Steven Wells 1960 – 2009

=========================

David Stubbs:

So, this would have been the late 90s. I was working for the NME at the time. I’d just answered a call in one of the cubicles in the male bathrooms and, duly relieved, hands washed and dried, mirrors checked for eyebrow dandruff, had returned quietly to my work station. A minute or so later, another figure exited the bathroom and re-entered the office – I’d been aware of someone in the cubicle next to mine. He did so, however, rather less quietly. "David!" he boomed, fixing me with that unwavering glower of his, "You use far too much toilet paper." I’d no idea I was being monitored. I didn’t think I’d been excessive; Steven Wells, however, begged volubly to differ and left no one in any corner of the large, open plan NME office that he did so, delivering me a short and public sermon on the subject. I can’t remember the gist of his argument – I was too busy fighting down a burning sensation in the cheeks – but I believe he may well have linked my supposed profligacy with the Andrex with my vegetarianism, something else he despised with Orwellian fervour. I think he suspected that if the workers were to rise up, they would better to so fortified with steak pie than lentil croquettes.

It wasn’t the only time he took me to task. Another time, it was for a pink shirt I was wearing, which he considered compromised and in some way counter-revolutionary. Another, it was for having expressed a kind word about the despicable Radiohead; on yet another, for being "public school". I didn’t go to public school, as I repeatedly informed him, but to no avail. Everything about my behaviour was public school, so that settled the matter. On each of these occasions, as I thought what I thought every time I encountered the guy; Swells, you rotten, baldy, cheeky, brilliant, funny bastard, every time I meet you, you never fail to cheer me up.

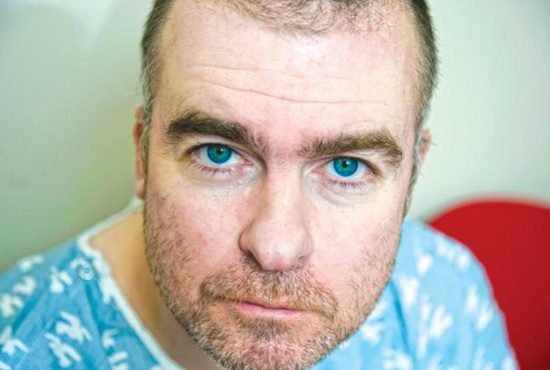

Swells was one of those journalists who are the equal of their writing selves in real life. Having started life as a ranting poet, there was an oratory quality about his prose – spittle-flecked, but with a wonderful, inimitable sense of rhythm and meter, especially in his adjectival rifle fire. Being addressed by him was like being repeatedly but painlessly headbutted. However, to know him in real life was to discern unmistakeable qualities which sometimes those only acquainted with his relentlessly polemical and provocative prose could and often did miss. They were, a nurse said of him, in his eyes, the most beautiful she had seen. It was evident in the last published photo of him. [Published above – Ed]

Direct, unblinking, challenging, inquisitive, but also mischievous, kindly, humane, endlessly willing to engage. Disliking this person would be like disliking the youthful Muhammad Ali – there’d have to be something wrong with you. Swells was, as many have noted, more than just a music journalist. He was more like a force of nature, crashing over whatever his subject matter might be with all-sluices-open gusto. He was, by the same token, less than a music journalist in some respects. James Brown, in a thoroughly appreciative reminiscence in The Guardian, spoke of him having "no real interest in music", which undoubtedly contains some truth. He inevitably excited criticism, even among his admirers. He drew up crude, binary, "Dennis The Menace versus Walter" oppositions. Self-doubt, nuance, epiphany, qualification were all conspicuously lacking in his writing – it was as if he’d made up his mind about everything in 1981 and that was that, bang, bang, bang, Swells, Swells, Swells all the way through, paragraph in, year out. Listening, some argued, was not his forte. Read one Swells piece, read them all.

