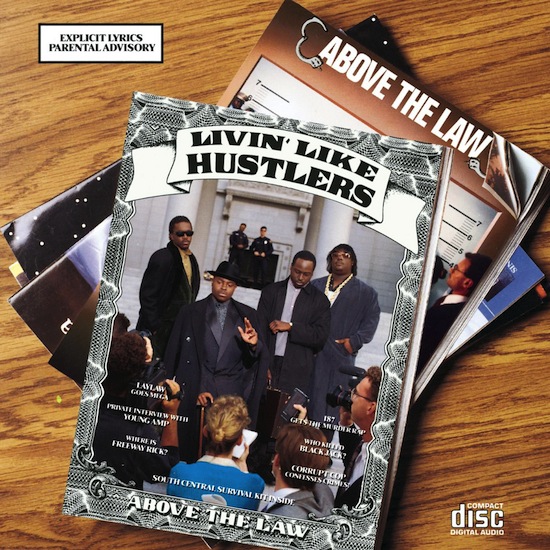

Of course, everything’s subjective: but – to these ears – there have been very few true classics to emerge from the scene/style/sub-genre known as "gangsta rap". As I’ve discussed in this series before, these are records where significant constituent components make them hard to love unequivocally. Some of this, of course, is as it should be: music that exists – at least before the style became commodified and artists began to include gangsta tropes because they thought it would help records otherwise lacking in them to sell – to shine a light on the lives of a hitherto ignored and increasingly criminal underclass aren’t going to be full of the joys of spring. But even when acknowledging that from the outset, the examples of gangsta albums that leaven their sociopathy with sufficient insight, musicality and originality of thought to rise above the fundamentally depressing is tiny. And indeed, if one sets the work of the Ices T and Cube to one side – and perhaps even if one doesn’t – the numbers of records left that feel worthy of cherishing can be counted on the fingers of one hand. One of those records – and in this writer’s estimation, the best of them by a significant margin – is the debut from Above The Law. Not just one of the most influential if least-known hip hop records, Livin’ Like Hustlers may well be gangsta rap’s finest hour.

The group – Cold 187um, Go Mack, The Illustrator K.MG, producer/manager LayLaw and DJ Total K-Oss – hailed from the Pomona district of east Los Angeles and were among the first signings to the Ruthless label made by NWA instigator Eazy-E. The second of their eight albums – Black Mafia Life – contained a stellar guest spot by a still-up-and-coming 2Pac. They had completed quite a bit of work on a ninth when K.MG died in 2012. In a world soon overflowing with plastic gangsters and wannabes in braids and Carhart, they walked it like they talked it: in one passage of label co-owner and NWA manager Jerry Heller’s hugely entertaining 2006 autobiography, Ruthless – A Memoir, he tells a story of how a certain NWA member made the mistake of dissing ATL in an interview – backstage at a subsequent gig, Cold 187um handed out a beatdown. After some time had passed and an apology was made, the same member turned up again, expecting that past indiscretions would have been forgiven and forgotten. He got his ass handed to him a second time.

That Above The Law’s name is not more often found on the genre’s greatest-of-all-time lists remains a surprise, given that longevity, and the particular excellence of their debut. Yet history also seems to have failed to recognise the Ruthless set-up for the pivotally important business concept that it was. In their own way, Eazy and Heller established a means of bending the record industry to their will that others later built on and refined. Both Parrish Smith and Rza have identified Parliament-Funkadelic as being the key influence on the way first EPMD and then the Wu-Tang Clan sought to develop and market artists from within their extended families; but NWA and Ruthless did it too, and started doing it first. The label was established to release NWA records, but Eazy’s solo album was a natural step once Straight Outta Compton had made the group’s name. With Dre and Yella as in-house producers, other acts benefitted from the music-making elements as Jerry and Eazy sought to turn Ruthless into a foul-mouthed Motown.

Projects were worked on serially, with NWA members guesting, to help ensure sales to fans of the label’s biggest act. Heller, a music-business veteran who had cut his teeth working as a west-coast booking agent for rock and pop superstars such as Elton John and Marvin Gaye, knew that each record would stand a better chance in the marketplace if the independent Ruthless struck a number of distribution deals with different major and indie labels, and could minimise the chances of an overworked promotion team getting overwhelmed with new product. Thus the "core" NWA/Eazy releases came out on Ruthless via Priority; other artists were on Ruthless/Atlantic; and Above The Law came out on Ruthless via a hook-up with the Columbia imprint Epic. Each label was effectively forced to compete with the other – with no A&R department willing to go in to a marketing meeting and be forced to admit that they had not picked up the biggest Ruthless act.

