To push back a genre label is, all too often, a reliably generic move by artists desperately seeking to differentiate themselves from other artists who sound much the same. Occasionally though, pushing back against genre label is a more subversive move, the mark of an artist pushing against anything that would close off their creative development.

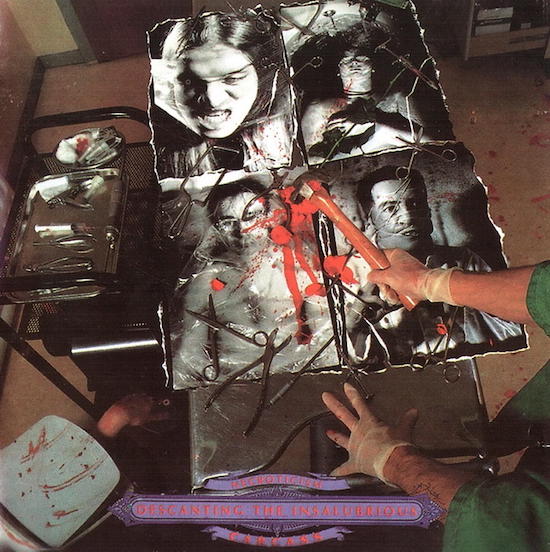

Such is the case with Carcass. It didn’t take them long at the start of their career to reject the grindcore label, they are currently rebelling against the extreme metal label, and on Necroticism: Descanting The Insalubrious they were reluctant to be labelled as death metal, preferring ‘progressive’. And however much one might put some of this down to Jeff Walker’s notoriously provocative truculence, there is a sly playfulness at work on Necroticism that marks it out from the death metal of the time.

In October 1991, there was every reason to think that death metal’s (ironic) vitality was set to become the commercial and artistic vanguard of metal more generally. Even before the pivotal release of Nirvana’s Nevermind the previous month, mainstream metal seemed exhausted and burned out. Metallica’s Black Album, while a step away from their thrash roots, showed that the 80s underground had laid the groundwork for a new mainstream. Death metal had purged itself of its ramshackle roots in the tape-trading community and the Morrisound sheen lent bands at the forefront of the scene a polished professionalism. The months prior to Necroticism saw the release of Sepultura’s Arise, Morbid Angel’s Blessed Are The Sick and Cannibal Corpse’s Butchered At Birth. Death’s release of Human, the day after Necroticism, also showed how the standard bearer of the genre could take it to artistically ambitious places.

At the time, Necroticism seemed to be part of this wave, perhaps even a concession to death metal’s dominant conventions. Through a mixture of wilfulness and accident, Carcass’ previous albums Reek Of Putrefaction and Symphonies Of Sickness cocked a snook at both grindcore and death metal. As they emerged from the underground, late 80s death metal bands seemed to yearn for a production and playing style that signified as anything other than underground. The Tampa sound was clinical, mid-range and absolutely pristine. In contrast, where Scott Burns brought clarity, late 80s Carcass brought murk. Lyrically too, Carcass pushed against the fantasies of mastery in death metal: where Tampa brought violence directed at the other, Carcass brought the destruction of one’s own body ("as my crushed bowels evacuate, much to my dismay").

Production-wise, Necroticism seemed to bring Carcass into the death metal fold. Colin Richardson’s meticulous work ensures that every riff punches through and every drum fill is timed to perfection. And as was de rigeur at the time, Jeff Walker’s bass is merged into the mid-range mix, barely audible as a separate instrument. In contrast to his bass playing Walker takes the lead vocally; his rasp easily differentiated from the rest of the mix, with Bill Steers deeper growls much less prominent than on previous releases.

Yet while the band’s penchant for strategically undisciplined unclarity seemed to have been almost extinguished, there is also something that held the band back from donning Bermuda shorts and moving to Florida. Perhaps they learned from Napalm Death’s experience on Harmony Corruption, released the previous year. So totally did that band embrace Tampa, they lost much of their uniqueness as their song-writing deteriorated into dreary mid-paced riff salads (of course, they rapidly moved away from that sound on their journey to much more interesting places, but that’s another story). In contrast, Necroticism manages to keep some distance from the rest of the pack, ensuring their style remained utterly distinctive, even if it was different from their earlier work.