He was accused of a hectoring, even bullying tone, the stentorian ranting of an old Marxist dinosaur. Certainly, Swells was limited in the chords he bashed. In later years, the opposition he set up was along the lines of feisty, Britney girl pop=good, miserabilist indie = bad – a sadly too common attitude prevalent in some corners of the music press, which has strangely never been short of those labouring under the belief that the weekly inkies should turn into the late Smash Hits, a policy which, when adopted at Melody Maker, led to its demise. However, it is simply impossible to dismiss Swells as an unreconstructed ex-punk bonehead or a one-note contrarian. Sure, the chords he played were limited but it was what he extracted from them that counted. You might have known what was coming with a Swells piece but his swarming, jabbing energy, his ability to tap the language again and again for permutations as refreshing as a cold bucket of water, left you tickled pink, gasping for air, raising a finger to say "Yes. But…" before helplessly giving up.

As those who knew him will attest, Swells was ebullient but no bully. His formative years in West Yorkshire, some spent working on the buses, would have brought him into contact with enough obnoxious male types for him to develop a lifelong loathing of overbearing thuggishness, and it was fascists or marauding "Tetley Bittermen" against whom he railed in his spoken word poetry. As for his Marxism, some would argue that the End of History put paid to all that, and that the "real" world is "more complicated" than his antiquated leftism could ever allow for. Hence, his proposal in one of his later sports columns to nationalise the English Premier League could be condescendingly dismissed as fanciful drollery.

But you know what? Suppose he was right? Suppose society ought to be organised along a "from each according to their ability to each according to their needs" lines? Suppose those who scratch their chins doubtfully at such long-held tenets aren’t folk in the process of devising an even fairer and better ideal for living but are merely the sort of trimmers, hemmers and hawers, vacillators, defeatists and compromised do-nothingers who, skulking in the twilight of nuance, qualification and self-doubt quietly ensure that the other side always seems to win?

None of that for Swells. For him, his terms were long defined, the ultimate truth was blunt and direct and his job was to deliver it as such in an endlessly inventive way, whether discussing pop, wanking, The Dead Kennedys, washing machines, the NPL, excessive toilet paper use or pink shirts for that matter. (NB, Swells was no homophobe – he reserved a special circle of scorn for gay bashers in his rhetorical inferno).

Because, simplistic as Swells’s antipathy towards, say, Radiohead or The Smiths was, there was in his objections, his mocking wind-ups, a kernel of truth. He was probably not wrong to be wary of the ostentatiously enervated and morose likes of Morrissey and Thom Yorke, who for all the good they might have done arguably encouraged a fey, wan, snivelling fainthearted life-denial in their listeners. He once described Belle & Sebastian as "self-loving, knock-kneed, passive

aggressive, dressed-up-in-kiddy-clothes, mock-pop-creepiness peddling, smug, underachieving, real-pop-hating no-talents celebrating their own inadequacy with music so white it’s translucent". Not all of those brickbats land true but enough do to guarantee the belly laugh. He once memorably took Sonic Youth to task in an NME interview, dismissing Thurston Moore’s extensive record collection as evidence of "a mild form of autism" and generally delivering a jolt to the midriff of these ageing, heavy-eyelidded denizens of the "daydream nation" they could scarcely have anticipated after years of genuflection from the inkies. You didn’t have to hate Sonic Youth to love it but it was probably necessary to agree that they had become tastefully shrouded in unexamined complacency over the years in order to. No daydreaming for Swells. If anything were ever to change, if we supposedly of the radical cultural left field were actually at all serious about wanting to effect social transformation, it was going to require the sort of eyes wide open, vein-pumping, endorphin-driven, life affirming energy of which Swells was a daily, personal exponent.