The strategy worked like a dream. Critics and fans tend to look back on the first round of Wu-Tang solo releases as a high-water mark for this mode of making rap records, but of the equivalent chapter in the NWA family catalogue – Straight Outta Compton, Eazy Duz It, JJ Fad’s Supersonic, and debuts from The D.O.C., Dre’s wife, Michel’le, Above The Law and white female rapper Tairrie B – only the latter two failed to sell at least a million copies. (Several references online claim that ATL’s first two albums went platinum, but the group do not appear in the RIAA’s searchable database of gold and platinum certifications.) The D.O.C. would have become a huge and enduring star had he not lost his voice following a car crash on his way home from shooting his first videos; Michel’le might have received the credit she deserves for minting the R&B/hip hop crossover three years before Puffy and Mary J Blige came on the scene had her and Dre made another album together; and, according to Heller, Above The Law "would have been NWA if NWA hadn’t existed."

That’s not mere hyperbole on his part. Livin’ Like Hustlers is a magnificent record – easily the best album to emerge from the LA hip hop scene by that time – and while the rappers may not quite have developed the skills as innovative stylists that characterised the best work of Cube or Snoop, the performances and poetics throughout are effective and compelling. More encouraging – though this is to damn the record with faint praise – the objectification of women and casual, ignorant sexism is far less frequent than in other gangsta albums, and consequently much less of a barrier to accessing the album’s lyrical successes (principally some nuanced humour, splashes of well-drawn and well-observed characterisation and storytelling, and a couple of examples of socio-political critique which are unusually well executed and thorough in their conception). The worst sexism on the record comes in the closing track, ‘The Last Song’, and is delivered not by one of the group but by Eazy-E – and even there, the verse is so obviously a self-parody that it’s hard to take any of it particularly seriously. Admittedly, this is a bit like arguing that a window is only slightly broken, or that the soup contains only a tiny bit too much salt – the damage, clearly, is done regardless, even if the degree by which it was applied is comparatively minor. And the absence of a female character anywhere in the lyrics who occupies any kind of positive role rankles. Still: Above The Law never come across like they think treating women badly is a shrewd marketing move, which automatically makes them appear, if some way short of card-carrying feminists, than at least less misogynist than their peers.

The other element of nuance that doesn’t excuse but may partially help explain the "bitch"/"ho" crap feeds in to what seems in retrospect to be the album’s most long-lasting and far-reaching impact. The pimp may well have been a mainstream pop-culture archetype since at least the time Starsky & Hutch became a worldwide hit, and the "player"/"hustler" was probably established enough a trope of the entertainment media from the time of The Sting and understood more broadly since the early 1940s, and the publication of David Maurer’s The Big Con. Other ingredients of the persona constructed here by ATL probably date back to the 19th century, and to individuals like Lee Shelton, the St Louis pimp and gangster who was part of a group of high-profile, high-living criminals who styled themselves "Macks", and who, following his 1895 murder of a man after an argument over the theft of a hat, inspired the folk/blues song ‘Stagolee’. But it’s on this album where the character of a high-living, sharp-suited, smooth criminal with a bent for ruthless violence and a lifestyle funded at least in part from pimping enters the hip hop lexicon for the first time. It would be five years before Jay-Z took the concept as the basis of his image and lyrical persona on his Reasonable Doubt debut. And what’s striking is how fully formed the idea is here.

What’s also notable – and has become the source of some controversy over the years – is how this mack/hustler character sketch is married to music that consciously echoes, samples and interpolates smooth soul-funk sounds of the early 1970s. Up to this point, the dominant mode in hip hop production had been the dirty, dust-encrusted, almost punkish drum cracks of the James Brown school of late ’60s funk. Other artists had introduced some of P-Funk’s mellifluous symphonics but it was always the harder sounds that hip-hop producers tried to build their beats out of. Not here. On at least half of this album, the beats are constructed from the smoother end of the soul canon, from the kind of tracks well suited to blasting from the stereo of a low-rider Cadillac with the top down while cruising the Southland in the summer sun. This might not seem that big of a deal today, but that’s because, almost three years later, one of the people involved in making Livin’ Like Hustlers took that template and turned it into gangsta rap’s biggest hit album, setting a new standard others would rush to copy. The creation of "g-funk" has been credited to Dre ever since The Chronic dropped at the end of 1992, but Cold 187um has occasionally broken cover to argue that many of what were hailed as Dre’s stylistic innovations were actually things he had taught the NWA producer during the making of this LP.

