Be-Bop Deluxe barely register in music’s critical or popular canon: under-rated by critics even in their lifetime, never really attaining proper popular success, could they be the ultimate 70s cult band? Their relative outsiderdom was partly due to plain oddity, Be-Bop being a very British amalgam of mannered glam a la Cockney Rebel, post-Tommy classic rock, the proto post punk of Eno’s Taking Tiger Mountain By Strategy and the avant-prog of King Crimson’s Red. As such a DNA might denote, Be-Bop’s other problem was poor timing: not only debuting with the Ziggy-esque Axe Victim at the tail-end of glam in late 1974 but unveiling Bill Nelson’s guitar virtuosity just as prog’s popular credibility was curdling.

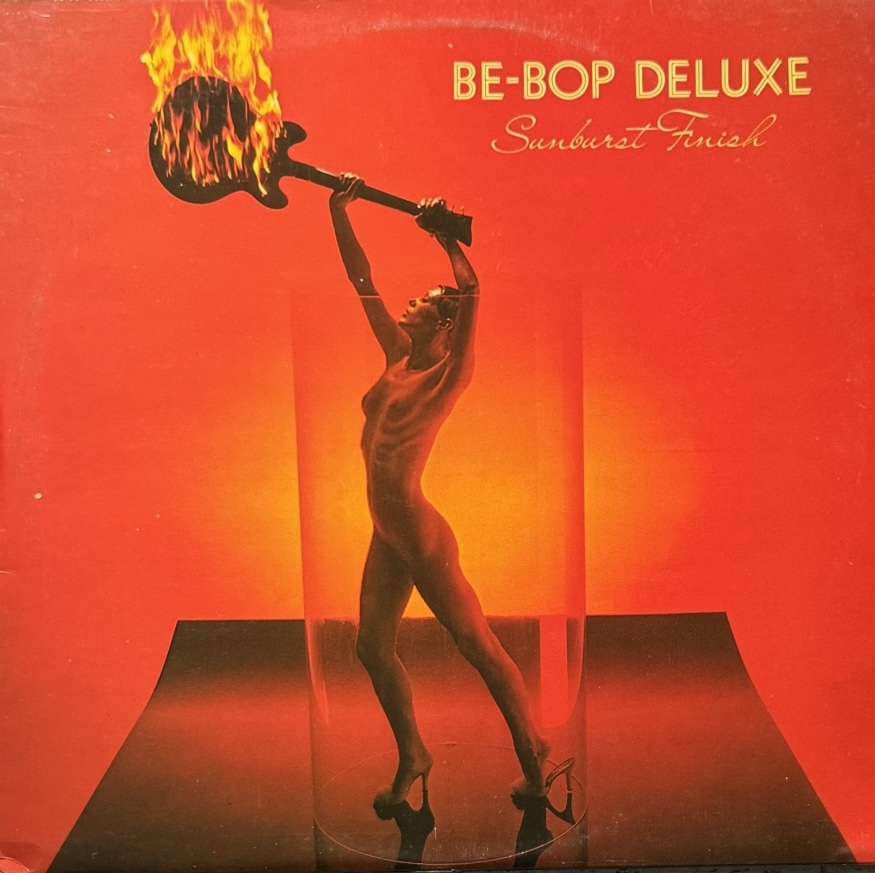

Be-Bop Deluxe’s unique charms were always recognised by other musicians, however, and despite biting on Bowie, the Thin White Duke would filch Sunburst Finish keyboardist Andy Clark for 1980’s Scary Monsters. In tandem, post punk acts like Invisible Girls, The Skids, A Flock Of Seagulls, David Sylvian and Gary Numan all hired Nelson as either producer or guitarist. For the new wave generation coming of age in the mid-70s, with glam worn out, Bowie and Roxy souled out and prog bloated out, Be-Bop Deluxe represented a rare art-rock beacon in an arena- and soft-rock wasteland. Not that you’d guess this from Sunburst Finish’s bozo Spinal Tap cover, which is as ‘of its time’ as their taste-free stage outfits.