Was he right or wrong? Whatever, we’re all the worse off for him no longer being around to pump up the argument. It’s a cruelty those who knew him have dwelt bitterly on this past day or so that someone capable of lighting up a room in a power cut, so cheerfully seething

with life, so sociable (with the wan life-deniers as much as anyone), so willing to share and expound ideas, should have had his own life so cruelly curtailed so stupidly early. Will we ever see his like again, some have asked? It’s impossible to imagine the music press playing host to another Swells, and, of course, the last thing we need is some sort of Green Day-style imitation. But he leaves a legacy and a blazing example. And so much unsaid. That’s what’s so sad. He had so, so much more to say. Restless In Peace, I hope…

Andrew Mueller:

IN the late 1980s, before I became a Melody Maker writer, I was a Melody Maker person – as opposed, obviously, to an NME person (not that there’s anything wrong with that, live and let live, some of my best friends, etc). However, and I’m certain I wasn’t alone in this furtive treachery, I also bought the NME every week anyway, because Steven Wells wrote for it. This

was a considerable accolade: I lived in Sydney at the time, working for an impecunious street rag, and air-freighted UK music papers were not cheap. Swells always repaid the investment, though. His scabrous invectives, giddyingly inventive swearing, and confrontations with clearly bewildered musicians struck me then, and strike me now, everything that rock writing – indeed, any writing – should aspire to be: smart, funny, provocative, unreasonable, unpredictable, uncompromising and always, always suffused with an incandescent joy at the possibilities of language.

The first time I met him I was, naturally, utterly petrified (I’m pretty certain I wasn’t alone in that, either). It was 1990, and I was on one of my very first assignments for Melody Maker, reviewing a gig – The Wonder Stuff and Ned’s Atomic Dustbin (so help me), at Barrowlands in Glasgow. Swells was covering this auspicious occurrence for the NME. We found ourselves sharing a taxi to the venue. To either or both my terrified delight and delighted terror, Swells in person was exactly like Swells on the page, a hyperactive torrent of opinions, ideas and expletives. I fretted, probably with reason, that he regarded me, probably with reason, as a clueless milquetoast.

Later that night, though, back at the hotel, he accosted me in the bar and delivered another bug-eyed monologue, punctuated with hearty, bruising prods to my ribcage, to the effect that he’d been reading what I’d been writing, that I was doing quite well for an Australian parvenu barely of legal drinking age, and to keep at it. Over the years, I’ve heard variations on that story from dozens of other hacks and musicians: for all that Swells was caricatured, not least by himself, as a cynical, scattergun curmudgeon, he was essentially a believer, and an encourager.

I cannot claim, to my regret, to have known Swells beyond the occasional drink and argument when we happened to be reporting on the same event, but when I first heard he was ill, I wrote to him, enjoining him to regard his disease as if it were a winsome, twee, enragingly effete indie band. It was, on reflection, a poor choice of rallying cry, cancer being as obdurate and indefatigable an opponent as mediocrity.

Judging by his brilliant chronicling of his illness, however, he refused to regard either foe as insuperable. It would be something to be able to believe that his passing might prompt a large-scale revisiting of his best work – and with it, a reinvigoration of the idea that rock writing can be so much more than box-ticking, consumer-guide hackery, doing nought but reassuring that all music (and all literature, all politics, all art) is, you know, pretty good if you like that kind of thing.

As I write this, the internet fizzes with uncountable tributes, and it’s telling that those from people who didn’t know him sound as bereft as those from people who did. Good writing – writing with a heart, writing with a brain, writing unfettered by fear of giving offence, writing that credits the reader with intelligence and curiosity – can change lives, and Swells did. I struggle to recall him ever expressing an opinion with which I agreed, or championing an artist whose music didn’t make me envy the deaf. But I’d always read him, because he wrote stuff that made people laugh, and made people think, and that’s not as easy as he always made it look. Salut.

John Robb:

Who’d have thought the cancer would have taken Swells. You would have thought it would have been terrified of its machete-mouthed, acid-tongued, brusque, neo-skinhead host and legged it – cowering in a corner as the rage induced spittle of Swells turned upon it.

Fuck that mean disease. Fuck it.

I’d known Swells since 1983. Quarter of a century since he turned up at a Membranes gig in Birmingham and did his ranting poet bit. He was cocky, offensive and in your face and that was before he even got on the stage. He spent the rest of the night being argumentative, antagonistic, smart and dangerous. Everyone in the room hated him instantly. I saw a fellow traveller, and bought his Molotov Cocktails fanzine.

