On Talkie Walkie, Air’s third album proper, there’s an instrumental track called ‘Mike Mills’. Featuring a metronomic click and a swirling, intricate Bachian counterpoint that dazzles in an understated way, it’s a titular dedication not to the once world famous REM bassist and songwriter of the same name, but rather the polymath who was all but the third member of Air in the early days. The vision of Mike Mills, graphic designer, video maker and later movie director, helped propel Air not only into the stratosphere, but also into the more rarefied Anglosphere – a place where French bands didn’t really belong in those days.

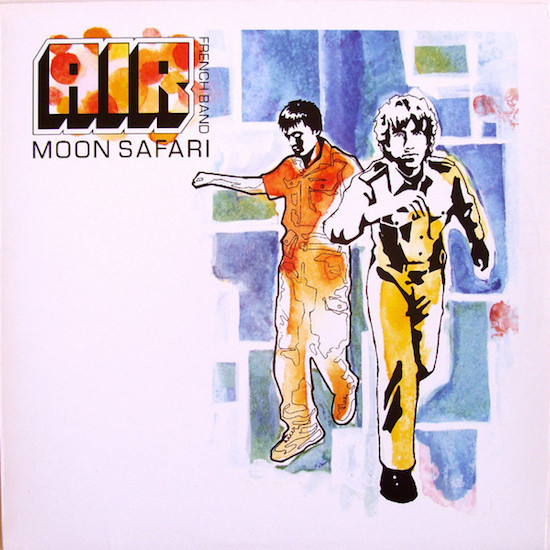

You can see how vital Mill’s input was on the Moon Safari cover art. Firstly you’re struck by the two retro colouring book figures representing Nicolas Godin and Jean-Benoît Dunckel, and then the Air logo with Moon Safari written underneath (Air is an acronym of “Amour, Imagination, Rêve” apparently). And then finally, almost subliminally, you notice the words “French band” in smaller type vertical to the main logo. Had this been put there ironically? Was French band really considered an oxymoron at that point? Or was it warning the listener that they may experience waves of exoticism within? Or perhaps conversely it was like the advert that was all over France a few years ago for a well-known British digestive biscuit that ran with the strapline: “c’est Anglais, mais c’est bon”. Internet use hadn’t proliferated enough for there to be concerns about finding Air in a search engine, even if you almost certainly have to write “Air French band” to achieve pertinent results nowadays.

The symbiosis of graphic design and French music was stronger than it had ever been in 1998, with many of the groups associated with the French touch now using available technology to cut and paste strong, edgy sleeve designs on a shoestring. Being on a major label, Air were lucky enough to be able to hire someone as talented as Mills for their artwork and videos and bring something exceptional to the table. Timing is everything, and arriving at the tail end of an exhausted Britpop movement in the UK – which had been musically protectionist and derivative – Air were exotic while maintaining enough elements of classic rock propagated by the likes of Electric Light Orchestra to appeal to a rock-orientated crowd. While they didn’t exactly fit in anywhere, they did what so few French bands had hitherto done, by breaking through to the UK market.

It may come as a surprise that Air have never entirely fitted in at home. Regarded as Parisians by everyone but Parisians, they’re actually from Versailles, an Yvelines commune made up of around 100,000 people 10 miles southwest of Paris. Indeed they’re the biggest thing to come out of la ville du Roi Soleil since the League of Nations, though that’s not saying a lot. Furthermore, they’re regarded by many as proponents of the French touch, though they again sat on the peripheries, too downtempo to really be a part of the scene, more easy listening vanguards of the chill out room than doyens of the dancefloor. This inability to belong or be compartmentalised was reflected in the duo’s chart placing at home: their debut album peaked at no.21 in the French album charts, and while it has sold around 2,000,000 copies to date, only 100,000 of those sales were in France. Part of the reason may be the collaboration with Beth Hirsch on two tracks, an American singer Godin met near his home in the 18th arrondissement who added a plaintive sophisti-pop element on ‘All I Need’ and ‘You Make It Easy’ that he describes as being like a “space-age Carpenters”.

“We had English singing so it was perceived in France as something more Britannic,” his bandmate J.B. told Loud And Quiet in 2016. The indifference was so pervading outside of the capital city that they claim it was difficult to tour the record in the rest of France at the time.

