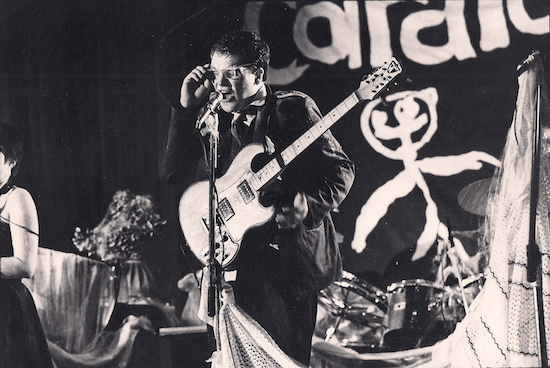

Tim Smith on stage at Surbiton Assembly Rooms in 1984 by Robin Fransella

Tim Smith, who finally left the planet after a lengthy spell of ill health, on the evening of Tuesday, July 21, was much loved, both for his hugely original music and his big personality.

Smith played his first gig as Gazunder, at Surbiton Assembly Rooms at the age of 16 alongside Adrian Borland (who later went on to found the underrated post punk band, The Sound) and drummer Bruce Bisland. A single, ‘A Bus For A Bus On The Bus’, was released in 1979 by an early incarnation of Cardiacs, then called Cardiac Arrest.

Early, cassette-only albums The Obvious Identity and Toy World emerged in 1980 and 1981, the latter being the first release under the new name, Cardiacs. The band’s own label, The Alphabet Business Concern, launched in 1984. That same year saw the band undertake a tour with Marillion, at the behest of vocalist Fish, who had seen them perform at the Marquee in London and had been “blown away” by the show. The majority of Marillion’s fans were less enamoured of the strange sights and sounds the support band brought their way.

From that time, until the late 90s, Cardiacs continued to release albums to a loyal following which also included many other musicians. Mike Patton, Steven Wilson, JG (Foetus) Thirlwell, Napalm Death’s Shane Embury, Blur and Alexander Tucker are just some of the names that spring to mind.

Cardiacs’ music is the classic ‘marmite’ proposition. People largely either loved or hated them. Whatever your stance, it’s impossible to argue against their originality and passion. Sounding in some ways like an Anglicised Devo, with elements reminiscent of Split Enz and the Residents, and a visual tip of the hat to the early works of David Lynch, Cardiacs are nevertheless entirely their own beast.

Despite an initially chaotic appearing veneer, their music is tightly structured and composed. Elements of punk, progressive, ska and psychedelia are all present, but for Tim Smith, it was best described as "psychedelic pop music". Another Smith project, The Sea Nymphs, with William D Drake and Sarah Smith, offered a gentler side of Smith’s creative output. A solo album was also released in 1995 and an album under the name Spratley’s Japs in 1998.

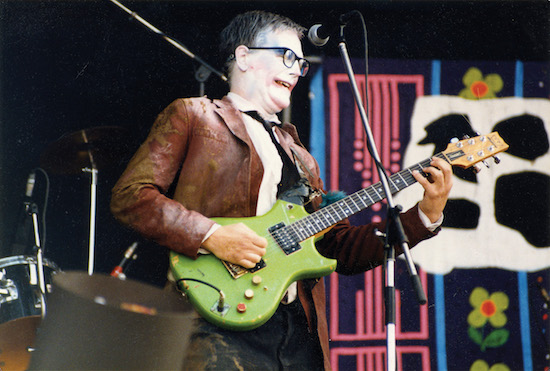

Cardiacs in 1988 by Steve Payne

It’s sometimes said that ‘you should never meet your heroes’ lest they turn out to be a disappointment. Whilst that may be true in many instances, it certainly wasn’t the case with meeting and becoming friends with Tim Smith when I first moved to London 26 years ago.

I was a huge Cardiacs fan when we initially met after a gig at the Krazy House in Liverpool in February 1992. I still have the T-shirt, with the moth and daisy montage from the cover of the ‘Day Is Gone’ single. I quizzed him about bands he liked. He talked about Henry Cow, whilst I went on about Can and Faust. When I moved to London to study English Lit at university, a little over a year later, I started bumping into him at gigs in Camden and we picked up the conversation where we’d left off. I discovered that we were, relatively speaking, neighbours. I was living in Archway and he was over in Crouch End. “Do you like drinking in pubs in the afternoon?” he asked. I told him that I did, and thus began many a long session, usually in the Kings Head not far from his flat.

I was a little in awe of him to begin with, but Tim soon put me at ease. He had a way of doing that. Very instinctually knowing the right thing to say to a person. “Being in a band is what I do, and that’s how we met,” he said. “If I’d been something other than in a band and we’d met, we’d still have been friends.” This was Tim all over. Highly emotionally literate, fun to be with, very funny, and a real one off, original character.

Detractors of his music have sometimes tried to paint it as ‘contrived’ or inauthentic, but the truth is that Tim was more like his music than any other musician I’ve ever met. (And there have been a few). That sense of wild-eyed wonder and big, heartfelt emotion that comes across in his work was Tim in a nutshell. That was exactly what he was like. That’s why so many people loved him, and why it’s so hard to write this now.