Full disclosure: I’ve always found it incredibly difficult to define the source of that distinctiveness. The closest I can get is that it’s a kind of sonic raised eyebrow, a quasi-ironic drawing attention to the absurdity of it all. While anyone who’s ever paid attention to Carcass would recognise the famously wry wit of their lyrics, the way in which the music also displays a similarly wit is often overlooked. And although this sonic-lyrical sardonic fusion appears throughout Carcass’ work, it is on Necroticism that it found its most perfect expression.

You find it right from the start of the album. ‘Inpropagation’ is a spectacularly sly opening track that never quite takes you where you think it’s going to go. It begins with the first of the speech samples that preface all but two of the tracks on Necroticism, set to a kind of industrial backing. A female voice informs us of how a victim of an unexplained death is brought into the mortuary for identification. It sets the tone for the rest of an album in which causing death and interfering with the dead are depicted as activities that, while they can be fun and satisfying, are also the cause of irksome chores and annoyances. For all the filmic horror of this and other song intros, we are never allowed to forget that there is something quite silly about all of this, even as we are thrilled by it.

‘Inpropagation’ is full of unexpected byways and surprises. The song structure is hard to fathom; riffs are introduced but not repeated, leads burst in and announce themselves only to disappear. On this and other songs we encounter sonic novelties – the flange effect on Bill Steer’s line ‘I propagate’, the multiple false endings – yet somehow the integrity of the song is maintained. The musical box of tricks isn’t deployed for the sake of showing off (Carcass are not Dream Theater) nor even to disturb the listener. Rather it reminds us that this is bunch of guys playing a song about something unspeakable ("Harvesting the defouled, to fertilize my soil") and not the unspeakable thing itself. And if you didn’t get the message sonically, the lyrics constantly undercut themselves. The narrator on ‘Inpropagation’ complains that "even in the after-life there’s work to do". The song’s final couplet "Where should stand row upon row of cold grey remembrance stones/ My cash crops now grow…" borders on genius: The first line evokes the archetypal metal graveyard, the second evokes the terminology of GCSE geography.

Not all of the songs on Necroticism are as gleefully tricksy as ‘Inpropagation’. Indeed, ‘Corporal Jigsore Quandary’ in particular is an almost catchy combination of irresistible riffage. What unites the album though is the way that leads and solos are dropped into the songs in such a way that disrupts them before we can be taken to the dark places that they appear to promise. Again, I can’t pin down exactly why but the guitar leads sound ironic and sardonic. Mike Amott’s ‘Administration Of Toxic Compounds’ (titling solos is one of the most adorable things about Carcass) on ‘Lavaging Expectorate Of Lysergide Composition’ breaks the tightly-wound spell of the intro riff with an exaggeratedly spooky solo that verges on the schlocky. The portentous of the lick trade-offs between Steer and Amott on ‘Pedigree Butchery’ raise their eyebrows at what is otherwise an unremitting slice of mid-paced brutality.

Death metal and grindcore guitar solos are often dropped into the songs with little or no preparation. What makes Necroticism special is how bright, melodic and tuneful they are. These are often leads that would work in classic metal or hard rock. And when you mix such classic sounds with the blood and guts of death metal, they seem to ‘announce’ themselves, saying, ‘Hey look at me!’ We move without warning between wallowing in the decaying body and ascending to ecstasies of classic rock and metal. Perhaps, back in 1991, that was the only way that classic metal could be defended – as a kind of musical aside.

There is joy here too. If an extreme metal album can feel invigorating, fun and impishly mischievous, it’s Necroticism. It’s as though the bands were intoxicated with a sense of freedom to explore their musical toolbox. The deftly ridiculous lyrics punctuate absurd lists of real-or-made-up medical terms with lines that make you laugh or groan ("That missing piece will leave you stumped").

Of course, Necroticism wasn’t unprecedented. You can find most of the components of the album, save the production style, on their previous two recordings. But it’s here that Jeff Walker properly embraces his showmanship as lead vocalist. It’s here, no longer buried in fuzzy production, that Ken Owen really displays his technical ability. And above all, it’s here that Bill Steer starts to demonstrate that, for all his underground roots, he is one of the most inventive classic metal/rock guitarists that the UK has ever produced.