According to the credits on the sleeve, Livin’ Like Hustlers was "produced by Dr Dre, AtL and Laylaw", in that order. In an interview with HipHopDX published five years ago Cold 187 said the album was created by taking tracks he had worked on at home to Dre, who would then expand, clean up and enhance the sound. This suggests that the basic shape and sound of the song, and the identification and selection of the samples, was down to 187. Elsewhere, claims have been made that Dre produced two tracks of the album and the rest was the work of Cold 187.

The striking and unusual songwriting credits on Livin’ Like Hustlers offer some significant support to 187’s claim. It’s important to remember that sample clearance is a negotiation between the artists using the sample and the owner of the original music: how – even if – the sample is credited is up to the two parties, and there is no industry-wide standard anyone is forced to comply with. Generally, samples are acknowledged clearly and specifically in sleeve notes – if they’re acknowledged at all. But on this record, eight tracks have songwriter credits written in the format "Words by X, Music by Y" – where the music-writer credit is the writer of the primary records sampled. This gave rise to considerable confusion – which persists to this day, if the Wikipedia entry on the album is representative – over the notion that the second track, and second single, ‘Untouchable’, samples The Doors. The writer credit would suggest this is the truth – it reads "Words: Cold 187um, KM.G; Music: Quincy Jones, John Densmore, Robby Krieger, Ray Manzarek, Jim Morrison". Listeners ever since have scoured the song, trying to identify individual drum sounds or guitar notes that come from a psychedelic rock song. In fact, the credit is accurate but the song does not contain any note ever played by the LA band: instead, the sample is from jazz outfit Young-Holt Unlimited’s cover of ‘Light My Fire’. (The remix for the video is a completely different track, which Cold 187 says was Dre’s work.) A similar fool’s errand awaited anyone attempting to find the Isaac Hayes recording sampled here to create the monumental slouch of ‘Another Execution’ – the sample is actually from a live recording of ‘Do Your Thing’, by James Brown associate Lyn Collins: Hayes wrote it and released it on the Shaft soundtrack, but the version sampled here is not his recording of it.

Anyway: Dre gets a writer credit only on two tracks – the opening first single ‘Murder Rap’, which uses a sample from Quincy Jones’ Ironside theme to give a Public Enemy-style siren-strewn noisescape effect quite out of keeping with the rest of the album but very much de rigeur for late ’80s hardcore rap; and ‘The Last Song’, a track for which no sample source has as yet been identified, and which may well be entirely the work of the studio musicians Dre and 187 had roped in for the project – guitarist and bassist Mike "Crazy Neck" Sims and keyboard player Andre "LA Dre" Bolton. This may be nothing more than a coincidence – after all, there is no writer credit for a producer on the other eight songs; just the writers of the track(s) sampled – and could explain the claim made that Dre only worked on two songs. But it seems odd, if he helped in the actual structuring of the backing tracks and was involved in choosing samples, that he would not have wanted to be credited (and therefore paid) for his writing work on the remainder of the record. Conspicuously, there is no credit for him on the two songs which most strongly anticipate the Chronic sound – ‘Ballin” and ‘Flow On’ – though, again, to be fair to all concerned, the latter doesn’t even credit any of AtL for the lyics, with the entirety of the song’s publishing and writing credit going to Aaron Schroeder and Jerry Ragavoy, authors of Love Unlimited’s ‘Move Me No Mountain’ which the track is based on a sample from. (Again, sample-clearance deals being entirely down to the two parties reaching an agreement, it’s by no means unheard of for the author of a sampled song to demand 100 per cent of the new song’s songwriter royalties.) Observant listeners will note the mention in the lyrics to a potent strain of weed that was being called "chronic" – probably the first use of the word in that context to appear in a rap.

