At this point, we’re pretty much all agreed that Black Sabbath are one of our most important bands, up there with the Beatles and Kraftwerk in terms of their radical re-shaping of popular music’s sonic landscape. But it wasn’t always this way.

When I first began listening to Sabbath at the start of the 80s, their reputation was in the doldrums. For the ‘serious’ music press, they were a decrepit metal band fit only for council estate longhairs and denim-clad adolescents. Even Kerrang! were sniffy about them, the prevailing view being that they were yesterday’s men in comparison to the cream of the NWOBHM and the emerging thrash scene in LA. Their star had shone again briefly when ex-Rainbow frontman Ronnie James Dio had stepped into the breach for a couple of albums, but now, they had Ian Gillan singing for them, for God’s sake…

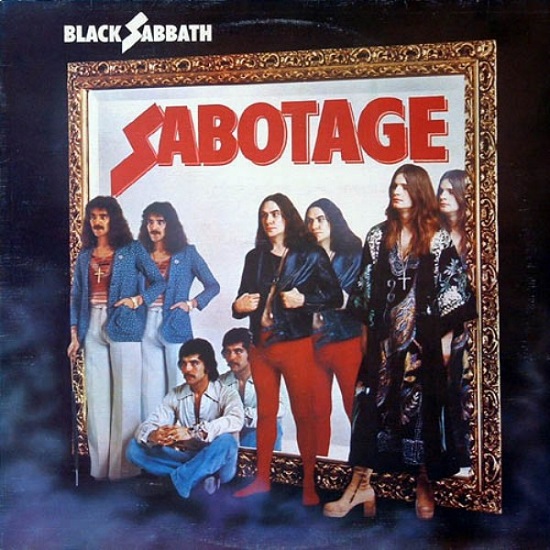

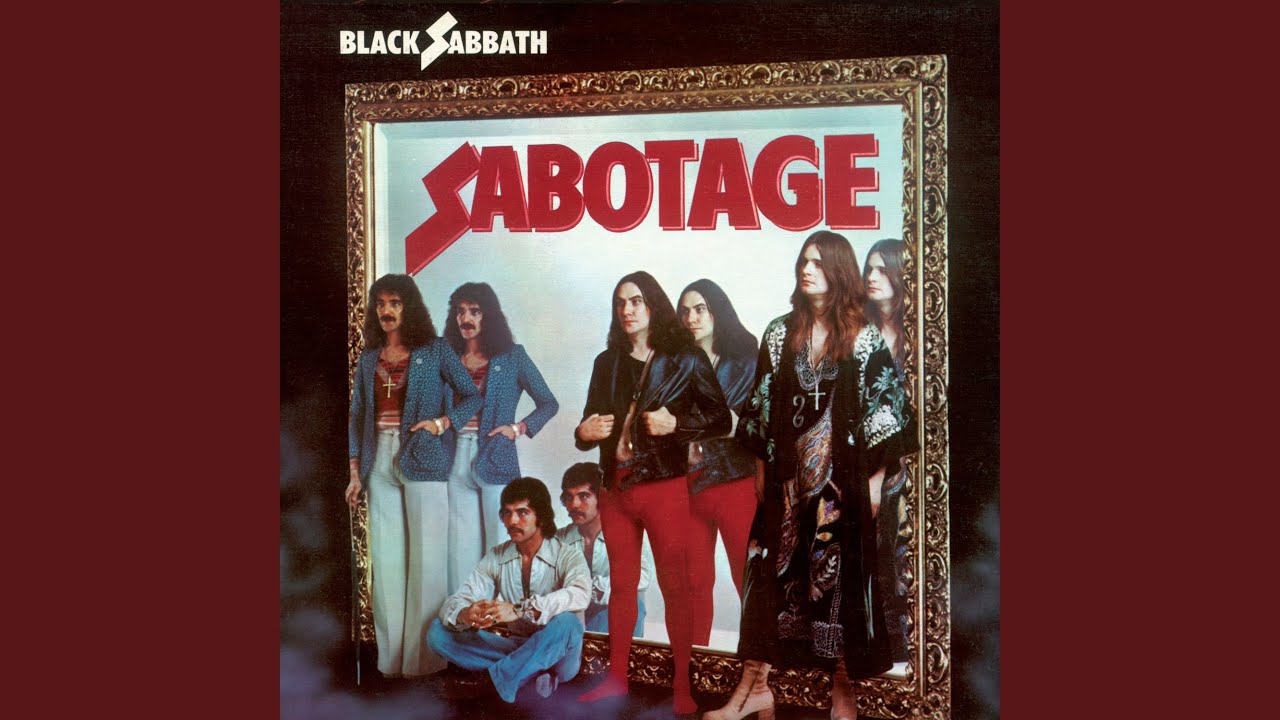

But over the past few decades, the critical consensus has slowly changed. Partly this was due to the influence of grunge (Melvins, Soundgarden, Mudhoney, Earth, Tad and even Nirvana owed a debt to Sabbath), and partly to a new generation of death/ doom/ black metal bands re-discovering once again the joys of down-tuned riffs and wailing/dismal vocalising. Out of this ferment has come the idea of the classic first six albums, stretching from Sabbath’s eponymous debut in 1970 to Sabotage in 1975.

For those of us who’ve been in for the long-haul (relatively speaking), it’s easy to feel both a sense of vindication and defensiveness when the rest of the world finally catches up with you. But while it’s tempting to buck the trend, I have to say that I’m broadly in agreement with this assessment of Sabbath’s output. I don’t think every one of these albums is a ‘classic’ in its own right, but as a body of work, they track the incredible trajectory of a band re-defining rock music, both musically and philosophically.

The thing is, nobody sounds like Sabbath, certainly not at the time and not even today. Sure, you can study Tony Iommi’s riffs and guitar tone, assemble the vintage amps, and make a pretty good facsimile of their sound (as countless bands have done). But you’ll never be able to rival the impact that Sabbath had, that visceral rending of the old blues rock order that turned muck into metal. And you’ll never have a singer like Ozzy Osbourne, possessor of one of rock’s great primal voices. Or a bassist (and lyricist) like Geezer Butler or a drummer like Bill Ward, for that matter.