He always gave the Membranes good reviews which probably helped to totally fuck up our career but they were eminently readable rage of consciousness attacks from those far flung days before the accountants came in and told everyone to behave. It was a time when freelancers were, well, free and were allowed to be themselves and rage against the zeitgeist like Xerox guerillas from fanzineland.

Swells was the first of my mob of roots punk rock yob orators to get on the music press. And our paths would criss cross over the years. He hated loads of bands I loved and sometimes didn’t seem to like music at all. Whatever he said he said it well and he wrote genius wild copy with adrenalised abandon and wound the readers up with the sort of rage that we had bought into punk rock for. Even his recent Guardian blogs brought the same sort of reaction but the writing was always perfect. The rant as a work of art.

We once both went on a trip to America to do a feature on Waxtrax records in Chicago and argued for three days about music, punk rock, America and life. It was a brilliant time. He carried a clipboard and a pen with him everywhere on that trip because he was a ‘professional’ I noticed that he didn’t write a word down for the whole three days that we were there.

He made a video for Goldblade for one of our late 90s singles when he briefly gave up music journalism in favour of filming bands. He made a homoerotic masterpiece where we were stripped to the waist, covered in wallpaper paste and dancing like fools. It was a work of art.

I knew he was ill and emailed him. He would send terse rude answers back. That was perfect. Because despite his bluff, white rose, in-yer-face, challenging journo monster personae you knew he was a sweetheart.

And whatever you thought of what he was trying to say at least he sounded like he was alive.

And that’s what makes his death so fucking sad.

Sarah Bee:

Steven Wells was a proper fucking music journalist; he answered to no-one and pandered to no mode of thinking. He was utterly unconcerned with cool bullshit, impossible to influence – you could always trust that he loved what he said he loved, hated what he said he hated, and gave not a fuck who disagreed. There was no posturing or pretention in his writing – in a purplish landscape of frill-shirted fops he was a rock of straight-up righteousness.

There was a charge of positivity in even his most lavish befouling of his least favourite band – an underlying urgent message to the rest of us that if you’re going to dislike something, don’t fanny about, pile in. Everything he wrote would take a point or an idea and hammer it until it whimpered, and he meant it – it was never just for the fuck of it (except that it was totally and completely for the fuck of it, always – for what Don Logan in Sexy Beast called "the sheer fack-off-ness of it all"). The thunderous vigour of his stuff made it magnetic – you’d be innocently trying to read some gentle musing on something you liked at the top of page 21 of the NME, but your eye would be helplessly drawn to the foetid bottom corner of page 20, where Swells was herding galloping shitcocks and fuckswine to violently trample something you’d never heard of.

To the untrained eye it might look like someone had poured a load of pellets into a swear gun and merrily blasted away at a wall for a few hundred words, but make no mistake, there was a bulldozing intellect behind the fuckingfuckery. It infused and elevated the swearing. When Swells swore it wasn’t in the feeble, neutered way the rest of us swear – it was a hearty monolithic kind of swearing that beat profanity down until it became poetry.

Some got tired of what they saw as the same old Swells schtick – but he was the kind of writer who put everything into whatever he wrote, from the gobsmacking piece he wrote for the Philadelphia Weekly on his Kafkaesque experience of hospital, to the throw-away-ing-est little 200-word snort about some forgettable album. If it seemed one-note to the casual reader, it was because it was a constant full-on horn-section blast of thought and personality that never faltered. He loved words, never tired of them, and the heresy of sometimes making his subject matter act as a gimp to serve his evil prose was disgustingly fun to observe. And that kind of muckily elegant dicking around only served to emphasise how skilled he was at crafting and steering an argument when he wanted to. He knew what he was on about and how best to display it, but most of all he knew how to convince. There was a sincerity there even when he was fucking with your head for laughs.

Swells brought an equal force of barrelling glee to bear on the stuff that he loved as to the stuff he wanted to eviscerate, and he spread pogo-ing enthusiasm as liberally as he poured lurid piss. He had a spectacular, effervescent intelligence, and although he claimed to have a rampaging ego he was far more interested in bolstering and bigging-up others whom he believed in. He was exactly like his writing and nothing like it at once – always eager for an argument, more open-minded than you’d think, never afraid to show his big squishy heart.

