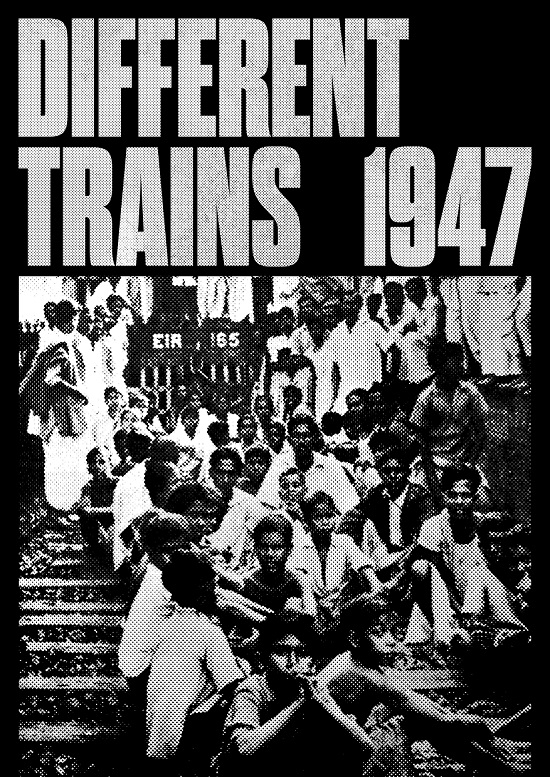

This week, The Barbican Centre in London and Edge Hill railway station in Liverpool will host performances of ‘Different Trains 1947’, a specially commissioned audiovisual performance marking 70 years since The Partition of India, and the creation of Pakistan.

The event saw the largest mass migration in human history, with between 10 and 12 million people displaced as Hindus moved to India and Muslims to Pakistan, and a resulting refugee crisis in cities across the region, as well as constant outbreaks of riots and violence.

The anniversary will be marked with a three-movement re-contextualisation of Steve Reich’s 1988 piece ‘Different Trains’, where the American-based Jewish composer recalled train journeys across the United States during the Second World War, and realised that had he been in Europe he may well have been travelling on a train to a Nazi concentration camp during the Holocaust.

For the new edition, Actress, Jack Barnett of These New Puritans and the Mumbai-based producer Sanaya Ardeshir, in collaboration with percussionist Jivraj Singh and vocalist Priya Purushothaman, will each take on an individual movement, with visual backing from the filmmakers Iain Forsyth and Jane Pollard. Each has taken their own approach, making use of a host of archive recordings and interviews with those who lived through the events.

Ardeshir’s work is the most personal of the three movements, for which she has drawn on her own family history, and her movement will feature the tale of her own grandfather, as told by her grandmother. Below, she speaks to tQ about his story, and her involvement with what is set to be one of the year’s most powerful live events.

What was it about the Different Trains project that stood out so much?

I definitely have moved into a place where concept is playing much more of a predominant role in my approach to writing and composition. It didn’t necessarily use to be the case. Also, Steve Reich’s work was something that was on my radar as something to study and get into. I have a friend who spent many years at a jazz conservatory and he did a module that was derived from Reichian composition, and I remember being fascinated by that idea. I never really had those kinds of opportunities so I started to explore these ideas of rudiments and practise, and slowly it bled out into my practise, into a compositional tool.

And on the other hand I’ve been doing a bit of work recently with a few musicians in Pakistan called the Dosti Music project, a collaborative residency of musicians from India and Pakistan that took place in the US. It was something that was impactful for me because it was just a really odd thing for people from my neighbouring country, in similar practises of work that I’m engaged in, not to be able to interact in a space dedicated to our shared art unless it’s in a third country. It turns my brain into a knot. My family and a lot of families have grandparents from Pakistan, that had to move post-partition. It’s in my knowledge and it deserves to be talked about. I think there’s a part of the story that doesn’t always get represented in a neutral way. So all the moving parts were very aligned with where I was personally.

You’ve drawn on your own grandfather’s story in particular, can you tell us more about him?

