‘A Letter Bomb’ (which appears on the album recorded with Pere Ubu personnel, Soldier Talk) had influenced them in this regard. ‘The Breakfast Line’ and ‘Victory Egg’ are equally epic in spirit, and ‘R.E.S.’ takes the kind of episodic song structure, literally crammed with notes, that Frank Zappa used on tracks such as ‘Echidna’s Arf (Of You)’ from the live Roxy & Elsewhere album, to its logical conclusion. Tim never made any secret of his admiration for Zappa but, I would argue, his own music only ever shared similarities with the absolute best of Zappa’s work – mainly that live album and the classical album The Yellow Shark. Tim Smith’s quality control was always far better than Zappa’s, and his sense of humour, far less irksome. Closing track ‘Whole World Window’ returns to a beautiful pastoral melody, not unlike something the Beatles would use at their most psychedelic. The Torso CD edition of the album contained an extra five tracks at the behest of their manager, Mark Walmsley, who insisted: ‘No one will buy the CD unless you put extra tracks on it.’ The best of these, ‘I’m Eating in Bed’’ begins with a line like sounds like it could be Cardiacs raison d’etre: "Firstly there’s a spanner in here, secondly it has the right of way", and was reinstated on the remastered edition, which came out in 1995.

That they were hated by the mainstream musical press always seemed a perverse source of pleasure to Tim, and indeed they were tangentially mentioned in said papers more than any other band, almost as a signpost of derision. For example, an interview with Tim Finn, which was otherwise largely positive, contained the statement: "Splitz Enz spawned the bastard Cardiacs." It has to be said from the onset, Cardiacs were not a ‘cool’ band in the sense of being committed to the kind of studied ‘too cool for school’ nonchalance of the singer songwriter, or your average Velvet Underground influenced British band. No, they were fully in-your-face, flat-out psychedelic and mind-warping in the tradition of Gong but filtered through the kind of pop-sensibility that XTC used to peddle in their day. Tim always said: "Music is much too cosmic a thing to become a fashion accessory." I always found it strange that a publication such as The Wire, with its far higher standard of music journalism, never picked up on any of Tim Smith’s music. I can only assume that his self-deprecatory sense of humour, combined with an unwillingness to play venues such as the Royal Festival Hall, meant that its journalists somehow felt that none of those projects warranted their often all too serious attention.

Such music, which was enormously time-consuming and meticulously spliced together, could only be made by someone who sincerely loved and believed in what they were doing. I think perhaps, for the uninitiated, there was far too much detail to get in a single sitting. I know that some of my friends thought that their music was totally chaotic, when actually it was pre-scripted to absolute precision, not a note left to chance. There were a lot of notes, however, although it was clearly still pop music. Tim’s ex-wife Sarah, who played sax in the band until 1989, said to me once that she thought he used too many ideas in one song much of the time, adding: ‘He could have easily made an entire pop career out of just one or two of those tunes.’ Tim himself once said to me, with a knowing grin: "I’m only trying to make pop music, I’m just really bad at maths." Sure, Cardiacs were always a very eccentric band, in the true English tradition, but I would argue that it is this very eccentricity (and the consequent fact that they had already arrived at utter pariah hood in the eyes of the music press) which allowed Tim Smith’s music to develop in the way that it did, unfettered by anything but the boundaries of his imagination.

In my opinion, it is the double album Sing To God that is the true masterpiece. By that time, Tim had begun to entirely transcend his influences and also had reached the point of complete self-mastery of his own studio equipment. The detail on it too, was astounding. Guitars and keyboards and drums and all kinds of sounds layered on top of each other: samples of voices that sounded like synths, synths that sounded like voices, massed string and woodwind effects from Tim’s Proteus orchestral synthesiser. And at the album’s very end, for those who were paying attention, you could even hear the man himself leaving the studio, closing a creaking door behind him as his footfalls echoed, fading away into the distance. I also rate very highly his Spratley’s Japs album, which was essentially all his own creation, despite efforts to suggest otherwise. Likewise, the Sea Nymphs And Mr And Mrs Smith and Mr Drake albums, showcased another, less manic, side to his talents.

Since such enormously ambitious music requires equally grandiose words of explanation, I would suggest that the "great grandiloquent gesture" is the essence of what Cardiacs really were about. A dictionary definition of grandiloquent reads: "Adj. using pompous or unnecessarily complex language." Yet the dictionary definition only goes part of the way towards explaining the word in the sense that I take it to mean in this context. The flipside of grandiloquence is, perhaps, "grand eloquence" – "the ability to write in a skilful or convincing way" that in itself transcends the boundaries normally placed on any specific genre or form of expression. I would also argue that Cardiacs’ music was more pomp (as in "splendour, pageantry and grandeur") than pompous.

Ok, so maybe the silliness and the surreality put a lot of people off.

But who is to say what is "unnecessarily complicated" in a particular work?

The literary likes of James Joyce and Thomas Pynchon have had this criticism levelled at them before, although I would prefer to view their work as baroque in the same sense that Cardiacs’ music is. "Baroque palaces are built around an entrance of courts, grand staircases and reception rooms of sequentially increasing opulence."

The last three words are key.

Joyce wrote the chapters of his masterpiece Ulysses in different literary styles, attempting a scorched earth policy where each chapter is such a baroque evocation of the style it emulates as to make further use of them by successive novelists unnecessary, even futile. Joyce too would have been guilty of breaking the NME convention on "less is more", which has a nice ring to it but isn’t always true. Less often is more – except when it isn’t. Try telling that to David Foster Wallace or William T. Vollmann. Sometimes more is more. To compare Cardiacs’ music to Joyce’s writing may well offend a great many people, all well and good. Having left school at 16 to pursue his muse (despite some critics suggestions to the contrary, Tim came from a working class background and was entirely self-educated in his musical abilities), he didn’t have any of the classically-themed references to put into his work that Joyce concerned himself with. His references were instead to nature (mainly glimpsed in documentaries on the TV) or to music – classical music, early 70s progressive music and later 70s punk and new wave. On the level of detail, however, I believe the analogy stands.

Cardiacs music is fuelled by love and laughter and by awe in the diversity of creation. It is grandiloquent in the way that certain classical music is – particularly the work of Charles Ives – often with several harmonies and melodies developing and converging within the structure of a single song. It can be as simple and beautiful as a budding flower, or as grandiose and multifaceted as the most baroque of architecture. Yet it is the absolute antithesis of gothic, for it is driven by the desire celebration and above all else, laughter. The kind that reaches down into your gut and doubles you up, transcending all contrary opposites and flooding you with the immediate joy truly knowing that you are alive and a part of the incredible diversity of life on this planet. And for being so, in a world that celebrated mediocrity and sameness, those who understood them, who felt this "great grandiloquent gesture" ringing true to the tune of their own souls, loved and treasured them above all else.

Perhaps the hymn they often used to open shows, ‘Home of Fadeless Splendour,’ says it the best.’

"Hail majestic corporate light,<b> Heaven born and ever bright<br> How our spirit like the waves<br> At the breath of thine awakes<br> And now the night of weeping shall be<br> The morn of song<br> "Ah! We are those whose thunder<br> Shakes the skies - the thin spun life.<br> Home of fadeless splendour<br> Of flowers that bear no thorn..."Despite suffering a heart attack and a series of strokes in June 2008, which made his body (in his own words) into "his enemy", Tim Smith remains heroically himself inside. A covers album by artists who have been touched by his music, Leader Of The Starry Skies, was released in 2010. It has been both a pleasure and an honour to know him personally. Tim will be 52 on July 3 – happy birthday fella.