Research for this piece – a few clicks – tells me this is "generally regarded as Gabriel’s finest record”. I had no idea. My impression was that it sold well on the back of the hits ‘Games Without Frontiers’ and ‘Biko’, but that its chilly jaggedness was too much for the consensus and that it was only fully appreciated by freaks like us. I’d assumed So was his best-loved album, because by then Hollywood were using his material in movies and the dreadful, plodding ‘Sledgehammer’ had that ubiquitous, admittedly pioneering, video. Over the course of the 80s Gabriel got very successful and revered and politically correct, and lost what made him unique. He got so big and benign and respected that he couldn’t risk confessing any more, wouldn’t document the pirouettes of his hungry psyche.

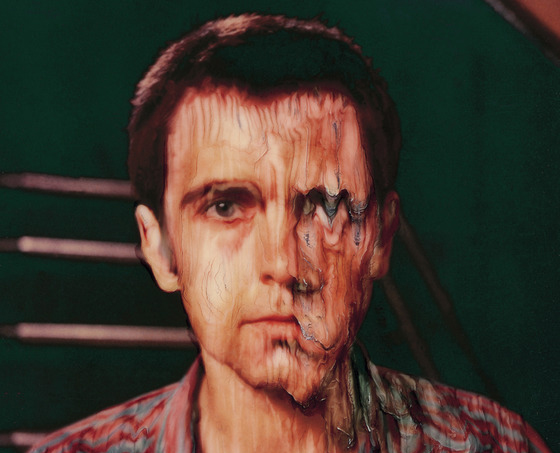

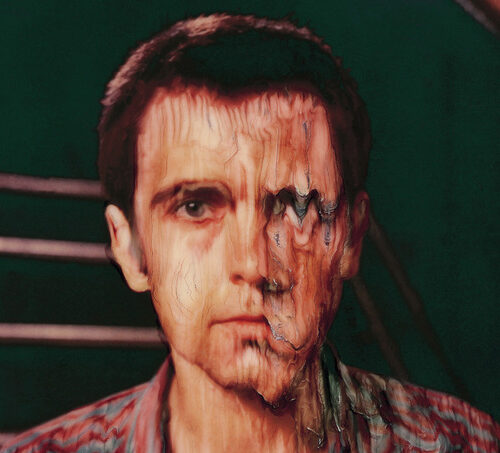

What made him unique is all over 1980’s Peter Gabriel 3 to the point of making it sticky, clammy. The third successive solo album to be called, officially, Peter Gabriel, it attracted the nickname Melt, because of its Hipgnosis sleeve. It’s some crazy shit.

Arty prog-pop. Funk in negative. Depressed, romantic, twitchy, paranoid. You look in its eyes and you fear for its safety, and maybe your own. Here be monsters, in icy, literate, tales of stalkers, assassins, persecuted immigrants, ordinary people who fear they’ll do some damage one fine day, outsiders all. It reveals fresh treasures and kinks even 40 years on. At this time, remember, Gabriel was still trying to lay the ghost of Genesis. He was more identified with the band’s earlier, baroque work than he was with his own. He was the man who’d pondered, “A flower??” in the 26-minute ‘Supper’s Ready’ while wearing a fox head and a red ballgown. He’d punned and fretted his way through four sides of The Lamb Lies Down On Broadway. He was theatre rock. But then he’d killed Ziggy. The first two solo albums – despite moments like “Solsbury Hill” and “Modern Love” – had begun to define him in a separate space, but not yet clarified what was going on in that space. Besides, far from feuding and falling out with the remaining members of Genesis, he was on good terms with them. Phil Collins appears on drums here, as he does on so many exquisite albums of the era, putting down markers despite the world of music journalism’s lazy, petty, perpetual loathing of him.

PG3 is where Gabriel ascends, where he hits the perfect point on the curve between artistic ambition and accessibility, between dark and light, between floridness and reticence. Songs, themes, sonics and presence come together to create a cohesive yet many-limbed piece which pitches up somewhere between Lodger and Scary Monsters. Challenged by the NME at the time about Bowie comparisons, he replied defensively, “I get the feeling he’s more calculating. There’s not too much coincidence emanating. With me there is still quite a large functioning of randomness, accident and mistakes.” Going on to praise Bowie’s willingness to keep moving, he added, “You must let go of what you’ve got, cause if you try and clutch on to something which you think is yours, it withers and dies.” It would be facile to pin this album as an anti-Genesis statement though: much of it is every bit as self-important. It’s just leaner, sharper, quicker to make its points. It’s speed (with all the nervous glances over the shoulder), not dope, not comfortable or relaxing.