It’s this essential difference from everything else around them that makes those first six albums so special. Compare them, for instance, to the two other titans of the emerging ‘hard rock’ scene at the turn of the 70s, Led Zeppelin and Deep Purple. Like Sabbath, they also had a blues-based background (with a dash of psych thrown in). But while Zeppelin inflated and amplified the form, and Purple embellished and adrenalized it, Sabbath made a giant leap for metalkind. From the moment that Iommi played the chords for what would become ‘Black Sabbath’, and thought “Hmmm, that’s a bit heavy,” they entered an entirely new musical territory.

But it wasn’t just the crushing weight of the riffs that marked them out from the crowd. It was a sense of content too. Impressive as the mechanics of much of Zeppelin and Purple’s music is, it’s never really touched my soul in the way that Sabbath do, and I think the main reason for this is because there’s something missing at the heart of these bands’ conception of themselves. Plant and Gillan’s voices might be signifiers of power and dominance (even at their most “woman done me bad” downcast), but the words they sing have barely moved on from the blues tradition itself. Similarly, while there’s plenty of ability and ambition in Page and Blackmore’s playing, it soon begins to feel like an exercise in technical prowess. In a nutshell, there’s no overriding vision beyond a desire to be the best band in town.

Sabbath on the other hand were a band that had something to articulate, a worldview born out of the grinding poverty and monotony of their backgrounds in Birmingham’s industrial hinterland. Yes, they might have initially based their imagery around a Hammer Films/Dennis Wheatley version of the occult (and what a masterstroke that turned out to be), but even on those songs that overtly reference the supernatural, there’s clearly a lot more going on than just a bunch of Brummies cavorting with the Devil.

For example, ‘Black Sabbath’ itself may well be the ground zero of heavy metal, and the subject matter of a Satanic visitation certainly fits with Sabbath’s popular image – but it’s the delivery that makes all the difference here, Ozzy’s expression of terror and hopelessness sounds like a man staring into the psychic abyss. And the sheer lack of musical uplift in the first half of the song, its relentless pummelling of the senses, goes far beyond merely saying, “Boo!” to the audience. It feels more like an encapsulation of the malign spirit of the age, the Utopian gestures of the 60s crushed by the grim realities of a new, more fearful decade.

