Last Thursday evening marked the climax of one of the strangest periods in my recent life. It kicked off when I attended the funeral of an old colleague, at which I interacted for the first time in 18 years with people I had worked with in stressful situations on a regular basis back in the old psychiatric hospital system. Together we lamented the death of a man in his early forties, who had essentially drank himself to death. The following morning I attended a high pressure interview for a senior operational management post in a prison, and from there I went to a wedding to witness an old friend from way back experiencing, in his own words, the best day of his life. In that day and a half I experienced a curious lack of emotional response to the stress and situations, and despite my best efforts to have fun my mood was largely flat throughout.

This morning, however, I heard on the radio while driving the news that Tony Scott, at the age of 68, has died after throwing himself from a bridge in Los Angeles. Letting out a strangled yelp I choked back an involuntary cry of dismay. It wasn’t because Tony Scott, director of Days Of Thunder, is dead; rather it was the manner of his death that forced me to cry out in shock.

Why did this event trigger a seismic release of emotions? I never knew him and, with the exception of the greatest film of the 1990s True Romance, I’m not a particular fan of his oeuvre.

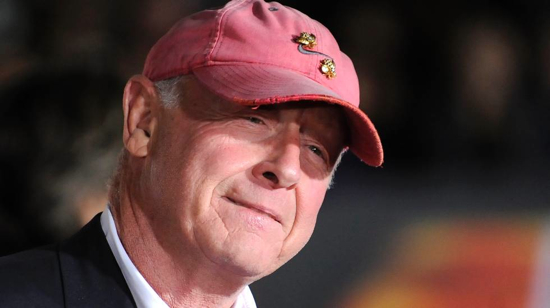

Although his directing career started with the artful and erotic vampire thriller The Hunger, Tony Scott was best known for redefining the standard for ultra-commercial action movies in the ’80s. That decade saw his best known and loved movie Top Gun, the original sweaty bromance that launched the career of Tom Cruise into the stratosphere. An overnight success, Scott helmed numerous other blockbusters including The Last Boy Scout, Crimson Tide and Enemy Of The State, plus a whole host of Denzel Washington vehicles that made lorry loads of money at the worldwide box office. He was well-loved by his colleagues, seldom seen without his trademark baseball cap and cigar, and warmly self-deprecating in interviews.

After recently passing on making the next Wolverine film, Scott was nevertheless a busy man, lending his considerable experience to the TV adaptation of Kate Mosse’s phenomenally successful novel Labyrinth. He was also reportedly busy in pre-production on a sequel to Top Gun. In short he was a phenomenally successful, A-list Hollywood movie director, just like his older brother Ridley. But, like Gary Speed last year, Tony Scott’s case demonstrates that depression does not recognise or respect status, wealth or the perception that many of us have regarding the importance of those two factors in happiness and longevity. When I heard the news that this high profile, successful British talent had succumbed to the worst that depression has to offer, it hit me in the head like a trepanning drill and the pent-up emotions of previous days flooded out.

In mental health circles depression is generally described as a ‘mild to moderate’ mental health condition, whereas the more terrifying and unfathomable spectre of psychosis is generally classified as severe. This despite the fact that in some cases depression leads to the ultimate form of negative thinking, that death would be preferable to keeping on living, and despite the fact that one may suffer a psychotic illness for a period of weeks, but recover and never suffer it again.

Depression is a powerful illness. It can be difficult to detect and it is convenient for us to dismiss, but it is serious, common and can all too easily become a killer.

Tony Scott leaves behind an impressive portfolio of slick adventure films as a legacy, but he also leaves behind a wife and two sons who will now struggle to quantify his actions and square them with their own perceptions of him as a man, as a husband and as a father in his last few months of life, and that is a tragedy.