Each of Be-Bop’s five albums are worthy of investigation – with Axe Victim a glorious glam artefact – but Sunburst Finish, their third, is their most consistent and coherent. It’s also, in the world that ABBA’s prog-pop ‘S.O.S’ had opened six months prior, their poppiest, becoming the first Be-Bop album to chart off the back of their sole hit, the reggaefied synth-rock whimsy of ‘Ships In The Night’. This single captures all that’s both awkward and attractive about Be-Bop Deluxe. The track’s lustrous melody and lyrical last hurrah for countercultural love – “without love” we’re “selling our souls down the river” – are less complemented than complicated by Be-Bop’s restless inventiveness. Clark’s keyboard solo manages to turn that most soft rock of instruments, the Rhodes electric piano, into art jazz. Nelson’s brother Ian’s wheezy saxophone solo adds a village hall amateurishness that verges on undermining, but ends up endearing – a precursor to post punk use of the sax in everything from X-Ray Spex to the Banshees. And there’s little better in music released in this period than ‘Ships In The Night’s shimmering synth/guitar intro.

The synth quacks that pepper ‘Ships’ are typical of the delightful sonic details that bedeck the album – the tabla and wah-wah hits ushering in ‘Life In The Air Age’; a magical waft of koto after the invocation of “substances of old Japan” on ‘Blazing Apostles’; a whistled snatch of jazz standard ‘Memories Of You’ on ‘Crystal Gazing’. Beautifully orchestrated by Cockney Rebel arranger and future Kate Bush producer Andrew Powell, ‘Crystal Gazing’ may be a smidge too close to Mott’s ‘All the Young Dudes’ in parts but it still sounds stunning, as does the album throughout. Produced at Abbey Road by Nelson and John Leckie, Sunburst Finish was a production debut for both, although Leckie had already sound engineered for everyone from The Beatles to Pink Floyd, Cockney Rebel to Mott the Hoople. With Sunburst providing further evidence that the 70s were the golden age of sound, the album intermittently corrects the only flaw in the period’s production – a notoriously muffled snare sound. ‘Life In The Air Age’ here has a drum-sound to die for – boasting a perfect breakbeat from 3:34 to the close – soon to be sidelined by the sonic attenuation of punk. While there’s no denying the sound of kids let loose in the proverbial candy shop on Sunburst Finish, the album’s sonic indulgence emits not elitist snobbery but, rather, an inclusive ecstasy.

One of the stereotypes of the 70s is that they were grim, yet the New Economics Foundation’s Measure of Domestic Progress research revealed that 1976 was, in fact, the peak year of British national happiness, suggesting the decade wasn’t only a sonic golden age, but a social golden age as well. If mid-70s music didn’t hit the ecstatic peaks of glam or ghetto soul, the popularity of sumptuously appointed soft rock from The Eagles to ELO was indicative of a contentment underlined by the period’s recurring hymns to domestic bliss from The Carpenters’ ‘Only Yesterday’ to Bryan Ferry’s ‘Let’s Stick Together’.

The elegantly accoutred ‘Heavenly Homes’ is Be-Bop’s take on the domestic contentment song, and is, unsurprisingly, the least post punk-sounding number here, an elegant pop prog ballad that recalls Leckie and Abbey Road clients, Pink Floyd. If the long-tressed Andy Clark looked more like a Floyd alum than a proto-post punker, that virtuosity meant he could match Nelson’s fluidity note-for-note, and here decorative piano-detailing perfectly complements luxurious guitar flourishes. The fact that the period’s popular contentment was about to be disrupted by economic (and political) retreat from the post-war settlement, is presciently captured by ‘Heavenly Homes’. “Heavenly homes are hard to find” muses Nelson on the closing lines, “Heavenly thoughts in heavenly minds/ Are not the world’s design”. There’s a sense, here, and on the album as a whole, of last-minute indulgence alongside adroit indemnities against future austerity.

This dual move means that while Nelson doesn’t quite indulge the guitar pyrotechnics of previous albums – ‘Ships In The Night’ and ‘Crystal Gazing’ are the first Be-Bop tracks without guitar solos –Sunburst Finish is still an axe-botherer’s delight. The yearning ballad ‘Crying To The Sky’ boasts not one but two stunning solos. Saturated in feedback and scintillated with reverb, Nelson’s guitar, like so much guitar-work avowedly inspired by Hendrix, sounds far more like its author than its inspiration: indeed, it’s close to Nelson’s best playing. While Nelson’s songs can sometimes seem like scaffolding for solos, the intricate chords of ‘Crying To The Sky’ and its meteoric, reverse-echoed vocals combine with the howling, reverberating guitar and echo-drenched tape storm-effects to create something genuinely, kinetically elemental.