This evocation of horror is only part of the story though. Sabbath were also unafraid to tackle in their lyrics the big issues of the day (and today for that matter), whether it’s the inequities of warfare (‘War Pigs’, of course), impending planetary destruction, both nuclear (‘Electric Funeral’) and ecological (‘Into The Void’), drug addiction (‘Hand Of Doom’), or the yoke of capitalism (‘Killing Yourself To Live’). It might not have been the type of nuanced social commentary that got the critics excited, but as an archetypal “people’s band”, Sabbath showed their audience that they gave a shit about the lives they were leading and the world they were living in. Many of their songs are about the moral choices we have to make, and those being made on our behalf (a view that the initially dismissive Lester Bangs expanded on in this piece for Creem in 1972). And frankly, you don’t get that on Led Zeppelin IV or Machine Head.

What you also don’t get is Sabbath’s deceptively unpolished sound. Now, I have to be careful here, because I’m certainly not suggesting a lack of sophistication and skill in the band’s songwriting or playing. Yet there’s a physical directness to their sound that runs counter to what the majority of their peers seemed to be aiming for. It’s more than just brute force – I guess it’s partly to do with the primacy of the riff, and a certain biomechanical precision to Iommi’s guitar work (no doubt partly due to the infamous fingertip injury he suffered, an incident that’s now deemed to be so pivotal in metal’s creation story that it gets its own VH1 animated film).

Mostly though, it’s to do with Ozzy’s voice. Like the vocal equivalent of a four minute warning, it’s a curious mix of blind panic and what-the-hell bravado, both strangely affected and completely unmannered. There’s a great passage in John Darnielle’s 33⅓ book on Master Of Reality, written in the voice of a teenage fan incarcerated in a psychiatric unit, which captures this perfectly: “No matter how many songs he sings, Ozzy always ALWAYS sounds like they just grabbed him off the street and stuck him in front of a microphone, and then either they handed him a piece of paper with some lyrics on it or he already had some written on his hand or something.”

The evolution across the group’s first six albums, from the gloom-laden blues rock of Black Sabbath to the neurotic baroque metal of Sabotage, is pretty remarkable. But even though this progression parallels a greater awareness and engagement with what’s going on in the wider music world, there’s a consistency of vision – an essential quality of ‘Sabbath-ness’ if you like – that sets them apart from the competition both then and now.

On saying that, Sabotage is definitely a bit of an outlier in Sabbath’s catalogue. There’s an impressive commitment to keep pushing at rock’s boundaries, and for the most part it still sounds great. But it’s a much more inward-looking album than its predecessors, the urge to address the world’s ills now diminished by both the circumstances of its creation and the band’s personal demons (fuelled by various drug and alcohol addictions). Instead, we get recurrent themes of mental dissolution, impotent rage and fantasies of escape, slowly going crazy in search of peace of mind. While I’m often wary of placing too much emphasis on an album’s external context – because ultimately, that’s not what I’m listening to – Sabbath were clearly not in the happiest frame of mind when they recorded Sabotage.

For a start, the band had to contend with months of soul-sapping legal proceedings before they even got round to making it, with their original manager Jim Simpson suing them for wrongful dismissal. Not only did this effectively stop them from playing live for eight months, but the court settled in Simpson’s favour, with Sabbath forced to pay compensation to him. On top of this, they discovered that their current manager Patrick Meehan had been funnelling most of their royalties into his own bank account. Geezer Butler has said, “We were literally in the studio, trying to record, and we’d be signing all these affidavits and everything. That’s why it’s called Sabotage – because we felt that the whole process was just being totally sabotaged by all these people ripping us off." (Another reason for the title was because part of the album had to be recorded again after the master tapes were accidentally wiped.)

It was also almost inevitable that at some point the band would reach a creative crossroads. Iommi wanted to keep experimenting in the studio and investigate new directions, while Ozzy hankered after the early years of knocking it out in a few days and then hitting the road. The spectre of the emerging American FM radio sound also looms over Sabotage as the band’s popularity in the US continued to mushroom (my favourite example of the apparent disconnect between Sabbath’s proto-doom metal and the stadium rock culture they were increasingly living inside is their performance at the California Jam show in 1974 – Ozzy implores the audience, “C’mon, let’s have a party!!” while Iommi stands in front of a giant rainbow grinding out the opening chords to ‘Children of the Grave’). All of which makes for an album that’s reaching out to more mainstream rock tastes (without fatally over-balancing yet) while also trying to pull new rabbits out of the hat – the fact that it’s as enjoyable, and at times genre-defining, as it is shows how imaginative and resilient Sabbath were even under considerable duress.