The addition of Michael Amott to the line-up was clearly pivotal in this musical coming-out party. A second guitarist gave Steer someone to spar with. And like Steer, while Amott may have been a product of the tape-trading underground, he cannot resist the call of the showy solo. On his early recordings with Carnage you can hear, as on Bill Steer’s early recordings with Carcass, flashes of the guitar hero struggling to get out of the mix.

Amott provides the link between Carcass’ journey and the journey of the Swedish scene that spawned him. From the late-80s, Sweden was the main bastion of resistance to the hegemony of the clinical Tampa sound. Albums by bands like Entombed and Dismember that were produced at Tomas Skogsberg’s Sunlight Studios eschewed the clean mid-range in favour of fuzzed-out downtuned guitars propelled by straight ahead Discharge-influenced drums. It may seem paradoxical to trace Necroticism’s roots to such a down and dirty sound – after all, the album saw Carcass move away from scuzz – but what Sweden offered was a model for a form of extreme metal that had a much closer relationship with rock & roll. Such an unembarrassed recognition that death metal was, ultimately, a form of rock, led in two directions. One was towards the ‘death & roll’ style pioneered by Entombed in the 1990s. The other was the ‘melodic’ death metal that developed in Gothenburg by bands like At The Gates and In Flames. It was the latter direction that helped to revive more classic forms of metal after their early-90s nadir.

Necroticism fed into that process of musical evolution. You can hear Carcass’ startling combination of brutal riffs and leads you can singalong to everywhere now. Lines can be drawn from Necroticism to Dark Tranquility to Arch Enemy to numberless US metalcore bands. What you won’t often find though, is Carcass’ jaunty, sarcy wit. Perhaps, the impact of the classic metal lead self-consciously raising an eyebrow to the gore on Necroticism could only be shortlived. Today it is commonplace for metal songs to switch between the melodic and the brutal without breaking sweat. Mike Amott’s more recent work with Arch Enemy has produced some good tunes, but by now there is something wearily predictable about the transition between the heads-down verse and the overblown chorus.

Carcass’s post-Necroticism journey hasn’t been straightforward. 1993’s Heartwork stepped back from death metal in favour of a more streamlined, crunchier sound. A disastrous stint with Columbia Records saw them briefly groomed for greater things, before returning to Earache, who finally released the delayed Swansong in 1996. A further step towards a hard rock style, the album showed Steer and Walker’s uncanny ability with a catchy tune on tracks like ‘Keep On Rotting In The Free World’, but Carcass’ distinctive balance between the brutal and the melodic seemed to have been lost. During their period on hiatus from 1996 to 2007, Steer and Walker both took up with bands favouring a more classic rock and metal sound.

The post-reformation Carcass albums Surgical Steel (2013) and Torn Arteries (released earlier this year) seem to owe more to Necroticism than any other Carcass album. That’s not to say that they sound the same (although Surgical Steel restored the Walker/Steel vocal pairing) but that they restored some of the band’s nimble unpredictability. That sense on each song on Necroticism that you can’t be sure what is coming next is what made it such a thrilling album. And the band are still capable of such thrills. There’s a short section about two thirds of the way into ‘Captive Bolt Pistol’, the first single from Surgical Steel, where the song suspends itself with an entirely unexpected lead that ascends and descends the fretboard with dizzying speed. The mixed reviews of Torn Arteries seemed as much as anything to be a response to the difficulty in placing what sort of album it actually was. Love it or hate it, that’s what Carcass do best.

What Necroticism gave to metal – and to death metal in particular – is a sense of possibility. Underground extreme metal in the 1980s was heart-stoppingly exciting for a while, but by the early 1990s it was solidifying into fixed conventions just as other genres have done. Necroticism is both a parody and affirmation of the genre. The lyrics represent the apotheosis of gore and a satire of it. The album showed us what death metal looked like through the prism of classic metal. It showed that it was possible to wield brutal sounds with a deft lightness of touch; to forge songs that were coherent in their sly incoherence.

All things must congeal. Necroticism was perfectly positioned in time to provide a pivot point for metal, to provide a map to multiple new directions. But today metal has expanded in so many directions that it’s difficult to envisage such a pivot point ever occurring again. Still, I know of few better examples of an album showing that songs do not have to do what you expect them do and yet somehow remain stuck in the brain.