Fifteen years ago I started a thread on a discussion board I’ve long been on with these words:

"Aphex Twin’s Selected Ambient Works Volume II is ten years old. And this, more than Kurt Cobain being dead, gives me a sense of the passage of a decade. In a far more positive way too. I listened to the album for the first time in a long while the other day, and I realized how utterly fantastic it was all over again. Scrape away all the dull as ditchwater clot accrued to it over the years thanks to so many indifferent IDM releases, and it’s all the more lovely to appreciate, a glorious one-off from him in that nothing (much) was spiked with the humor or freneticism or any of that from elsewhere."

And ten years on I am listening to it again – for the first time in a long while, though not, I think (I think?) the first time since ten years back. Kurt Cobain doesn’t come to mind as a comparison point or a reference for time in the slightest now – I forgot I even considered that when I wrote that comment. It’s not that the two were ever associated to my knowledge, beyond the fact that a cover story in Melody Maker was still the central story, but the cover itself either went towards covering Cobain’s near-death in Italy or the final grim end in Seattle. History is often nothing more than accidents.

SAWII seems like an accident, something assembled cryptically and then released on no sense of schedule or timetable beyond whim. Its very title forces consideration of the previous collection which had surfaced two years previously, but barely seems to have any relation to it. It was created in power plants, it was done via lucid dreaming, the titles are the photos, are the guesses. This all might apply if you believe what Richard D James has said – and as he’s said plenty of times, there’s no reason to, happily engaging everyone with straight-faced humor and tall tales just because it amuses him, a grand plan that does or doesn’t actually exist and doesn’t need to.

A new entry in the 33 ⅓ book series by Marc Weidenbaum does deeper delving into the album than I can even attempt here, so I encourage you to consider that if you want something more rigorous, as well as this 2012 interview preparatory to its release, where Weidenbaum notes something key I’ve turned over a few times as well: "I want to probe the one thing that is pervasively understood about this record, the "fact" that is synonymous with Selected Ambient Works Volume II, which is the idea that it has no beats. This is commonly asserted about it, that it has no rhythmic content. I think this is, simply, false. Much of the album has rhythmic content, even a consistent beat, if not two or more beats working against yet in concert with each other. I want to explore the perceived tension between ambient sound and rhythm."

Weidenbaum hits this point that’s easy to forget, yet is terribly clear — there is rhythm throughout the album, actual beats at points as noted, but more often creating the kind of intertwined obsessive exploration that seemed – at least to me at the time – to be matched solely by the work Robert Hampson was doing more and more via Main. Where that duo, and eventually solo act, had as its sometime motto ‘drumless space’, there was never absence of rhythms, the space was disciplined, shaped and mutated constantly, an ever shifting nervousness. James had his own approach, and comparatively SAWII is more recognisably a world of ‘songs’, shorter in length, focused on key fragments or elements that never departed. But the further you went in, the further it wasn’t drumless space indeed – it was often just space. A black cold space, seemingly antithetical to the white cold space of the sleeves, but just as alien, and just as unnerving.

The appeal of the album lies in that sense of disentangled fragments assembled and presented without further to do. There was plenty around the album, of course, that was the whole point: Aphex Twin as figure/marker/concept was already well established in certain circles. From the vantage point of two decades I can see a little more clearly (a little) how acts can be framed and marketed; how a fairly handsome long-haired white guy with a gift of gab and a sense of humor could easily become a focal point even among a blizzard of singles and collections that even then were starting to emerge rapidly. (Could be wrong, but I’m sure the first time I actually heard anything of his was a year earlier, and that album – Surfing On Sine Waves – was released under the name of Polygon Window.) That the Aphex Twin would prove to be a reasonable selling point in Melody Maker, my sole regular lifeline to UK press thought, advertising and reaction, makes sense. He wasn’t the only one covered in it by a mile, but given the stop-start attempt by the paper to incorporate dance coverage in general throughout the early 90s, he often stood out; the more so because, for all the raves he played and anthems before and since he’d have a hand in, he seemed just arty enough, just weird enough, just enough like a lot of the presumed student-age audience of the paper. And he was evidently, erm, intelligent.

THAT word. Those three words, actually, "Intelligent Dance Music". I mentioned IDM earlier because that’s around when I heard the term and took it to be something vaguely meaningful, more fool me. I even took the trouble to subscribe to an online mailing list dedicated to such stuff, and I still remember one of the first things I saw on there were a series of complaints about how bad the vinyl pressing of SAWII allegedly was, one of my first tastes in how the belief that everything’s better on vinyl seems to just increase blood pressure. As with any canon being assembled by chance, the list’s field of discussion was a bit of a broad remit – on first blush it could be essentially seen as Warp and/or Rephlex, but then you’d get other people brought in, not to mention earlier figures still working away regardless of classification (Coil was one instance, a connection that only grew stronger with time, especially when Autechre started mutating soon after). But the acts all got stuck with the term one way or another, plus they often had to deal with a resulting snobbism and not-even-very cryptoracist assumptions lurking behind the term – "Oh yeah, we’re INTELLIGENT, not like, um, you know, those people… but maybe we could like jungle if we call it drum and bass, right?" A broad brush, but again, it’s not like that wasn’t often there, in some form. The slew of albums from all around that did come with that tag preapproved from a variety of sources ranged wildly, as with any putative genre grouping, and plenty of them carved their own bizarre and wonderful avant-garde paths, but oh, the sludge, the SLUDGE, especially as the decade went on. It almost made nth-generation grunge releases seem appealing. (I said almost.)

