What’s that you say? Science and extreme music? Powerful sonic waves in a machine used to work out if aeroplanes would stay up-diddly-up-up and not come crashing down-diddly-down-down? A licensed bar? Why, this sounds like our ideal Sunday afternoon. Speed Of Sound is a one-off experiment and sound installation taking place at the Grade I listed Farnborough Wind Tunnels featuring work by Dalhous, Cindytalk, Teleplasmiste and a talk called ‘Sound As Terror’, a presentation of sonic research into the use of drones in contemporary conflict. We are told that: "The programme is particularly interested in the shape, form and function of airflows, waveforms; sound and sonic instruments. Speed Of Sound will creatively extrapolate the history of the space and its uses, whilst immersing the visitor in the special dynamics of the site. In the case of the wind tunnels, air moved through architecture designed to manipulate its flow. The shape and form of its journey then registered mathematically and used. The wind tunnels lay silent, a monument to changes in aerodynamics and aviation, but the ominous rumble of militaristic advancement still remains on the edge of hearing." You can find the Facebook page of the event (with details of a cheap coach to take you to and from the sonic basting) here. We spoke to organisers Susanna Davies-Crook and Alastair Frazer to find out more.

How on earth did this marvellous project come into being?

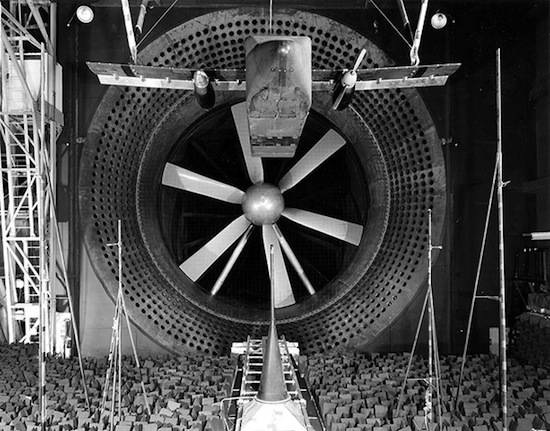

Susanna Davies-Crook: I saw an e-mail in my Royal College of Art inbox marked "Farnborough Wind Tunnels" and thought it could be cool. Interested parties went on a field trip to the tunnels in a vintage double decker bus driven by Joe Kerr and when we arrived it was breathtaking. Not just the architecture and the massive (24ft) mahogany hand-crafted fan, but the way the engineers who had formerly worked there spoke about the place. Their attachment to the building and the research that it hosted between the time of its opening in 1935 to when it officially closed in the 90s made the site feel like it was holding all of this history. Although it’s now decommissioned, it’s still the same as when it closed. All of the rooms and the instruments remain untouched and intact.

On the visit we were shown around by the Artliner organisers and they explained about the public programme, but every now and again one of the engineers or physicists who used to work on the tunnels (and now manage and archive the history of the wind tunnels in the FAST museum) would divert someone off and in one case it was me. I climbed the steps to the smaller Transonic wind tunnel and there was a scale model that had been used for testing still laying there with wires protruding from it. I asked my guide about the wires, and he replied that they were how they measured the air resistance. The device was essentially a transducer. As I asked more and more I discovered links between acoustics – the kind I am interested in with regards to music and experimental sound – and aerodynamics. He explained that they test helicopters by placing them exactly in a ring of microphones and then taking readings that help them determine the efficiency of the blades. The whole of Q121 was at one point covered in anechoic foam. I just wanted to know more really, about the history and technologies, and about how the space had sounded and would sound in different circumstances.

Can you tell us about the Farnborough Wind Tunnels?

SDC: I can’t explain as well as Graham Rood or the people that work at the FAST museum can – they will all be there on Sunday – but basically Farnborough it is where the majority of British aviation (largely military) advances were born, from the Cody Flyer which is reconstructed in the FAST museum (in 1908 [Samuel Franklin] Cody made the first powered, controlled flight in the UK of a heavier-than-air machine) to the development of Concorde (which Graham explained was perfected by one of the engineers simply climbing a ladder and poking the model suspended in the tunnels). Aside from all the history – they are just extraordinary spaces to be in. The 40ft-high return air duct is architecture designed exclusively for air flow. It is built to house and funnel wind for testing – anything else that is in there is an addition; including us.

How did you select the artists you wanted to get involved?

SDC: We wanted to test the site and frame the correlation between sound and aeroacoustics, but we also wanted to make waves and amazing sounds in the space and see what happened. It’s completely experimental and we’re not sure what it will even sound like – the Q121 space is enormous and all hard surfaces. So in selecting people we invited Mark Pilkington because of his interest in military spaces and UFOs and then discussed how best his introduction to the space would work with the programme and decided that him and Michael J York (as Teleplasmiste) should test it with his twin synths. It will give the impression of a lab experiment as him and Michael York use dry ice and the synth set-up to sweep for standing waves and pump sine waves through the MAAST system. I was recommended Boo and Sami (Sound As Terror) by Jon Wozencroft at the RCA, and thought they would give a good insight into contemporary considerations of aeroacoustic engineering – namely drones. We really wanted to round off the evening by inviting artists to use the space and have music performances that play to the space and directly respond. We’re really lucky that Cindytalk and Dalhous were interested.

AF: There is a lot of dynamic crossover in understanding noise in music and turbulence in aerodynamics, so it felt right to relate this to particular artists experimenting with these ideas within sound practices. Getting noise back energising those spaces feels like a necessary contribution to their reopening, as they were of course hugely loud in their operation.

In the programming, a turning point was forging a collaboration with the MAAST department at Kent University, who are installing their remarkable panoramic diffusion Genelec system for the event. Although we were keen to work with musicians experimenting with acoustic and wind instruments, having gained the extra potential with the MAAST system, it felt right to work with artists we are interested in such as Dalhous and Cindytalk in particular, whose work both related to the ideas behind the project but is also able to test the potential of the sound set-up and the acoustics throughout the spaces.

What have been the biggest technical challenges?

AF: Unexpected difficulties included recent Tory government immigration legislation which is making it increasingly difficult for some international artists to travel as before, so one of the artists we really wanted to invite was not able to make it over. Some of the biggest are certainly still yet to come in managing the sound system and its response to the space, which is an unknown.

SDC: We’ll find out on Sunday!