"We’re all gonna die!" rings Sufjan Stevens’ voice around the Royal Festival Hall at the close of ‘Fourth Of July’. The singer-songwriter has ramped up the synths that waver in the background of the recorded version so that rather than a spectral gauze, they now spill over and burble at the end of each verse, eventually building to an all-encompassing crescendo, shot around the hall on the back of spotlights and lifting the reprise into a sort of meditation on death’s inevitability, wrought with a bleak humour that gets a little less so with each declaration.

Death figures large in Stevens’ current live show. Two nights ago in Manchester, after he and his band had finished performing songs from Carrie & Lowell, the collection of songs written in the wake of his mother dying in 2012, he told some anecdotes about his family’s close relationship with death. As a child his parents would give him birthday cakes iced with a question mark and the message, "You never know when you’re gonna go", and bedtime readings from his mother would come from the Tibetan Book Of The Dead, he recalled in a loving and very funny, dry tone. At around the same point tonight, he says: "We have passed through the vortex, and survived." The sentiment is one that’s tangibly shared by the audience, who laugh appreciatively, with a touch of relief. The statement also maybe acts as a signpost for where Stevens has arrived on his journey: death doesn’t feel like an oppressive, sepulchral blanket here; it’s more that we’re at the stage subsequent to a sadness deeply felt, now accepted and lived out through these beautiful songs.

That’s not to say that the rending intensity of the album is in any way diminished. His mother Carrie had been, by and large, an absent figure in Stevens’ life, leaving when he was one and, after three summers they spent together in his childhood with his stepfather, Lowell, only a sporadic presence until her death. As such, she became a partially-imagined figure, an almost complete absence that the album addresses; "Her death was so devastating to me because of the vacancy within me," he’s said. Out of the vacancy comes a bracing encounter with what he can remember of his mother. "Again I’ve lost my strength completely, oh be near me/ Tired old mare with the wind in your hair," sings Stevens on ‘Death With Dignity’, the first song from the album, and the second tonight, after the choral opening of ‘Redford’. Just as on the record, there’s no comfort to be found in a sympathetic string swell, nor is directness dispersed through a complex arrangement for massed musicians: Stevens simply sings his observations, concrete and metaphoric, ending on, "Five red hens – you’ll never see us again/ You’ll never see us again", over the cascading finger-picking of three guitars. Elsewhere the songs get taken down a different path, ‘Should Have Known Better’ ending with a strobing, escalating keyboard solo over the drum machine-powered coda, while the plaintive guitar slashes of ‘Drawn To The Blood’ reach for a gnarled, electrics-lined end.

The heart of the songs, though, remains bare and determinedly purposeful. "It’s something that was necessary for me to do in the wake of my mother’s death," Stevens said of the album, and this sense of Carrie & Lowell being a means of working through his response to death remains: the images of suicide in ‘The Only Thing’ and the lines, "There’s blood on that blade/ Fuck me, I’m falling apart", remain bluntly, viscerally painful, especially when rendered in the here and now, Stevens’ voice even more singular, vaulting and almost preternaturally close-feeling than it is on record.

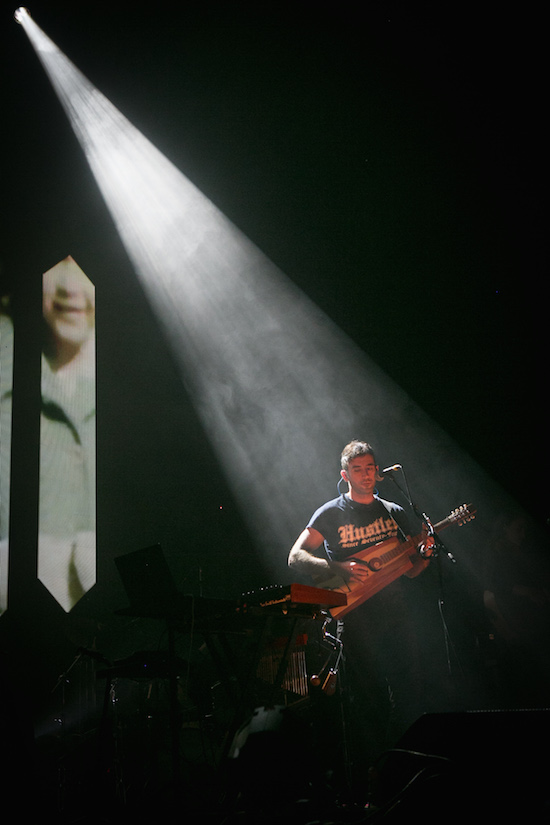

Two older songs, ‘The Owl And The Tanager’ and ‘Vesuvius’, get folded into the Carrie & Lowell cycle, the dance moves he accompanies the latter with a vestige of the last time he played the Southbank, for the fluorescent, confetti-covered The Age Of Adz tour, before he ends it with ‘Blue Bucket Of Gold’. The song’s ending builds into a ten-minute-plus crescendo, with the sacred overtones that resonate with most of Stevens’ music teased out when revolving mirrorballs reveal Nico Muhly, special guest accompaniment tonight, playing the towering organ at the back of the hall. Vast and overwhelming, the wave of sound feels like a fitting monolith to the heft of the record’s subject matter.

After a standing ovation, Stevens returns for an encore that’s one extended joyous treat, a bit lighter in tone but still fitting with what’s just gone down. The leaping piano of ‘Concerning The UFO Sighting Near Highland, Illinois’ is followed by the banjo-led ‘In The Devil’s Territory’ and a gossamer rendering of ‘Futile Devices’, finished by a bafflingly brilliant Casio SK-1 solo by the powerfully hirsute Steve Moore ("who also goes by the name Zardok"). Way out of the vortex now, Stevens dedicates ‘The Dress Looks Nice On You’ to singer-songwriter Dawn Landes, a member of the band for this tour, in the process explaining how the song’s about common courtesy, something the English are fond of, as our warning not to "dazzle" other drivers shows: "in America, ‘dazzle”s like razzle dazzle, like a gay parade; here, it’s just lights… management").

There’s a final trio of ‘John Wayne Gacy, Jr.’, ‘To Be Alone With You’ and ‘Chicago’, a bow, and done. At Manchester, Stevens had delivered a prayer for the night, one which reflected how his experiences of death had come to make him view it as a constant companion, one which should prompt us to "live with every breath", and tonight, in the same spirit, he says: "It’s been a long and horrible journey – your whole life leads to right now, and I wouldn’t want to be anywhere else." That final sentiment, you suspect, is something shared by everyone in the room, and it’s hard to feel anything but gratitude for being party to the last two hours. Not just because it was, for this writer, one of the best shows of the year, but because it was the end result of that vacancy being transcended, the loss of death transformed into something brimming with life.