Sabotage begins with ‘Hole In The Sky’. There’s a little bit of in-studio chatter – perhaps to suggest a return to an earthier, more live sound – then in comes a galumphing great riff, a two chord wallop with the gait of a huge shaggy dog, the end of each bar emphasised by an air-punching “der der!” It’s a fantastic, heads-down opening, probably the most thumpingly direct, user-friendly song they’ve written since ‘Paranoid’. There’s a little bit of flash from Iommi, then Ozzy makes his entrance, his voice still great, even if he does sound that he’s on the verge of outright shouting a little more than usual. Musically, it’s a simple, good time song which nevertheless displays an air of refinement in comparison to their earlier material. Lyrically though, it reads like a convoluted cry for help, the first of many on Sabotage.

Previously, we might have expected ‘Hole In The Sky’ to be a reference to problems with the ozone layer, but here it’s just a way to get the hell out of it, “a window in time” to “take me to heaven”. There’s a nice double-tracked solo from Iommi a la Wishbone Ash, before the song segues abruptly into ‘Don’t Start (Too Late)’, a short acoustic interlude (its title comes from the tape operator’s despairing shout, Sabbath being prone to start playing before he was ready). It’s not only a nice showcase for Iommi’s finger-picking chops, but also a good illustration of Sabbath’s excellent grasp of dynamics and desire to occasionally wrong-foot their audience, all the better to once again hit them hard…

And Christ, how they hit… I was a comparative latecomer to Sabotage, not getting a copy until my early 20s. So when I first heard ‘Symptom Of The Universe’, it was across a crowded pub in Tooting, having recently arrived in London. “What’s this?!” I must have gabbled to one of my companions, but upon discovering it was Sabbath, I couldn’t quite square it with the denser, slower aesthetic I was familiar with. It just sounded so insanely aggressive, so utterly vital and so downright exciting.

Is it the ur-text for modern metal? There’d certainly been precedents for this type of angry, fast riffing before (for instance, from May Blitz and Lucifer’s Friend), but there’s a thrillingly malevolent precision to ‘Symptom Of The Universe’, particularly when Iommi’s guitar is conjoined with Bill Ward’s battering percussive onslaught, that makes me say, “Oh yes.” In particular, there’s that tiny pause in the middle of the riff that almost gives you the chance to catch your breath – but not quite. It’s the original example of the riff as a rollercoaster ride, a musical prompt that activates our fight and flight instincts simultaneously.

Ozzy launches himself into the song with an urgency and sense of mission that belies the words he’s singing, another set of hysterical lyrics from Butler that more than ever resemble the sub-poetic doggerel of a man in the midst of a breakdown (though I’ve always been rather fond of “Take my hand, my child of love come step inside my tears/ Swim the magic ocean I’ve been crying all these years”). It’s a headlong charge to the chorus, which turns out to be Ozzy singing “Yeah!” in that way that only he can, while Ward performs a series of drum rolls as though frantically charging up the batteries ahead of the next big push. Once we’ve run through it a second time, we get another brilliant riff from Iommi, a rapidly descending refrain like someone desperately scrabbling against a rock face as something unpleasant approaches. Nice minimal bass work from Butler here too.

But just as you think you’ve got your head round the track, there’s an acceleration into the distance and the sudden arrival of a completely different vibe, an extended acoustic coda with a samba-ish undertone. You might even think it was Santana if it wasn’t for Ozzy bellowing over the top about finding “happiness together in the summer skies of love”. It ends the song on an optimistic note, and features some nice noodling from Iommi, but it’s utterly incongruous with what’s gone before, as though rapidly improvised in response to a music industry demanding that they mellow out.

No matter, because ‘Megalomania’ takes us straight back into the darkness. With horror show organ murmuring in the background, its low-key intro and verse slowly advance through the shadows of a creaky old house, candlestick in hand… And then a pulverising jump-cut, Ozzy’s abject cry of “Where can I run to now?/ The joke is on me” taking us right back to the bleak heaviosity of their debut. Yet the vibe quickly descends into self-pity, the whole band lurching drunkenly along under the repeated line, “Why doesn’t everybody leave me alone?” Butler’s words conjure the image of a once-famous artist now down on their luck and morbidly brooding on enemies, both real and imagined – it shouldn’t be entirely autobiographical given that Sabbath were at the height of their popularity in the 70s, but the feeling of being out of control of their destiny is palpable.