Cardiacs play Reading Festival 1986 by Jeff Green

Some of those drinking sessions went on well into the evening and occasionally I’d wake up on his couch, having followed up beers in the pub with gin in his flat afterwards. He played me early mixes of tracks from Sing To God, and even gave me a cassette of those. When it came time for the band to learn the new tracks, Tim sent me off to meet their guitarist Jon Poole and drummer Bob Leith with copies of that cassette.

When they toured, we would follow them around the UK, catching as many dates as we could. The band underwent a few line-up changes during the course of their history. Even though it wasn’t easy doing what they did for such a long time, Cardiacs always persisted.

Putting out their own records and arranging decent-sized tours across the UK, despite outright animosity from certain quarters of the music press, they kept on. It was what they did and nobody else did anything quite like it. I admired Tim enormously for that. Keeping going and being true to his own, weirdly out-of-step-with-everything-else but still pop-music muse.

I remember Kavus Torabi (who I became friends with around the same time) telling me on their last ever tour, how an agent had kept saying to them, “you’re going to have to scale this down, it’s too ambitious”, but when it came to playing the dates, the tour had been great success. I felt so proud of them all when he told me that.

When the news came through about his heart attack in 2008, we all kept hoping that Tim would, in some way, recover at least a little bit. We thought he had also suffered a stroke at the time, but eventually a diagnosis of a rare neurological condition called dystonia was given. Dystonia is caused by a lack of oxygen to the brain which causes involuntary movement.

Tim also almost completely lost his power of speech and had to communicate by picking letters out on a board. The neurological care centre he was first placed in, it only became apparent later on, wasn’t providing all of the treatment it should have been – later it would be closed down after a "damning" independent report deemed the home "inadequate". Tim first opened up about his health problems to the public in an interview he did with me for this site in 2018, when a JustGiving campaign was launched to raise £40,000.

He had been reticent for years about asking for charity and had some income coming in through sale of Cardiacs records and merchandise. When his place at the (hardly ideal) home he was in was threatened and he thought he might get moved to somewhere even worse, he finally agreed.

The amount raised quickly blew the target out of the water, and the national newspaper stories about Tim and an outpouring of sympathy from fans and fellow musicians felt timely and well earned. Many new fans discovered Tim’s music because of the campaign.

Later that year, Tim was awarded an honorary PhD in music from the Royal Conservatoire of Scotland. I had the great honour of giving the opening speech at a ceremony in Salisbury, where Tim picked up his doctorate. It was an enormously exciting moment for Tim to get some proper recognition, and for his closest friends to be there with him. I had been putting together interviews for a Cardiacs book, with Tim’s blessing. I felt doubly blessed in that moment, being given the opportunity to get to know my favourite band and then also to write about them after living through some of those times alongside them.

I had put the book on the back burner this year, but had just started thinking about returning to it a week or so ago. Then on Wednesday morning, I was preparing to line up a tweet about an interview with Voivod, when I noticed that guitarist Daniel Mongrain was wearing a Cardiacs t-shirt in the main image. I noted it was nice to see one again (they used to be everywhere, back in the late 80s/early 90s but you hardly ever see them today) to John Doran in the email exchange we were having. Ten minutes later I received a text from Jim Smith, telling me Tim had passed away the night before.

Despite Tim’s long-running illness, the news came as a massive shock. With the funding from the appeal, Tim was able to overcome a very difficult period that year and move to a place more suited to his needs. The last two times I saw him, he seemed to be improving considerably, due to the new regime (which he complained about nevertheless, as the physio really worked him hard). There was talk of him moving back to his home full-time, with a carer, of him finally being able to oversee the completion of their last album, LSD, which ironically was almost complete apart from the vocals that Tim could no longer provide. I had been worried about him catching Covid-19, but he had been tested for it several times and seemed to be OK.

In the end, despite fighting for so long, under conditions no one would want to think about, let alone actually face, it seems Tim went quietly of another heart attack while sleeping in his chair.

It’s tempting to rail against the unfairness of Tim Smith’s lot, but in reality, his prolonged illness gave him time “for so much respect and love to be paid to him and his music”, as Adrian McNally of the Unthanks (another huge Cardiacs fan) so kindly pointed out in an email he sent upon learning of Tim’s death. For those of us who knew him well and loved him dearly, it’s going to be a little while perhaps before we can separate the sadness of the current moment from the wonderful music Tim left behind.

Those recordings (and two live films) will outlast all of us though and will still be there whenever we want to revisit them. Writing this article yesterday, I found comfort in an unreleased track, called ‘Vermin Mangle’, which was supposed to be the final track on LSD. It’s a beautiful piece of music, initially serene and eventually epic. A little like Tom Waits’ ‘In The Neighbourhood’, with perhaps a touch of ‘Morning Has Broken’ and a wonderfully disorienting stereo effect that sounds like a brass band just climbed in through your window after slowly drawing close in the street outside. I hope that it, along with the rest of LSD, can somehow be released one day, but in the meantime, I can’t think of a better closing summation on a unique life well-lived than its opening lyrics:

“Think of a way, then always go your own way

Uncustomary evenings, legendary mornings

Louder than drums and softer than a cloud that’s been blown away"

We’re going to miss you Tim.