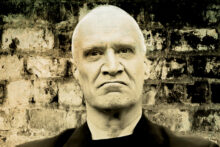

It always felt as if Douglas McCarthy had unfinished business with Essex. Though the Nitzer Ebb frontman spent his later years in Los Angeles, once he found out I was writing a book about the county, he seemed almost hell bent on telling me his story of growing up there. Those stories almost became a guiding light for my writing. It was the place that shaped him – I cannot separate Douglas from Barking, Canvey Island or Chelmsford, and Nitzer Ebb are a band that could only come from Essex. They might have started out sounding like a takeoff of the twinkly early Depeche Mode records in consort with the tougher sounds of DAF, but very quickly broke out into something more visceral and violent.

With his hair cut short but slick and long on top, and wearing shorts and a T-shirt with the sleeves cut off, McCarthy had the demeanour of the bad kid at school at the weekend, flick knife in pocket. On stage he was constantly moving, up for the ruck, accentuating the unhinged brutality of the band’s weaponised assault on the audience, as if to shake them out of their rigidity and small-cee Conservatism (this was Thatcher’s Essex, and their young peers were buying homes and settling into working class upward mobility).

Anyone who has danced to ‘Murderous’ and shouted “WHERE IS THE YOUTH” will know what power it has. In a sense it was a celebration of youth not being wasted on the young, as the patronising phrase goes. Rather, the youth would be wasteful, would expend their wants and desires, would cavort, enrage. That was the point: “Let passion spend / Let passion spend / Let your passion spend / Let your passion spend.”

McCarthy’s family had moved to Canvey from Barking, still by the Thames but in Greater London. His dad was a metal worker who had to get a coach all the way to the Isle of Grain on the Kent side of the Thames opposite Canvey at 5AM each day. He proudly told me about how his dad took part in a nine month strike over the requirement of protective clothing to use when handling asbestos. McCarthy Sr was a union member and member of the CND who left school at 15 and was “the most well read man I’ve ever met,” according to his son. “Politics was big in my family from an early age… all of us as a family would sit on a Sunday and read the Observer and the Sunday Times, and there would be classical music or jazz on,” he said. Douglas McCarthy’s politics were shaped by his dad. He was only 16 when Nitzer Ebb formed, and in early live recordings his voice was noticeably squeakier than it eventually became on record. There is some audio doing the rounds of an early gig in Chelmsford. Introducing ‘Violent Playground’, McCarthy, only 17, stands up to fascism: “At this point I’d like to make sure that no one makes the grave mistake of thinking we’re Nazis or fascists: because no one in their right fucking mind’s a fascist!” Given the violence that often erupted in their audiences, this was a bold move.

The McCarthys had moved out of Canvey when they feared eight-year-old Douglas had fallen in with the wrong crowd after they found him throwing stones at passing cars from the top of a bus stop. His life in a quiet cul de sac in leafier Danbury near Chelmsford was in stark contrast to what went before. McCarthy and his father would go and build rope swings or go birdwatching. The boy was seen as an outsider for having a thick East End accent, but the move led to him meeting David Gooday, Bon Harris and Simon Granger and forming Nitzer Ebb. McCarthy once said he couldn’t stand bands like Sham 69 who flexed their supposedly authentic working class credentials through posing as droog-like numbskulls. Instead, Nitzer Ebb wanted to subvert, escape and above all attack the supposed inevitability of their lot.

In a sense ‘Violent Playground’ is Nitzer Ebb in full biographical mode, describing their early days of being hated for their difference in a conservative Chelmsford scene: “We’re going out to play, there’s no fun at home / No one can stop us we play for real / We play for power.”

Douglas McCarthy linked the aggression that surrounded them to the displacement of the East End out to Essex. “Everyone had come in the late 60s as transplants from east London and Barking. I remember talking to my mates, wishing we were in London, like we were in this second-rate place, so we didn’t really care about it.” Later on, McCarthy and his mates grew up pursued by casuals “or soul boys as you called them then, who dressed in Pringle and jeans with a pipe down the side”. He told me about a theory he had about violence in Chelmsford being to do with its proximity to the Capital, so people wanted to still be seen as being “harder” than Londoners: “Everyone tried to ‘out London’ each other in terms of how they talked. I think it’s the weird geographical proximity to what was then a big bad metropolis – in the 80s the East End of London was rough.”

Even after the move to Danbury, McCarthy still returned to Canvey Island to go dancing at the Goldmine, a key venue in Essex’s jazz-funk scene, and Nitzer Ebb riffed on the disco of Sylvester, as well as the unrestrained nature of the Birthday Party and the darkness of Bauhaus. Theirs was a body music that took aim at the geezers who wanted to fight them on a Saturday night. Douglas said working class people like him who flirted with London and turned their backs on the Essex dream stoked resentment. “By looking like ‘poofs’ as far as they were concerned we had the potential to not forever live locally: ‘This is someone that is doing something different, I’m gonna punch them in the face.’” He told me how he would go down to an under-11s Saturday disco until it was closed due to a stabbing. “It was only later when I tell these stories that I think, that’s not right,” he reflected. “There was always violence.”

McCarthy’s dad used to drink with members of Dr Feelgood while his son sat outside in his maroon Ford Cortina, drinking shandies and eating packets of crisps, but he told me he held no fondness for pub rock. “Pub rock was the bane of our existence growing up and the first gigs we ever did in places like Crocs in Rayleigh, the Hermit in Brentwood, or the Res in Romford, we’d turn up to do a soundcheck with a foot tom, a snare drum, a cymbal and a Roland SH101 and the venue would be like: ‘When is the rest of the band turning up?’ They couldn’t understand it.”

In a sense pub rock and guitar music was foundational for Essex’s electronic wave. Alison Moyet started out sharing bills with Dr Feelgood with her band before Yazoo, the Screaming Abdabs. Depeche Mode’s early synthpop had its roots to the band’s earlier guitar-led iteration at the local Boys Brigade. Depeche’s Basildon became a minor Motown, a DIY pop factory started in the garage of a new town semi that prompted them to get out of Dodge. But Nitzer Ebb did something else entirely, managing to transmit the wanton, raging, violent place they knew on to records for all the world to hear. But I think Douglas McCarthy is up there with Wilko Johnson and Lee Brilleaux as a musician from Canvey island who so visually articulated so much of his situation and his biography with his body on stage. Where Dr Feelgood at their mid 70s height were like firing pistons in an engine, Wilko psychotically skitting forwards and back, Nitzer Ebb in their late 80s pomp were brutally physical. Gooday and Harris pummelled the drums as analogue synths rattled a militaristic sped-up motorik beat, with Douglas McCarthy simultaneously marching and writhing around the stage in a possessed frenzy in front of them.

Nitzer Ebb’s evolution took them to America where the Essex funk was joined by guitars, part of the mutual influence between the band and the likes of Nine Inch Nails. In recent years, though, Nitzer Ebb (and Douglas McCarthy in his collaborations with the likes of Terence Fixmer, Headman, Adult. and Cyrus Rex) returned to their tough electronic roots. Until he was forced to stop performing live for health reasons, McCarthy still retained the extraordinary energy that seemed part of his DNA, the son of a metal worker embodying the tension and release of the place that birthed him, the grit in the Essex synthpop pearl.