But here comes a cowbell to sober us up! ‘Megalomania’ moves into its second section on the back of a scuzzy, crunchy riff that will go on to inspire a thousand NWOBHM bands. Ozzy pulls himself together courtesy of a double tracked vocal, his lower register voice sounding quite sinister as he sings, “Feel it slipping away, slipping in tomorrow/ Got to get to happiness, want no more of sorrow.” But then we get an up tempo, boogie-like riff of the type more associated with second division rockers such as Geordie, in no way unpleasant but slightly atypical for Sabbath.

In fact, throughout Sabotage, there’s a significant loosening of the often brutally austere approach they’ve previously taken to composition. Which is great here, but would lead to a lessening of their essential ‘Sabbath-ness’ on subsequent releases. Similarly, Iommi’s guitar is subject to phasing and various effects, as though a mutant fungus is eating away at the purity of the tone which has thus far defined the band’s sound. Still, there’s some excellent Mellotron towards the song’s climax, ensuring that side one ends on a high note.

Ah yes, records and their sides. For me, side one of Sabotage is an exhilarating, near-flawless 20 minutes of music, while side two is a little more challenging, shall we say. Although it certainly starts well.

Iommi introduces ‘Thrill Of It All’ with a mean, grating riff which he then proceeds to wail over the top of – it’s a bit like dropping the needle straight into the middle of a song. Then he lays down an even dirtier riff, a strutting piece of lumbering funk where the power is all in the spaces between the notes – it’s so dirty in fact that Ozzy is moved to utter a lascivious, “Uh!” in one of the gaps. Then the verse proper begins, driven along by a great snares and handclaps pattern from Ward. Ozzy sounds less uptight and generally happier than the previous side, and Butler’s lyrics are also more playful: “Won’t you help me Mr. Jesus, won’t you tell me if you can?/ When you see this world we live in, do you still believe in Man?”

But then there’s a peculiar sense of slippage, the song shifting up a gear with the arrival of a rather sickly-sounding synth. It takes us once again into more upbeat, rabble-rousing territory (I’m thinking Slade’s ‘Gudbuy T’Jane’ in particular), which is no bad thing in itself… but it doesn’t feel quite right. In the same way that the band’s performance at the California Jam creates a strange feeling of emotional dissonance in me, there’s something almost uncanny about this transformation into happy clappy rockstars. There’s a fine celebratory solo from Iommi at its conclusion, but West Coast sunshine seems to be winning out here over Black Country grit.

Things get stranger still on ‘Supertzar’, and in fairness, there’s no way this track could be interpreted as a capitulation to the forces of FM radio. There’s a fairly inglorious tradition of rock bands ‘collaborating’ with orchestras/classical musicians. In the 70s, the intention was to denote a certain seriousness of purpose, an indication that your compositional muse went beyond the confines of the standard band line-up; these days, it’s more likely a way to crack the Starbucks market or get featured on a British Gas advert. Back in 1975 though, you can just imagine Ozzy gawping through the control room window as the English Chamber Choir chanted along with Iommi’s slightly awkward riff, accompanied by harp and marching drums.

Sabbath have received a lot of flak for this track over the years, and there is more than a hint of Spinal Tap about it, particularly the way the secondary riff spirals up into the ether in search of a resolution. But while it does outstay its welcome, I rather like ‘Supertzar’. It certainly displays some ambition, and the voices and instrumentation actually work quite well together. Imagine it on the soundtrack to some pre-CGI medieval drama such as John Boorman’s Excalibur, or perhaps more pertinently Monty Python And The Holy Grail (released a couple of months before Sabotage), and it makes a lot more sense.

It is difficult to make sense of the next track though. ‘Am I Going Insane (Radio)’ is the main reason why Sabbath fans are sometimes critical of Sabotage (and why my best friend gave up listening to the second side altogether lest he accidentally hear it). If there have been flashes throughout the album of the band increasingly seeking some kind of accommodation with more mainstream rock audiences, then this song is the ultimate conclusion they come up with. And it’s not great.