While this will not turn into a detailed discussion of drum sounds, it has to be mentioned that the outstanding, ominous opener ‘Intruder’ is where the “gated drums” technique which so dominated and ultimately defiled the subsequent decade was invented.

Gabriel and (the then very fashionable) co-producer Steve Lillywhite banned cymbals, asked Collins and Jerry Marotta to adopt a less-is-more approach, and found the results to be sinister, dramatic and arresting. (Freeing up the higher frequencies thus allowed room for exploration that few artists had realised was possible. They used the spaces for creaks, screeches, whistles, sirens and found sounds that are just as important to the record’s feel as the conventional keyboards, guitars, etc. This subsequently became common practice for a while, then it wasn’t, and now – in a period where music has a chronic lack of drama – it would be good if it was again.)

‘Intruder’ is an extraordinary piece of creepy-sexy art-rock. The protagonist is an up-to-no-good stalker, breaking and entering, part-Hitchcock, part-care-in-the-community. The detail of this sad-scary character’s lusts and motivations is intense.

“I’m certain you know I am there… I like the touch and the smell of all the pretty dresses you wear.”

To ensure that this weirdo cannot be confused with the avuncular do-gooder we now perceive Peter Gabriel as, "Intruder come and go and leave his mark.” Ugh. A bold, unsettling, sleazy and poetic gambit. Menace. No glib catharsis.

‘No Self-Control’ – a single, bizarrely – is a confessional of a man teetering on the verge of a nervous collapse. “I don’t know

how to stop… I’m so nervous in the night… there are always hidden silences.” It’s a compelling construct of synths and riffs, of hooks and descent, echoes and loops, beautifully structured and subtly aggressive. After the brief instrumental respite ‘Start’, in rages ‘I Don’t Remember’, another examination of mental frailty. “I’m all mixed up, I got nothing to say…” Perhaps more conventionally rock-pop, it’s yet riddled with quirks and counterpoints. Gabriel’s scorched, frayed voice(s), as throughout, are raw yet tender, deft yet decisive. Our next misfit is the would-be hit man of ‘Family Snapshot’, a Lee Harvey Oswald manqué who plans to assassinate a celebrity (a president?) because it’ll make him famous, amid the "camera crews” and “peak-time viewing”. As social documentary/ satire it seems old-hat now, but this was 40 years ago, two decades before Big Brother. Like most of the album, it goes for big statements with delicious knack for understatement.

‘And Through The Wire’ is relatively straight-ahead rock, but after the repeated teaser of “I want you”, that’s one doozey of a chorus, and he sings the title line like he’s gargling emeralds. You’ll know ‘Games Without Frontiers’ (with a barely audible Kate Bush on backing vocals). As an anti-war lyric it’s facile; as a pop song it’s a peach. ‘Not One Of Us’ is a prescient piss-take of the NIMBY anti-immigration lobby. “A foreign body… and a foreign mind… never welcome in the land of the blind.” Then comes the track which grabs you last but, after many listens, grabs you hardest. ‘Lead A Normal Life’ is barely there, a whisper, a rivulet. It can be interpreted as an asylum inmate’s murmurings as he glimpses the trees. It haunts, in your peripheral vision.

You keep returning to it, like a flicker of a memory, willing it to catch flame. Grand finale ‘Biko’ signals where Gabriel was next to travel, becoming pop music’s patron saint of all things worthy and earnest.

That said, his story of the murder of the apartheid activist, even with its big singalong coda, is lyrically extremely restrained and pointed, eschewing see-how-clever-I-am imagery: “The man is dead, the man is dead”. And again, one must recall that the first people to champion good causes should not be blamed for those who later jump the bandwagon to further their own careers. This is not Geri Halliwell posing with Nelson Mandela. This is a guy singing about something few people in the Western world had then heard of.

Musically alive and daring (we haven’t even mentioned the contributions of Robert Fripp, saxophonist Dick Morissey, John Giblin’s gallumping, gorgeous period bass or, er, Paul Weller’s guitar cameo), lyrically and vocally astute, this is an auteur’s album, with sound and thought and feeling in perfect step. It confirmed him as not just “the ex-Genesis frontman”. It ensured he wasn’t swept away by punk’s blinkered absolutism. It should have been the beginning of even better things, but wasn’t quite.

In 1980, for one album only – a murky, mirror-gazing masterpiece – Peter Gabriel was the finest exponent of art-rock in the world. Savour it, with the seductive, sentient shudder it prompts.