As far as combinations go, one of music’s most photogenic groups plus one of rock’s most revered photographers is as good as it gets.

After acclaimed books of his work with The Cure and Paul Weller, the revered Tom Sheehan’s new book You Love Us, a deluxe hardback release compiling both famous and unreleased shots of The Manic Street Preachers from 1991-2001.

Spanning the band’s early years before the release of their debut album Generation Terrorists (for which he also took the now-famous album cover) to the band’s performance in Cuba and post-gig meeting with Fidel Castro, the book covers the entirety of the Richey years as well as the band’s rise to megastardom after his disappearance.

We’ve got a deluxe edition of the book worth £70 to give away, as well as an interview with the venerable Mr Sheehan about his relationship with the Manics below.

To win, send your answer to the question below to comps@thequietus.com before midday next Friday (September 8).

Which of these tracks did not appear on The Manic Street Preachers’ Generation Terrorists?

A: Roses In The Hospital

B: Stay Beautiful

C: Slash ‘N’ Burn

Tell us more about your first encounters with The Manics

I didn’t know fuck all about them when we first met, I was the chief photographer at Melody Maker, and for some reason I’d booked a studio, I was in the habit of just getting some beer in, having a few drinks, not in a crazy kind of way, the juice just helped to oil the parts.

While I was talking I just got their shirts and put them on a coathanger and just photographed each one of them. As it’s the representative of them as a band, knowing that their endeavour was sloganeering. It was a shorthand version of getting their message across. A lot of the time with journalists and photographers they inflict themselves on the band, I don’t think I do that. I’m there to help, what’s the point in a hatchet job. I thought I identified where they were coming from, they were more than willing to take the images to another place.

Is this before they really built up the notorious reputation of their early days?

I think at that point they were still knitting the jumper if you will, this was before the first album. If you are from the environment that they come from, if you’re striving and starving to get up and say something, it isn’t enough to just have a few slogans on your shirt. They had to make these statements like ‘This is the only album we’ll ever do, a double album that will sell sixteen million copies then after that we’re gone’. It was fantastic, everybody was going to pay attention.

What were your first impressions of them in person?

I think overall the impression was that there were these turks from out of town, and they were absolutely charming in their endeavour. It’s hard for young musicians to nurture themselves, and with their bluff and bravado I just thought it was fantastic. As with all bands, they were flying the flag and what it said on the flag was what they believed in, but when you break it down to the components of the individual musicians, they’re all different people. They’d got themselves out of Blackwood and formed a band, that was a statement in itself.

Did you form a close bond with the band?

We never formed a close bond, the thing is that when you’re working with groups you only want to work with them when you’ve got something to do. I love the fact that when you meet a band you get on and you create something and it’s run that week, then you meet again. Everyone has their own way of working, but I love the way that say with those chaps you’d be put in a situation where the environments are different. I’m an old geezer, what I’ve learnt is down the line is miles in the past, but they were learning on a daily basis, to deal with life, the industry, their own creativity, everything. Whenever I see that I think ‘I wish I could’ve been like that when I was 20’.

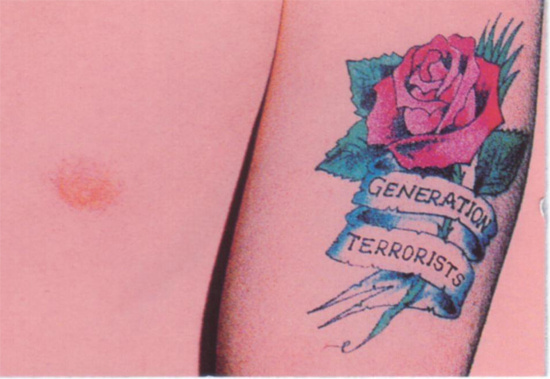

You’re also the man behind the Generation Terrorists album cover…

The only time I worked for them was the first record sleeve. We did it in a garage, it was raining outside, Richey had the flu, he was there with his shirt off, but at the end of the day came the picture that we had. After doing that there was an idea of talking about doing stuff with the EU flag, so we photographed that and set light to it and took pictures over in a studio in Clerkenwell. We just photographed the flag burning as a print, the fumes gave me a tremendous headache…

It came about through them, Philip and the label. There were a lot of non-believers at the time, a lot of people went in for that endeavour, but others just dismissed them out of turn, unfairly. Would you have known they’d been carrying on 25 years down the line? All you’re dealing with is what’s in front of you at the time.