Beyond the paperwork, there’s clear audible differences between the first and last songs and the rest of the album. ‘Murder Rap’ is a series of layered samples that takes its cue from the PE/’Straight Outta Compton’ school of noisy, aggressive-sounding rap production, and ‘The Last Song’ feels very much like rappers getting busy over a band jam, with verses highlighted by musical references to previous hits (Dre’s verse gets the woodwind squeal used on the ‘Express Yourself’ remix and which also featured in the almost contemporaneous Happy Mondays ‘WFL’ dance mix; a guitar riff from ‘F— Tha Police’ is played during Ren’s verse). The rest of the record sticks to a format where a single, highly melodic, sample is played straight, with perhaps a minimal embellishment such as the overlayering of a single clean drum break to emphasise or firm up the beat, augmented with another, usually melodic, hook to form a chorus, and then rapped over. It’s an altogether more simple way of working than audiences weaned on It Takes a Nation of Millions… or Straight Outta Compton would have been used to hearing, and is very close indeed to the way Dre worked with samples from George Clinton or Leon Haywood a couple of years later.

The epitome of the style, and one of the finest tracks in rap history – a gem of simplicity, imagination, and peerless studio craft – is the side two opener, ‘Just Kickin’ Lyrics’. The beat comes from Joe Tex’s break staple ‘Papa Was Too’, and overlays a chunk of another already well-used classic, the Isaac Hayes track ‘Hyperbolicsyllabicsesquedalymistic’. This had been introduced to hip hop’s sonic lexicon by Public Enemy on ‘Black Steel In The Hour Of Chaos’, and would periodically reappear in a very similar form over the years (the finest example being on Cypress Hill producer DJ Muggs’ first solo LP, on the song ‘Puppet Master’, which featured raps by B-Real and, coincidentally, Dr Dre), but here a different part of the song is used – a section where Hayes is playing a repeated pair of single notes several octaves apart, while the bass line cycles beneath. Isolating and looping this section created a track that sounded instantly familiar to rap fans who’d heard PE but not the Hayes original, yet completely different to anything they’d come across before in hip hop. Moreover, the way the loop is produced, as if somehow the ATL crew had been given access to the Stax master tapes and were able to separate, isolate, polish and replace each instrument into the mix, ensures a rich and live-band feel – maybe this is one of the instances where the musicians were called on to re-play elements of the sample, though the sonic fidelity to the Hayes track suggests not. There are two fragments of Hayes’ vocal that float in and out, very occasionally – a murmured hum, and a snatch of a vocal ad lib ("I like it like that"), which underline that this is human music, not mechanical reproduction. The vocal – all three verses are by 187 – ends up as seasoning for a superlative sonic stew, a final garnish to a piece of musical creativity that is characterised by its innovative yet bare-bones approach.

"I think that 187 was a trend-setting producer," Jerry Heller told me in a 2006 interview. " I think he taught Dre many of the things Dre utilised on NWA records. I think Above The Law would have been an incredibly important group, except for two things. Number one, there was an NWA, and number two, Dre’s ego wouldn’t allow him to elevate Above The Law to the position of NWA. You know, Dre is a very non-confrontational person with an incredible work ethic. He’ll be in the studio until he can’t hear any more – he won’t get up from the board except to go to the bathroom. So this guy has a tremendous capacity. But I could never get him to go back and do a second Michel’le record – not that Michel’le had the importance of a Rakim, but I gotta tell ya, that if it wasn’t for Michel’le, there never would have been a Mary J Blige: R&B with hip hop tracks. We did a lot of trend-setting things, and I know that Eazy and I as businessmen would have loved to put out a second Michel’le record, because it would have sold 10 or 12 million copies. And I could never get him really to help Above The Law. Now, there was nothing ever said, there was nothing spoken: he always found other things to work on. But it was always my feeling that they could have been a very big group."

Heller went on to argue, of Dre, that "I think, as he became more and more alone – remember, he had Yella before, he had Eazy, he had Cube, and he had the Above The Law guys: he had other input – I think that as the weight of his empire got heavier on his shoulders he probably looked to other people for fresh ideas. And there’s nothing wrong with that – it’s part of the process – but, I mean, if you go back to all of that early stuff, that noise in the background, that classic NWA background sound of the screaming sirens, he took all that from Above The Law." There’s two ways of interpreting the latter part of this statement, and the one I took initially made me think Heller was mistaken: the sirens, the noise, that was in NWA from day one – Dre wanted to make Bomb Squad-style beats and Straight Outta Compton is him doing that: he even looped some of the same samples. On reflection, I think Heller probably was referring to the long, single-note analogue synth lines over slow, loping beats that only start to appear in Dre’s production on Efil4Zaggin, specifically in the single ‘Alwayz Into Somethin”, released the year after Livin’ Like Hustlers (even the between-albums, post-Cube stopgap, ‘100 Miles And Running’, retains an uptempo PE vibe) – and in that case he has a point.

