The Smiths’ split in summer 1987 couldn’t have come at a much better time for The Wedding Present. Over four years, the Mancunians had assembled a strange and broad coalition of fans, one large enough to make a genuinely odd group staples of Top Of The Pops and regulars in the charts. They appealed to indie hardliners, to sensitive kids of both sexes who wanted their own insecurities sung back to them, and to the kind of lads who didn’t like hard rock but wanted something boisterous and muscular to throw themselves around to. (This last group tends to get written out of Smiths history, but it was a large and vital part of their constituency. Smiths gigs were not for the faint-hearted.)

Once Morrissey and Marr parted ways, The Wedding Present seemed like the natural destination for large numbers of those fans. They weren’t just indie, they’d set up their own Reception label on which to be indie; they had the Northern kitchen-sink romantic singer/lyricist in David Gedge (albeit one whose lyrics didn’t trade in ambiguity in the way Morrissey did); they had melodies indelible enough that the real charts became a possibility for them; and they had muscle, too: The Wedding Present had far more in common with Hüsker Dü than with, say, the version of Primal Scream alongside whom they appeared on the NME’s C86 cassette.

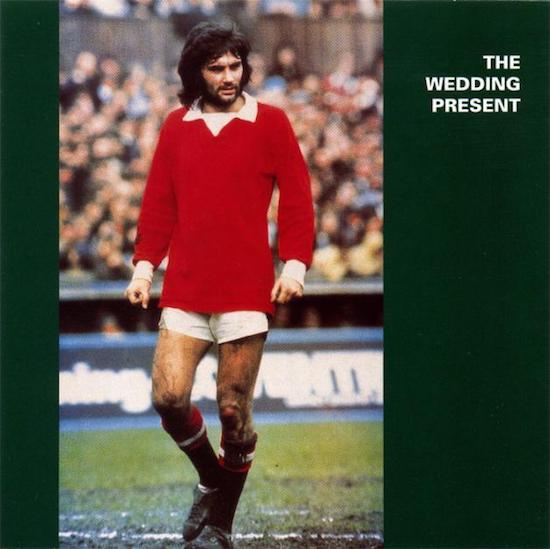

When George Best was released on October 12, 1987, it was an event, in indie terms. It was the big display item in independent record shops; the early copies came a George Best carrier bag and a white vinyl 7" of ‘My Favourite Dress’. The Wedding Present were rewarded with a No 47 placing in the album chart, the real chart. That doesn’t sound like much now but for an indie group in 1987 it wasn’t far short of the achievements of Alexander The Great. (For context, look at their fellow C86 frontrunners: Primal Scream’s first album – with major label backing, reached No 62 a week before; Shop Assistants’ debut scraped to No 100 late in 1986, also with major backing; The Mighty Lemon Drops, once again on a major, reached No 58 with their first album; in 1988, the Soup Dragons’ debut would peak at No 60.)

The Wedding Present had been building up to George Best for a little under three years, building up to it with a series of singles, each a little better than the one that came before: ‘Go Out And Get ‘Em Boy’; ‘Once More’; ‘This Boy Can Wait’/’You Should Always Keep In Touch With Your Friends’; ‘My Favourite Dress’. John Peel supported them, and Strange Fruit released a Peel Sessions EP in 1986, that was perhaps even better than the singles they were recording themselves on threadbare budgets. They were lumped into C86 – a far more varied bag than the popular conception of it as a compilation of the fey and the milquetoast – because their music seemed to draw on some of the same sources (Orange Juice, Buzzcocks) as the other bands, even if it came out sounding rather different.

George Best was an important record in British indie music, albeit not necessarily for the intended reasons. Although it was greeted with overwhelmingly adoring reviews, there were occasional naysayers. Among them was one early supporters, Chris Roberts of Melody Maker who noted that while the group sounded breathlessly exciting in four-minute doses, that excitement rather dissipated over 40 minutes. In an interview early in 1988, a clearly irritated Gedge took Roberts to task: "It was the worst review we’ve ever had. We were really disappointed, cos it was the first one out and we thought, ‘Oh shit, this is from someone who likes us.’" Roberts didn’t apologise. Instead he asked Gedge: "Has no one else ever said your songs all sound the same? Ever?"

Given a glut of the things, it became easy to parody Gedge’s songs. Take some folksy Northern patter for a title – Scraps On Your Chips, Pet? – play the guitar very fast, add a lyric about your girlfriend leaving while you’re out walking the whippet. The Wedding Present made music that was unrelentingly prosaic and parochial. It was, of course, deliberate: it was an inheritor of punk and post punk’s suspicion of fake glamour, and it resonated profoundly with late teens and early twentysomethings for whom glamour was something so remote as to be not worth even aspiring to. The dress code of the fans reflected the dourness of the proposition: DM shoes, jeans, jackets from Oxfam, faded shirts.

You see the heirs of George Best not where Gedge, I suspect, would like to see them, which would be among the doggedly underground bands of the DIY scene. Instead the characteristics of George Best-era Wedding Present cropped up in the bands of the indie landfill – The Pigeon Detectives, The Fratellis, The View, and so on. Bands defined by their regionalism, their commitment to being at one with their audience, and focussed on making every song into a delivery mechanism for a singalongalads chorus. That’s a harsh assessment of The Wedding Present as a whole, because Gedge refused to stand still, and two albums later, with Seamonsters made a record that really does deserve to be talked about as one of the great British guitar albums of its age, a dramatic leap ahead of the competition whose place in history is lost because it came out either two years too early or two years too late, and was submerged beneath the breaking wave of baggy. And so George Best has always remained the landmark album, the one that defines The Wedding Present. It’s the one that gets revisited for whole-album gigs, the one they’ve rerecorded with Steve Albini (those recordings, made a decade ago, are being released this autumn for the 30th anniversary).