That’s only half the story though, because while Air failed to fully connect with their home audience, they chimed with everyone else. Moon Safari has to date gone double platinum in the UK, shifting a quarter of a million in Germany and nearly 400,000 in the US. And while the heavily disguised Daft Punk had become famous thanks to 1997’s ‘Da Funk’ (and it’s video, directed by Spike Jonze) and the ‘Around The World’ single (video directed by Michel Gondry – also from Versailles, incidentally), Air, with their visages free for all to behold, would become the most recognisable French pop stars since Vanessa Paradis. What’s more, Moon Safari or the big single ‘Sexy Boy’, were not regarded as seasonal novelty records wafting in on a warm front and outstaying their welcome like a fungal infection from a holiday romance. “Before Daft Punk and us, French pop was synonymous with Sacha Distel. I hated it,” Nicolas Godin told the Guardian. “But electronic music meant you could make cool music without being a rocker.” The oscillating bassline is immediately recognisable, the ambient textures unmistakable and the lysergic rush at the beginning of the phrases on ‘Sexy Boy’ make for an arresting listen. Lyrically, the knowingly tongue-in-cheek appreciation of masculinity was playful and subversive, while musically it was the well crafted simplicity that made it such an unusual single in 1998. “Ever since I was a child, I’d dreamed of making a classic album – and I actually did,” Godin told the Guardian. “The night we did ‘Sexy Boy’, I knew my life would change.”

The more metropolitan and hip Daft Punk might have ruled MTV at the time, but Air found themselves at home on rival channel VH1, watched by viewers who’d regard themselves as discerning rock fans. The album also fared favourably with the rock press, topping end of year polls of both Select and style mag The Face. It is ostensibly an electronic record, but there is a rock sensibility hiding within its layers. Much of that comes from the utilisation throughout of a Hofner bass a la Paul McCartney, played by Godin through a guitar amp to give it a more melodic higher end. To hear the opening few moments of ‘La Femme d’argent’ all over again is to be spiritually transported back 20 years; Moon Safari embodies the sounds of fin-de-siecle downtempo pop better than most other records, but what’s most surprising listening to that track again is how they got away with presenting a languorous jazz-inflected jam session with merely a strong basshook and some atmospheric banks of keyboard as the album’s opener. The bongos are a surprise too, but if it works it works.

Conditions wise, a revival in loungecore, where kitsch was cool and Burt Bacharach was king again, also contributed to their acceptance on these shores. If – as we’ve said before – timing is everything, then they arrived when easy listening was being enjoyed ironically, and not so ironically, and music buyers were suddenly scrambling for previously discarded vinyl in charity shops in search of rare grooves. On the peripheries you had artists as diverse as Jimi Tenor and Count Indigo tapping into big band nostalgia in different ways, while Faith No More were covering ‘This Guy’s In Love With You’ and Mike Flowers Pop were challenging for the Christmas no.1 with a bossa nova version of ‘Wonderwall’. The proliferation of latin jazz, the going overground of acid jazz and the explosion of the Bristol sound all helped make the conditions right for Air. Then of course there were Anglo-French noiseniks like Stereolab wearing their easy listening influences with panache. The generic British attitude to French pop at the time, sitting somewhere on a spectrum between ignorance and prejudice, would have been put to the test when Laetitia Sadier et al performed a blistering ‘French Disko’ as guests on Channel 4’s The Word in 1993. To suggest their influence paved the way for Air would be overstating it, but for those who had dismissed French pop as gimmicky, gauche or replete with gimcrackery would have been forced to reconsider.

Moon Safari is a sophisticated, ambient pop album, even if some of the ideas behind the songs weren’t exactly urbane (‘Kelly Watch The Stars’ was inspired by Kelly Garrett from Charlie’s Angels and in honour of Jaclyn Smith’s pulchritude). So did Air make the world take French pop seriously? If the answer isn’t strictly yes then their help in galvanising a growing backlash against long entrenched attitudes to music made across the channel can’t be understated. They arrived in the right place at the right time, a marriage of music and design that chimed with a cross section of demographics in a way that was entirely serendipitous and impossible to preempt. Suddenly French band was no longer regarded as a paradox, the airwaves were full of French disco (such as Stardust’s ‘Music Sounds Better with You’) and Madonna was picking up and working with unknown producers like Mirwais, who apparently came to her attention with a demo sent to her Maverick label. It’s peculiar to think France was still artistically as remote as a visit to the moon in the mid-90s, but musical voyages between the two – thanks to the likes of Air and Daft Punk – have become as commonplace as trips by Eurostar ever since.