It’s preposterous that Swells is dead. The pure incredulity felt by so many on hearing of his death must be a measure of his stature as a writer and as a bloke. Start missing him now, and get used to it, because the boots that have just been vacated are never going to be filled.

Besides which, his favourite word was "shat".

Ben Marshall

No doubt I won’t be the only one to remember June 25 2009 as a strange and melancholy day. It began with the news that the most famous of Charlie’s Angels, Farrah Fawcett, had slipped away, killed by cancer, still looking strangely as she had done all those years ago when she donned a red bikini and became the best selling pin-up girl of all time. As a child, I had that naff, alluring, iconic poster hanging on my wall. So did everyone of my generation. As the day was ending, we learned of Michael Jackson’s death. A pretty girl from the MOBO awards said that everyone will remember where they were when they heard of Michael Jackson’s death. It was she added, no doubt accurately but nonetheless vapidly, a "Diana moment, a Kennedy moment."

At some point between these two headline-grabbing events, I heard that my friend Steven Wells – Swells to everyone who knew him – had died. Late last night a hysterical and slightly profane thought about Swells’s impeccable sense of timing crossed my mind, and with it the vivid sense that Swells was never afraid to take on the big guns. The King of Pop and The Blonde Bombshell? No problem. Swells was wonderfully confrontational. His journalism was furious and funny. His stage name, Seething Wells, made a witty, angry pun on his given one. The video production company he ran alongside Nick Small was named Gob TV. His publishing company, called simply Attack, printed books by the communist skinhead Stuart Home. Sample title: Whips & Furs: My Life as a bon-vivant, gambler & love rat by Jesus H. Christ.

Perhaps inevitably, he has been described by some as a bully. Swells did undoubtedly show no mercy to the weak; but then he showed none to the strong, either. If he picked on someone, he did it not because they were weak (the definition of a bully), but because they were, in his eyes, wrong. If Swells thought you were mistaken about something – say, the exact date when The Clash sold out, or the true meaning of French Revolution, or which was the best Daphne and Celeste single – he would let you know in no uncertain terms, and he didn’t give a toss about how big or small you were.

Yesterday I scribbled something on Facebook about Swells bracing cynicism and his infuriating ability to make me laugh out loud at my most cherished beliefs. Many people in their forties who express disgust at others or at the world wind up sounding jaded and Pooterish, but Swells’ contempt came at you like the cleansing blast of an icy gale. It was exciting to read his tirades about Tories, Smiths fans or, lately, the Premiership; and even more exhilarating to hear these opinions expressed in person. But then Swells’ righteous anger was always underpinned by an unflagging, ebullient optimism about people and the world in general. He was without question a practiced hater, but equally he fuelled himself and ignited others with his idealism.

I remember once arguing with him late into the night about how hopeless his socialism was. People I declared, simply weren’t up to it. Swells shook his head and began citing a myriad of different incidences when people behaved with natural altruism. Like so many of our arguments, I came away from it feeling that much happier. As almost anyone who met him will testify, it was impossible to be bored in his company. It was also hard not to feel good, even after an expertly crafted tongue lashing.

This idealism made him a part of an increasingly rare group, the professional writer who refuses to compromise either his style or his opinions. Almost all newspapers and magazines have some house style and if a writer wants to pay the bills he had better learn what that style is and cut his cloth accordingly. The problem with doing this is that you end up producing serviceably anodyne prose and in the process forgoing and forgetting whatever style you had in the first place. Swells never had that problem, the things he was writing toward the end of his life – be they the wonderfully witty meditations on the disease that would eventually kill him, or his brilliantly convincing argument that Gordon Brown should nationalise The Premier League – were as fresh, funny and angry as anything he wrote for the NME back in the 80s.

