Around 1980 I was at my grandparents’ house conducting my weekly routine of sifting through my grandfather’s garishly and sometimes frighteningly illustrated and well-thumbed paperbacks when I came across Wheels Of Terror by Sven Hassel.

The book that belonged to my grandfather (who we called Pops) was emblazoned with a sepia photograph of a burning tank and tattered dead body of a soldier. It also had the bold and capitalised words, ‘THE BOOK NO GERMAN PUBLISHER DARED PRINT’. I was eight and, having already been introduced to horror and fantasy genre stalwarts such as Robert E. Howard and Larry Niven, I was hypnotised by the imagery and the unforgettably pulpish tagline:

“A NOVEL OF ATROCITY – as the tanks of Hitler’s Convict Regiment thunder into the inferno of the Eastern Front.”

I had no idea what the Eastern Front was, but was about to vicariously experience the hells of it for the first time. It would not be the last as, from that point onwards and up until I discovered Michael Moorcock a couple of years later (also thanks to Pops), Sven Hassel became my one and only reason to read and I tracked down the remainder of his novels. The rare power of Wheels Of Terror and his first, prototypical novel The Legion Of The Damned were not sustained by subsequent efforts that were undoubtedly and understandably churned out in a successful effort to exploit the public appetite for such books.

As they progressed they became disparate and episodic yet still maintained an energy, even the weakest efforts managing to convey a sense of emotional connection between the stalwart, apparently indestructible characters and the reader.

The wild success of Hassel’s novels did not go unnoticed and the late 70s saw the emergence of Leo Kessler. Kessler books are everything that a suspicious disdainer of exploitative war novels would assume Hassel’s work to be. Barely competently written pot-boilers that were superficial, image obsessed, humourless and in generally poor taste, Leo Kessler books celebrated the handsomely uniformed might of the worst of the Nazi war machine and reflected the worst instincts and obsessions of their author.

British war historian Charles Whiting churned out over a hundred of these dreadful books under the name Leo Kessler between the 1970s and his death in 2007, ensuring along the way that Sven Hassel’s novels, with their similar covers and marketing, rapidly became swallowed up by the turgid flood of these and other pastiches by genre novelists such as Shaun Hutson (writing under his dubiously named alter-ego Wolf Kruger).

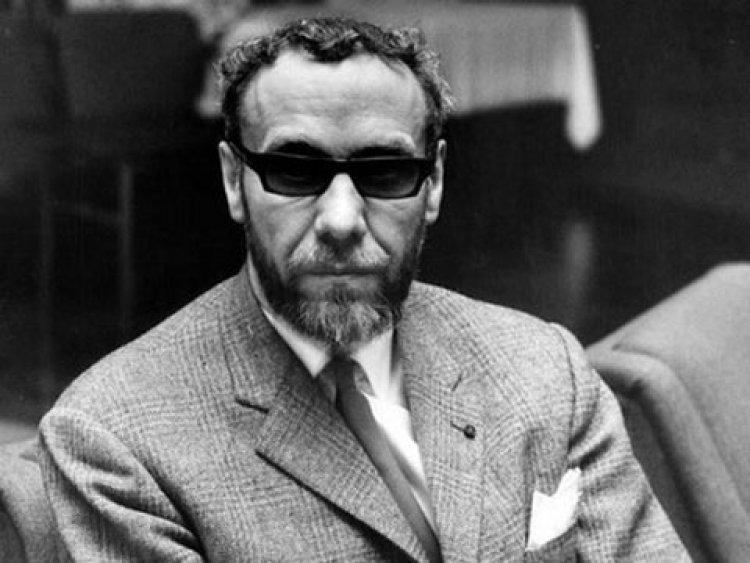

There may have been a faint note of poetic justice to this as Sven Hassel’s novels had themselves overshadowed the substantial works of former war correspondent Heinz G Konsalik and confirmed Eastern Front veteran Willi Heinrich, whose novel The Willing Flesh would later be filmed as, and subsequently retitled, Cross Of Iron. Sven Hassel was a pseudonym, and the Sven character, narrator of the books, an alter ego of the Dane Sven Pederson. Like Heinz G Konsalik and Willi Heinrich, Pederson lived through the war, but unlike those two the exact nature of his involvement in the conflict has been the subject of debate.

His harshest critic, Danish journalist Erik Haaest, has argued ceaselessly that Pederson never left Denmark and his only service was as a member of the much hated, Nazi supporting police force. As the credibility of this Haaest himself has been brought into doubt due to his holocaust denial the mystery around the real history of Sven Pederson will remain unsolved, although the numerous technical inaccuracies inherent to his tales do betray him somewhat in the eyes of history buffs and WW2 hardware nerds.

Nevertheless the novels of Sven Hassel are compulsive page turners and were in no small part responsible for an acute re-evaluation of the nature of the German soldier in the minds of a voracious readership, particularly in the 1950s and 60s. At that time the power of his descriptions of not only atrocities, but also the daily hardships of the Eastern Front charnel house, also struck a chord so far un-plucked by novelised accounts from allied soldiers turned authors. In the case of his second book Wheels Of Terror the very first chapters detail first-hand an experience of the fire-bombing of a German city by the RAF that lives long in the memory. On his experience with Hassel’s book British writer Alan Silletoe, author of Saturday Night, Sunday Morning and The Loneliness Of The Long Distance Runner wrote:

“This is a book of horrors, and should be left alone by those prone to nightmares. Sven Hassel’s descriptions of the atrocities committed by both sides are the most horrible indictments of war I have ever read.”

Critic Alistair MacRae had a similar reaction:

“It may be that this is a book that will make you sick. If so, my advice to you is to read it and be sick, for such sickness is humanity’s only hope for a sane and healthy world.”

Time, criticisms, deconstruction and another twelve increasingly diluted novels may have reduced the literary and historical credibility of Hassel’s novels but their graphically violent covers ensured their discovery of a new generation of readers in the 1980s. The cover of Court Martial is often quoted by fans, and even by people who have never read Hassel, as standing out so eye-poppingly from the other books in their local newsagent that buying cola cubes instantly took on a more harrowing dimension than when that rack space was occupied by Doctor Who And The Giant Robot only a week earlier.

To this day I never cease to be impressed by the number of other men of my generation who were touched one way or another by the books of Sven Hassel. Even more impressively I worked with a chap a number of years ago who would become a close friend over time. Although English Alan has a Danish father, speaks the language fluently and lived in Copenhagen for many years. Inevitably the subject of Sven Hassel came up one night when we were severely worse for wear and Alan said, quite blithely, ‘Oh yes, he’s well known in Denmark. My dad says he used to go the same swingers’ club.’

Casual car key swapping antics aside, sensationalism and marketing were only partly responsible for the longevity of Hassel’s appeal. It was his grip of adventure writing and sharp characterisation, a dark streak of gallows humour and a talent for brief but vivid descriptions of extremely harrowing events that made the books live up fully to those lurid covers. In addition Hassel created, in the forms of Joseph Porta, Tiny, Julius Heide, The Legionnaire and The Old Man, a truly memorable, vicious, hilarious and deeply human band of misfits that resonate with readers all over the world and, in my case, over 25 years after I last picked up one of his books.

When I heard of his death I picked my old copy of Wheels Of Terror from the shelf, the very same one that my Grandfather gave me over thirty years ago, and re-read the first two chapters. Now I have to read it all. Thanks Pops.