Yet for all that he got into a snark war with Stockhausen and later had Philip Glass remix him and so forth, James never seemed into playing any one particular role when multiple ones could exist. Seen from twenty years on, to restate the start a touch, the singularity of something like SAWII in James’s career seems both necessary and understandable; yet another indulgence in an approach, albeit one that has and continues to resonate, dig deep. Seen at the time, this could as easily have just have been his ‘new direction,’ where things would go from there in his career. Maybe there would be a third volume, a fourth, things would get even quieter than before, not that the first volume was some noisefest to start with. Maybe he wouldn’t care about IDM but he could have put out releases to be filed with another marketing term, and nothing would be seen again except one ambient techno collection after another. After another. (That same year in America, a ‘missing’ track, "Stone in Focus," which was left off the CD version of the album, turned up on another CD, assembled for the US market by EMI offshoot Astralwerks, called Excursions In Ambience – The Third Dimension, and while it’s not a half-bad grab-all of a comp, the cover is as generically bad as you might guess.)

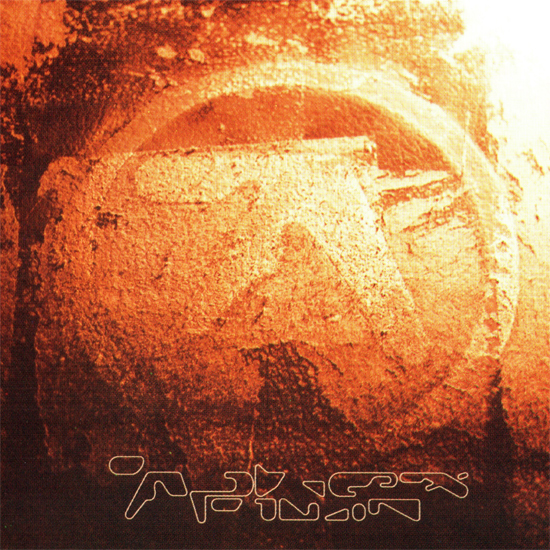

But instead of fractal oceans and the like, there’s something more. The logo from earlier releases, half alphabetic, half hieroglyphic, 70s technological and then something else, could have just been reused again. Instead, burnished, dusted, as if just pried up from somewhere, it feels like a capstone to an archive from a Neal Stephenson novel, some sort of lingering memory hidden away and marked in case of potential or inevitable disaster. But perhaps it’s more like science fiction like Shane Carruth’s work is science fiction, a viewing of the mundane and seemingly immediate through different eyes. The lack of titles, the bare minimum of liner notes provided more for legal reasons than anything, and similarly feeling like they’ve been found scratched on a brass plate, it’s more prog rock than most prog rock could ever hope to aim for, in plenty of ways.

The first song I heard was one that had already been picked out in a review and is perhaps the prettiest, most conventional song on the album, ‘Rhubarb’, a feeling of high church on a distant peak. If the ghost of figures like Eno inevitably hangs over anything that could be called ambient – much less a term that at the time seemed to only be a bad joke of a hangover, new age – what James did here, like others elsewhere, was to translate the impulse and suggest other ways to work with it. Miles away from ‘Digideridoo’, a whole universe away from ‘Windowlicker’ or ‘Girl/Boy’, it’s as close to ambience as gentle balm as one could want, but even then it’s not really that, enveloping in its stripped down beauty but so stately, so focused, warm and cold at the same time. If I had to pick a song, it would be that, but it’s not just that – there’s too much going on elsewhere.

Once, I tried to describe how the album feels this way:

"…so it goes, strange coos of babies, subliminal melodies, things taken out of context and reassembled in contexts which don’t quite sound out of place or distinctly wrong, but are still just that little bit wrong, and just that little more than music to fall to sleep by. Two and a half hours of it and I couldn’t remove a single track, really, the way it’s all put together and how it sounds. By the time it does finally conclude with the bottomless cold creep of the final track, an echoed percussion sound almost like a rippling raindrop and floating musical colors out of the wrong sort of space, things aren’t quite what they seemed as when we started, and clearly we’re not in Kansas anymore."

Glib, but I’d say not inaccurate. I’d like to know exactly what I did think of it all when I first heard the album, whether it took me more by surprise than I realised. But it’s that balance it does maintain – between accessibility and the unusual, the familiar and the quietly, slowly terrifying – which makes it work still. It doesn’t rampage but it doesn’t cossett, and whatever internal logic drove its creation and sequencing – the latter still vitally important, it does need to be heard in its full form – results in something that’s always like a pleasurable puzzle to solve, rather than something to frown at and eventually discard. I wonder idly how British – not necessarily English – an album it is. Could it have been done anywhere else, by anyone else? I hinted at Oz in my earlier take, a classically American setting. But would or could this album have existed in a different world from Dr. Who memories and JG Ballard nightmares? Others might have better senses of the subcurrents that can be brought to bear upon an album that seems to welcome reader response theory – maybe you can hear what you want to within it, unclear visions, strange frequencies. In its seeming simplicities, space allows expansion of interpretation.

In late 1994, the Japanese anime series Macross Plus debuted. Set in a future time, in its first episode there’s a moment when a rotating video ad at a bus stop promises the release of AFX’s Selected Ambient Works Vol. 23 2038-2040, complete with that first ambient collection logo. There’s still no guarantee of that happening, but if we had never been given this second collection, I don’t think any SF or futurist creator beyond James himself could ever have dreamed of it.