There’s an opening fanfare of synths that you could actually lift and drop into a Belbury Poly album if you were so minded, but here, it just sounds like a naff version of Yes (Rick Wakeman having been a prominent guest on Sabbath Bloody Sabbath). If Sabbath have previously showed themselves to be masters of dynamics, all such skills seem to desert them on this song, with its ponderous verses followed by a dreary chorus. Everybody sounds a bit bored and disengaged with the process. However, is there maybe something worth salvaging here? Ozzy sings the track in a nasal drone, but what if we were to swap in, say, Brian Eno’s voice instead – that ping-ponging bass and swooning guitar in the verses could almost be off Taking Tiger Mountain By Strategy now perhaps.

A few factoids before we quickly move on: i) it’s often assumed that the bracketed ‘Radio’ in the title is an accidental reference to the view that this was the track most likely to get airplay (and it was indeed released (unsuccessfully) as a single) – but it’s actually short for “Radio Rental” ie. mental in rhyming slang; ii) Ozzy doesn’t have much time for this song, but apparently it was originally destined for a solo album he was rumoured to be making around this time; iii) those tortured groans you can hear at the end of the track are in fact the slowed down sounds of one of Ozzy’s new born children crying.

And so we come to the final track, another multi-part epic entitled ‘The Writ’. As a naïve young man, I used to think that this must refer to some kind of diabolical manuscript, the type of thing you might find in a wizard’s reliquary. As it is, it’s most likely inspired by the subpoena handed to Ozzy while on stage which initiated the legal proceedings the band endured prior to recording. Certainly, there’s a powerful feeling of pent-up fury that permeates the first half of the song.

Gradually fading up from the laughter and chaos at the end of ‘Am I Going Insane’, Butler quietly paddles at the strings of his bass, the sound oddly EQed to suggest something bubbling under the surface far below – and then POW! Ozzy’s vocal practically explodes out of the speakers, while Iommi provides righteous, almost regal, accompaniment. It’s a fabulously bolshy and confident opening, with a drop down in the second part of the verse that’s more commanding still. Unusually for Sabbath, Ozzy wrote all of the words for this song, and they’re actually some of the most cogent and affecting on the album: “What kind of people do you think we are?/ Another joker who’s a rock and roll star for you…”

This excellent first section repeats, then the pace picks up and the song moves into groovier territory. But not for the first time on side two, there’s the sense of momentum being lost, and by the time we reach the song’s second half, just about all that initial energy and ire has been depleted. It feels like some kind of MOR virus has taken hold, the track now all twinkly, harpsicord-ish guitar, while Ozzy’s impassioned and declamatory singing reminds me of no less than Demis Roussos in full-on Abigail’s Party mode. We’re a long way from ‘Black Sabbath’ here, and unfortunately it means the album ends on a bit of a damp squib.

Taken as a whole though, Sabotage absolutely justifies its place in the line-up of Sabbath’s classic albums. The cracks might be beginning to show, but it’s still packed with invention, great riffs and songs that continue to be ludicrously influential. It also represents the epitome of what makes Sabbath such an interesting and unique band in their imperial phase, and that’s their commitment to non-linear song structure, a refusal to just eke out a groove once established. They’re undoubtedly a ‘progressive’ band without ever being ‘prog’, their arrangements based on an appreciation of dynamics rather than merely implying cleverness for the sake of it. (You can see this approach similarly adopted by a number of Sabbath’s NWOBHM successors, mostly notably Iron Maiden and Diamond Head).

Then of course, we have to consider what came after this… If you’re in any doubt that Sabotage bookends Sabbath’s classic period, then have a listen to their next album Technical Ecstasy, which is the sound of a band both losing the plot and losing their bottle. It’s not dreadful, but you know you’re in trouble when your stand-out track is a piece of melodramatic sludge-psych, and three songs in you’ve got Bill Ward singing a Beatles pastiche. On saying that, Never Say Die!, the one Ozzy-era album that everybody seems to dislike, the band included, is to my ears far superior to Technical Ecstasy, if only for the absolute and undeniable FACT that the title track is one of the greatest rock singles of the 70s.

Ultimately, Sabotage is the album where Sabbath stretched themselves to breaking point. It might not have the leaden consistency of Master Of Reality or doom-pop immediacy of Sabbath Bloody Sabbath, but for its hard rock brinkmanship and the sheer ambition on display, it takes some beating.