There isn’t anything quite like that on this record, but ‘Ballin” is close, and the use of long, drawn-out tracks drenched in strings on ‘Flow On’ does head in that direction. Only those who were there really know what went on, but if we listen to the records in order and try to piece a history together based on analysing the evolution of the sound, a picture begins to emerge. At first, Dre built multi-sample, uptempo, hard-hitting and noisy beats, with sirens and sound effects adding drama over music that derived its atmosphere of anger and energy from its visceral and propulsive sense of momentum. This side of his beatmaking sensibility is audible in his collaboration with Cold 187um, on the tracks we know he was responsible for – ‘Murder Rap’ and the ‘Untouchable’ remix, which are very much in the NWA mould – but at the same time he was experimenting with creating lusher, more natural-sounding tracks using live musicians, which appears to have been the case with ‘The Last Song’. The clarity, the separation of the different instrumental elements, and the painstaking precision with which each track was made to sound bright, crisp and alive is also something that was there from the first time he was let loose in a proper studio and is clearly a signature part of his production style, even by 1990: 187 says as much when he describes how he took his home-produced tracks to Dre for them to be turned into blockbuster cuts. But the fascination with slower beats, often derived from soul tracks popular in low-rider culture, and their linkage with those high, piercing synth lines, which tend to inspire the musical equivalent of wanting to shield your eyes from bright, low sunshine – those don’t enter Dre’s work until after this album. Various unsubstantiated claims have been made that The Chronic was inspired by Dre’s discovery of "underground tapes": but if those tapes ever really existed, and were good enough to spark as careful and considered a musician into a fundamental change of direction, it’s odd that nobody has been able to identify them, and even more surprising that no artist responsible for making them has stepped forward to claim a share of the credit for inspiring a sound that went on to dominate global pop music for half a decade. On the balance of available evidence, a definitive verdict is going to be tough to call: but an objective observer applying Occam’s Razor would perhaps be minded to conclude that Dre first encountered those ideas during his work on this album.

It’s not all about the music, though. ‘Flow On’ has Cold 187 and K.MG rapping alternate lines, each adopting and improvising a new kind of half-sung flow to insinuate their lyrics into the slow soul groove. It’s dextrous and innovative, and clearly paves the way for later master stylists such as Snoop. ‘Another Execution”s saga of disrespect in a cinema queue leading to gun violence is richly detailed and incisively observed – and, set to the daringly slow beat (the Lyn Collins sample checks in at around 73 beats per minute, with the average hip hop head-nodder being at least 92bpm at that point), the carefully sluggish intonation required to rap over it adds a hefty dose of menace to a song where the subject matter hardly lacked in that quality to start with.

Best of all is ‘Freedom of Speech’, which again features three verses from 187 on his own, and uses half of the First Amendment to the US Constitution as its hook. The song begins as nothing more sophisticated than a defence of a rapper’s right to swear on records, but soon adds a level of nuance and poetry rarely seen when hip-hop has tried to discuss these issues:

"I get wild every rhyme I release

Whether I talk about violence or talk about peace

‘Cos violence is somethin’ that happens in society

When people are livin’ low and don’t know where they can go

But peace – I think we all want peace

But it’s too much to face, and it’s too far to reach

Whether I say my rhymes fast, slow, sloppy or neat

See, I wish when I’m doin’ it, to have freedom of speech"

It’s by no means a record that can be recommended to all listeners, and there have to be significant caveats placed around parts of its lyrical content, even as other parts show a group clearly aiming far higher than many. But for anyone with even a passing interest in gangsta rap, anyone keen to understand the development of this most divisive and problematic of sub-genres, and anyone who just wants to hear a hip hop record made with as much apparent care and attention as tended to get bestowed upon a big-budget rock album, Livin’ Like Hustlers remains essential listening.