Swells final piece for The Philadelphia Weekly ended thus: "I blame it on sunshine. I blame it on the moonlight. I blame it on the boogie." Words culled from a Michael Jackson song days before The King of Pop’s own heart attacked him. I will miss Swells painfully. And I not only have to admire his sense of timing, but wonder at what appears to be some kind of instinctive prescience. He chose no ordinary life to live, and happened upon no ordinary day to die.

John Doran

On Friday I gave up trying to write about Swells, lost in a maze of tolling bells, stopped clocks, super bright candles that burn your eyebrows off and headed to a job I had in the evening – DJing to a car park filled with 600 lager-marinaded AC/DC fans in Wembley.

It was an enjoyable afternoon dropping classic rock and metal to a bunch of people demented with excitement at having their tri-yearly day out without the kids. But half-way through a particularly good run (‘Down Down’, ‘Suffragette City’, ‘Jailbreak’, ‘Problem Child’) a dark

cloud passed through me. ‘What would Swells do?’ asked the stupid part of my brain. ‘I’ve no idea’ said the honest part.

I stopped AC/DC mid track and immediately everyone started booing. After some fumbling with my lap top I shouted: "Fuck Michael Jackson but fuck you even more if you don’t like this. This is for Swells" and played ‘Rock With You’ by the recently deceased King Of Pop.

Immediately two guys started charging toward me. One with a gold tooth, a park tan, an iron cross and the T-shirt of a skeleton flipping the bird reached me first and got me in a headlock.

"Fucking brilliant!" he screamed into my ear. Even from my bent double position I could see the crowd had split into the disco dancing and cheering and the beer throwing, booing and marauding. Without letting go of me he turned round and floored the other guy who was obviously less enamoured with the temporary interruption to the feel good blues rock of the day.

"Fucking brilliant! Now play some ABBA." He could see that I was about to say no and said: "You will play some ABBA, you will dance with me.We will go mental. Properly fucking mental. And if you don’t I will kick the fucking shit out of you."

"’Does Your Mother Know’ or ‘Dancing Queen’?" I asked. You’ve probably gathered by now that this isn’t a metaphor but just some stupid things that happened in sequential order. But there was a brief moment where dancing, booing, fighting, drinking, ACDC T-shirts and pop disco combined in some new disharmonious art form. Disco man and rock man laid into each other and went careening into the sound gear and only stopped when they buckled a stand causing a large speaker to fall on them and knock them temporarily senseless.

When order was restored with Boston’s ‘More Than A Feeling’ I felt dark again. Swells at his weakest was ten times braver than me at my strongest. I couldn’t even imagine what he would have done or if he would have been there in the first place. But if he was he certainly would have had the sense to play Daphne and Celeste instead of Jacko. And it would have ended up in a conga line with him up front leading it like a psychically diverse Marxist pop rock Colonel Kurtz.

When the manager came over to ask what had happened I told him that I was blaming the damage to his equipment squarely on the boogie. He was an inspiration you see. Not just in writing, which doesn’t always matter that much, but in day to day stuff, which really does.

Daniel Lane:

While commissioning features at Metal Hammer back in the early noughties, I got Steven to do this regular feature called The Spanish Inquisition. Basically, every month we’d get a bunch of reader questions e-mailed in and he’d put them to some of rock’s most fearsome individuals in his usual deadpan fashion.

There’d be some really inane questions in there, as you’d expect, but, for some reason one person would write in every time and ask Swells to find out if that month’s subject was secretly gay. I think it came more from the desire to see if they could get Swells into a punch-up rather than finding Rob Halford a date with similar interests. Anyway, after each interview, Swells would come back into the office unscathed and full of beans, and the rock star in question would remain either in the closet in denial or would simply have been a raging heterosexual.

My favourite instance was the time Swells said to ex-Black Flag frontman / actor / comedian / author / publisher / radio host / TV presenter / body builder / misery guts Henry Rollins something like: "Being a strapping young lad, you have a lot of fans within the gay community. Have you ever taken any of them up on the offer of a date?"

To which Hank replied:

"First I heard I killed someone, then I heard I wanted to kill myself and now you’re asking me if I’m gay? How can I go from being homicidal to suicidal to homosexual?" And to this day, that remains my favourite all time rock star quote of all time. RIP Swells, you mad old bastard.