My grandfather moved to Bombay from Karachi by train in 1945, not 1947. He was working at a company manufacturing steel cupboards. Although he didn’t have to make the journey in 1947 like so many others, where the stories may well have been darker and more difficult to deal with in terms of content, he had three sisters who were still back in Karachi. From 1945-1947 he had a choice, to move back to Karachi because of the upcoming partition or to stay on in Bombay. Because he had work he said it made more sense to stay, but what followed was that he couldn’t go back and visit his family until after he was married. He and my grandmother went back by train not until 1950.

The interview isn’t with him because he’s passed away, but with my grandmother. She says that he was quite regretful, he was very close to his family. It’s the story of a separated family, of not being able to see his sisters or visit his mum. He had to leave that all behind. The repercussions of that time period really affected so many families. I’ve taken that part of his story, moving to Bombay as a young 27 year old and then realising that there’s a new country being formed out of where you used to live, and that your whole life has been turned around.

How much of this story did you already know about, and how much of it was new when your grandmother talked about it?

I was aware of it, but I don’t think I had the cognitive capacity to really engage with the difficulty of it. I knew my great grandfather was from Karachi, and I had friends whose grandparents were from Karachi too, but I’ve never gone back. It was very eye opening, you hear the stories but you don’t always take the time to really assess what that part of history meant for someone with a real first hand engagement with it. It felt like I hadn’t taken the time to think about just how tough that might have been, and how commendable it is to carry on with your life, to leave a world behind.

Were there any other stories you came across while researching the project that struck you?

Yes there was one. This story is one that was told to us when we were sitting on a skype call with a historian focussing on partition; she was telling us her family’s story. Her grandmother took her three daughters on the train across the border and decided it made sense to move from Lahore to Delhi, where she had some family. They had to vacate from Lahore, but once she got to Delhi it was full of refugee camps, without enough space for all these people. She found her extended family but there was not enough room in the house for four new people. She decided it wasn’t feasible, so she went back to Lahore. When she was trying to board the train into Pakistan a Sikh train guard stopped her and he said ‘I beseech you not to take this train with your three daughters. I know for a fact that people on this train are not going to get off in Pakistan, people might be burnt alive and killed.’ She said she needed to take the chance, that she had a home in Lahore. People were getting picked up and thrown out, mystery stabbings from different platforms on the way, total mayhem.

How aware were you of the artists joining you on the project, like Actress and Jack from These New Puritans?

I was well aware of Actress, as a lot of his work would make its way to gigs I was DJing at. I wasn’t as aware of Jack’s work until I got started on the project. It was really exciting because it felt like a diverse mix, like three distinctly different voices to represent three movements.

How do you think your styles complement each other?

I think sonically we’re all operating from a different space, but more than that there’s some kind of cohesion. It feels like a more structured approach has been applied to each composer, rather than just a world of abstractions. Jack is doing something specifically looking at steam trains that would have been around in 1947, with lots of vocal samples from people travelling on those trains. I’ve got a more personalised approach, and Darren’s palate is more relating to the Indian sub-continent at large and he sampled a lot of sounds from traditional instrumentalists from the region. He’s going to be performing with Priya Purushothaman who’s a Hindustani classical singer.

You’ll also be working with visual artists Iain Forsyth and Jane Pollard. Combining music and visuals seems to be something that’s featured a lot in your work, why does it hold such an appeal?

There’s so much potential to tell a larger story when you combine those two worlds of media. I have a keenness to get into the visual world but it’s deep and very vast. Sometimes it just feels like the missing links can be filled very adeptly by the right visual component. I think from a performance perspective as well, unless you have a very playable piece of music with lots of instrumentation and musicians on stage, modern electronic music warrants a visual component so that people have space to get immersed, otherwise it has potential to be bland or unidimensional.

Different Trains 1947 will be performed at Edge Hill railway station in Liverpool on September 27, at The Barbican in London on October 1, and at Magnetic Fields festival in Rajasthan, India on December 17.

To find out more and book tickets, click here.