Hindsight, of course, is easy. George Best‘s conservatism didn’t seem quite so evident at the time. Perhaps those of us who loved The Wedding Present were aware that they could never equal The Smiths, melodically or lyrically. But they were what we needed at the time, a band who very clearly spoke for the "us" who were morally opposed to music that made its practitioners into superheroes, who were crap with the opposite sex and unsure about what place we were meant to carve in the world. The musical certainty of George Best gave us what we craved, and the excitement of rushing guitars into the bargain.

The thing we should have noticed, really, was how male it all was (Roberts did notice, and put it to Gedge, who maintained The Wedding Present were "asexual … Aimed at everybody"). This is not to traduce Gedge, whose actions have always been impeccable: The Wedding Present often had support bands featuring women, among them Talulah Gosh, whose Amelia Fletcher appeared on George Best; later iterations of The Wedding Present and Gedge’s other group Cinerama included women.

On the one hand, the maleness is unavoidable. Gedge, a limited singer, could never sound like anything other than what he was: a bloke from the north. And the music – forthright, loud and sometimes clunky – was what brought in the geezers (and come they did; I recall one show in Leeds, a benefit for Nicaragua, that descended into a face-off between the university rugby league team and a busload of Manchester United fans who’d come over the Pennines looking for a scrap). But it was not wholly unavoidable: the lyrics to George Best deserve some attention.

It’s clear that Gedge is sometimes writing in character, and that the character isn’t always meant to be sympathetic. But no matter who the protagonist is in any song on George Best, he is always disappointed by women, and women exist in these songs only in terms of their effect on the mental wellbeing of men. It’s an almost Saudi view of things. There are two kinds of women in the songs of George Best: the ones who betray, and the ones who are so without agency that they stick with terrible boyfriends, even though David’s here and he’s so much nicer. ("And when they’re out with all his friends he just forgets that she’s even there," he complains on ‘Don’t Be So Hard’; "These days you look so pale and thin / Wave down a bus and let’s be rid of him," he suggests to the woman who’s being abused on ‘Shatner’.)

It’s a perfectly reasonable position to argue that when one is writing songs about heartbreak, then it’s natural that the focus of the songs will be the feelings of the heartbroken person. But, as Roberts noticed with regards to the music, the sameyness becomes the issue. In real life, when one meets a man who seems perpetually to be complaining about their mistreatment by women, one starts noting that the common factor in all these break-ups is them, and begins to wonder quite what he does that makes women leave with such frequency. Likewise, listening to ‘My Favourite Dress’ now, I don’t feel the sympathy I did when I was 18. I wonder what the narrator was doing to cause the woman to want to sleep with someone else; I raise an eyebrow at the Tony Parsonsesque quasi-masculinity of "the tender caresses that bring out the man", as if "the man" is some higher condition that any woman is duty bound to help her partner achieve; I wish I could ask the narrator why he views the relationship in terms of possession – "A stranger’s hand on my favourite dress".

Gedge was a young man when he wrote those lyrics. I suspect he would not write them now. And this is with the benefit of a) hindsight b) the perspective of having known a great many more women (and had more relationships) than I did when I was 18, obsessing over George Best and c) the significantly greater awareness of male privilege that I now have. Nevertheless, lyrics that seemed to me at the time to be an admirably moralistic view of human relationships now seem angry and judgmental; the line in ‘My Favourite Dress’ that "jealousy is an essential part of love" is the one that sums up the worldview of these songs. It’s worth remembering, though, that these are songs of youth: my perception of them has changed as I have got older. I fully empathised with that view of jealousy and love when I was 18, but now I have been married for 20 years. I would not be in the least surprised if Gedge looked at some of those lyrics and wondered what on earth he’d been thinking.

It’s no surprise, I think, that ‘A Million Miles’ became a fan favourite (No 8 in Peel’s 1987 Festive 50, with ‘Everyone Thinks He Looks Daft’ at No 3, ‘My Favourite Dress’ at No 6 and ‘Anyone Can Make A Mistake’ at No 10. Different times, folks). ‘A Million Miles’ is the most tender, least judgmental song on the record, a song about falling in love, before the romanticism has been bruised: "I kept bursting out with laughter all the way home / I had to tell somebody, and you just happened to phone / I can’t think of anything else, no matter how I try / But, you know, I can’t even remember the colour of her eyes." I’m not sure whether the song is strengthened when the final refrain of "You’re not like anyone I’ve ever met" is suffixed with "at least not yet". On the one hand, it’s a note of tartness in a song that’s otherwise all sweetness; on the other, there’s so much tartness elsewhere on the album that it’s not necessary here.

If the late mid-to-late 80s was when indie became codified as, fundamentally, "music played on guitars by young white men" – we can quibble around the edges, but that’s the long and the short of it – then The Wedding Present became, for better or worse, its standard bearers. The sweep of a long and interesting career – experiments with noise, lofi, Ukrainian folk music – is reduced to this: lovelorn blokes playing loud. I wish that weren’t the case, for The Wedding Present were for a long time my favourite band, but that’s the truth. By making something that had the laudable aim of being non-elitist, The Wedding Present helped dig the hole that became the indie landfill.