As ever with Be-Bop Deluxe, Sunburst Finish’s tracks absolutely teem with ideas, but now all packed into pop-song length. The sole temporally and melodically unwieldy track from the sessions, ‘Shine’ was stuck on the B-side of ‘Ships’ to the undoubted bemusement of teenage pop-pickers. Yet even ‘pop’ Be-Bop is a heady experience. Opener ‘Fair Exchange’ starts like a Fripp ambient track, chucks in a Chuck Berry riff under the chorus, then see-saws between that rock & roll chorus and a Euro cabaret piano-ballad verse, before a prog instrumental passage becomes a Thin Lizzy/Big Country folk reel for electric guitar and synthesizer. This attention-deficit approach is playful rather than pompous, however. “Just give me your money, and I’ll give you my pain” quips Nelson: “Just give me your body and I’ll give you my brain”, with both options representing a ‘Fair Exchange’. There’s a lovely performance of the track on Old Grey Whistle Test, where bassist Charlie Tumahai gigglingly lands Nelson a smacker after they share a mic to sing “your boyfriend Stan is a dirty, flirty man”. Shield your eyes for the outfits though.

Cabaret is a recurring motif for Be-Bop Deluxe, who, like Roxy Music (on ‘Song for Europe’), David Bowie (on ‘Time’), John Cale (throughout Paris 1919) and Cockney Rebel (on ‘Sebastian’), pioneered the early 80s European turn in British music. The fact that UK membership of what was then the European Economic Community had been unanimously ratified in a referendum in summer 75 was hardly coincidental. While the charging opening section of ‘Sleep That Burns’ is overtly Who-inspired (sharing ‘Baba O’Riley’s chord sequence), it then shifts to a Parisian cabaret section, set to a tango rhythm. As if that weren’t eclecticism enough, it then switches to a backwards guitar-solo dream-sequence that recalls all those psychedelic sleep songs from ‘I’m Only Sleeping’ to ‘I Had too Much to Dream Last Night’, before somnambulantly drifting back to its galloping opening.

Virtually a continuation of the same song, ‘Beauty Secrets’ urges, “Bring on the cabaret, we can all have a laugh/I’ve made the Theatre of the Absurd at last.” Here again is that Be-Bop self-awareness, a meta-tendency, with the lines “Hand me my costume, please, won’t you pass me my mask? /I have appointments that I must keep with my past” harking back to Be-Bop’s fumbled glam beginnings. This leads to the acknowledgement that, “these beauty secrets that I’ve kept so long/Have slightly faded like my old blue jeans”, itemising the way glam followed the hippiedom it replaced into cultural obsolescence. In this context it becomes clear that Be-Bop’s self-awareness was another insurance strategy.

This makes the presence of ‘Like An Old Blues’ initially an anomaly, given its use of blues scales, its lurch into ungainly boogie rhythm, and grating mouth-harp solo. Yet if that ‘old’ in the title wasn’t clue enough, Nelson’s invocation of “boogie!” hips the listener to the track being another Be-Bop meta-song. The chorus deploys “like an old blues you never use/going out of style, and it’s not worthwhile” as a metaphor for a relationship. But as the music keeps stretching out into a blues-free Eurozone (accentuated by another grandiose Powell orchestration), it’s also a commentary on Be-Bop’s – and art rock’s – position in a liminal musical space somewhere between Europe and America, with Europe currently the dominant force.

Taking the same transatlantic journey, closer ‘Blazing Apostles’ functions in perfect circularity with the opening ‘Fair Exchange’. Kicking off as an Eddie Cochran riff, it launches into a glammy, declamatory verse over a variant on the Peter Gunn theme, then peaks in a synth-shimmering Europop chorus. Boasting a killer guitar sound and an aggression rare in mid-70s rock, the result is proto-punk, or given its intricacy, proto post punk. It also pre-empts post punk’s po-faced corporate satire from Devo to John Foxx to Heaven 17, with the irony at this point still intact: “if you are needing an angel of light/why don’t you give us a call? … Just keep up with the payments”. Be-Bop would suit-up for Modern Music later in 1976, just before punk’s first missives from The Damned, Vibrators and Sex Pistols gave full vent to the malaise hinted on ‘Heavenly Homes’. Despite Clark defying the corporate hair-cutting memo, he’d be Be-Bop’s sole survivor when Nelson created the more overtly new-wave Red Noise in 1978. Leckie would go on to produce seminal post-punk records by Magazine, XTC, Simple Minds and The Fall. Sunburst Finish then is a key staging post in the journey from art-rock to post punk.