Which is your favourite of the shots in the book?

I hate talking about my own shit, and that’s why a lot of the stuff that’s in there hasn’t really been seen, because I never really syndicated. There’s a picture taken by the Karl Marx statue in Highgate Cemetery which is brilliant. I had this new lense, a small depth field, which means you can focus on one person and leave the rest blurred. There’s one of Rich with him in focus, and I never wanted to do the ‘Saint Richey’ thing, but it really worked, I just love it. I didn’t want it to be Richey in the catacombs or with a load of skulls, that’s rubbish!

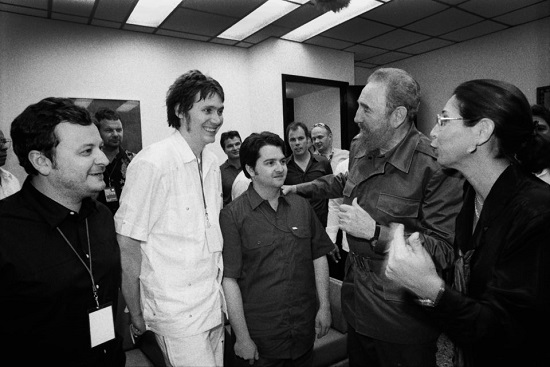

You also went with the band on their infamous trip to play in front of Fidel Castro in Cuba, what was that like?

The Melody Maker had closed and they took me on at the NME, like care in the community. Unbeknownst to me the cover shoot was already done once we’d set foot on the plane! It was extraordinary, I’m not really one for glamorising poverty. I was born pretty poor and I’ll die pretty poor, it’s not glamorous to look at shitty towns, but fuck me Cuba is brilliant. It’s very strange, each of the documents that you had to procure, your visa, accreditation, costing 99 dollars a shot. They played a great show, then afterwards there was talk of meeting Castro. Me and Ted Kessler, the NME journalist thought we’d missed it but we were taken through another door, we’d snuck in! It was kind of inappropriate, this world renowned guy talking to these chaps who were excited to meet him, and intimidated I assume. He had an interpreter, I think that was a foil to not get too close. It went on for 10 minutes or more, they got up, shook on, and I shot myself in there and rattled some frames off! James goes ‘Fucking hell Tom!’ and I said ‘I can’t miss this!’. It’s unlike me to foist myself, and the pictures are shit, but documentary wise it’s great!

Was there any backlash from Castro and his people?

I wasn’t told not to take a picture! I just did it. I took the film out and put it in my pocket and then an empty film in the camera, just in case anyone wanted to take it. Ah, the pre-digital years!

What were the differences photographing the Manics with Richey compared to without him?

None, really. Obviously Richey’s an incredibly good looking chap, and a lovely chap, but when you’re there you’re just there to spend half an hour doing what you’re meant to do. It’s dangerous if you think about anything a band’s done before. You might have history down the road, but you can only deal with what you’re dealing with at the time. When Richey was in the band it had a kind of sparkier, freer mood, he was integral to the band, but what did he actually do on stage? The Manic Street Preachers couldn’t exist without him, yet they did. If you’ve got the talent they’ve got for reaching out to people, and Rich was only a part of their endeavours, there was no reason they should stop.

You’ve had books out of photos of The Cure and The Jam, why were The Manics your next choice?

They’re just one of those people. I’ve always loved their endeavour, what they wanted to do. I could have done Oasis or Blur, who might be higher up the ladder, but I loved what The Manics were going for, from top to bottom. When it was Richey’s birthday I sent him a Neil Young record, I thought he might enjoy it, then next time we met Rich was playing Gram Parsons, while Nicky’s furious with me for getting him into it – “This is all your fucking fault Sheehan!”