Alex Burrows:

Swells’ attitude and appreciation of proper punk and politically militant bands made him stand out as an NME writer in the early 90s for me. So when the chance arose, I talked the Editor of Metal Hammer into hiring him as a freelancer in the early years of this decade. One of the first times I met him in the flesh was for the original photoshoot for Metal Hammer‘s ‘Spanish Inquisition’ cardinals. Naturally, Swells insisted on wearing the flying helmet and oversized comedy RAF moustache. During the shoot he disparagingly called me "an accountant" (just because at the time I processed his invoices as well as his copy) with his usual biting acerbic wit. It was typical of his technique: be confrontational first, ask the questions later. And that’s what made him such a great writer. In an industry currently over-crowded with sycophants, yes-men and record label whores masquerading as music journalists, we need his type now more than ever. Oi, Swells: rest in FUCKING peace.

Terry Staunton:

The NME office in the mid-1980s was a curious place. Warring factions, essentially the indie kids versus the soul boys, furtively gathered in corners, attempting to scupper each other’s hopes of securing next week’s cover. The battle to get either a Shop Assistants B-side or a Steve ‘Silk’ Hurley remix onto the turntable was nothing less than the journo equivalent of sticking a flag on top of a mountain.

Slicing through these often petty and pointless face-offs was Steven Wells, aka Swells, aka "punk poet" Seething Wells – a fiery individual whose first pieces for the magazine were published under the by-line "Susan Williams". He had little time for cliques; rather than nail his colours to any one musical mast, he was more likely to smash the masts into toothpicks.

If ranting and radicalism were Olympic sports, Swells would have been Steve Redgrave, but the near caricature of that image does him little justice as a writer, as a man. Yes, you might have found him waving a copy of the Socialist Worker at any one of a dozen protest rallies, but he’d also take time to pore over the Smash Hits! crossword, or make jokes about musicians he clearly loved but realised were ripe for parody. He once suggested, in pitch-perfect Barking vowels, that Billy Bragg should release an album called More Songs About How I Neffer Git To ‘Ave Any Sex.

Page Five was a valuable spot in the NME in those days, more often than not given over to a single, short feature covering a wider brief than the rest of the magazine; newsworthy and not always restricted to music. Swells instigated dozens of them, such as an aggressive grilling of anti-smut campaigner Mary Whitehouse, or the proliferation of skinheads in TV advertising (Persil, Weetabix, The Guardian), and the quality of his writing, the forcefulness and persuasiveness of his arguments, his sheer articulacy, left the rest of us gobsmacked and lamenting our own journalistic shortcomings.

The arrival of Alan Lewis as editor in 1987 signalled a change in NME‘s editorial policy, but Alan was savvy enough to realise that Swells was one of the title’s top writers and should be cherished. The notion of one-hit wonders T’Pau as cover stars raised a few eyebrows, but Swells delivered a brilliant and thought-provoking piece on the superficial nature of pop stardom that could have come from the pens of Greil Marcus or Lester Bangs.

Time in his company was time well spent. At the end of my first day at the NME he invited me for a drink in the West End, but not before we’d dedicated the best part of an hour to scraping fascist posters off vacant shop windows. My favourite memories of Swells, though, might be the day IPC’s health and safety officer made him blush by demanding to inspect the scuzzy sweatpants he’d apparently worn to work every day for a month, or his incessant cheating during a late-night Scrabble session at my Muswell Hill flat – which prompted fellow player David Quantick to remark "if we leave him under a pillow, maybe the prat fairy will take him".

Musicians loved him, including many for whom he had few kind words. To be lambasted by Swells in print – or, better still, face-to-face – was seen as a badge of honour, as much a rite of passage as a Peel session or brief turn on Top Of The Pops. He made a handful of enemies along the way, but they were a sad minority compared to the thousands who ached to be his friend. I’d like to think that I was his friend, and I have been aching terribly since his passing.

Read more tributes to Swells from Everett True, Charlie Brooker, David Quantick and Los Campesinos.