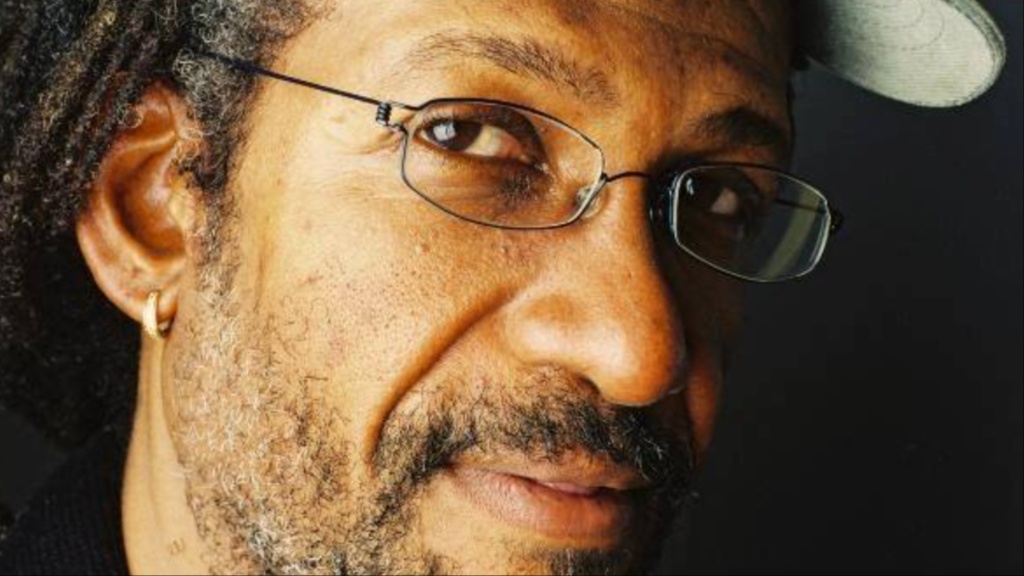

It was at the school gates, while picking up a KPop Demon Hunters-obsessed five year old, where I heard the sad news that Sly Dunbar had left this mortal coil yesterday. This may seem like the last place you’d expect to find out about the passing of reggae’s most enduring drummer and, alongside bassist Robbie Shakespeare, one half of the most prolific rhythm section in show business, but such was Sly’s reach, his music permeated pop culture, supplying the back beat for everyone from Bob Marley to Bob Dylan.

I was my daughter’s age when I heard Dunbar on the drums for the first time. A downbeat one-drop bopping behind the aching falsetto of Junior Murvin. Those scattering hi-hats channeled through Lee Perry’s ear splitting ring-modulator, and snaking out of our tiny TV speaker as ‘Police And Thieves’ throbbed from the Top Of The Pops studio into our living room on 22 May 1980. This was just shy of a decade after Sly recorded drums for the Dave & Ansell Collins single ‘Double Barrel’ which scored them a UK top 10 in the Spring of 1971 when the drummer was just 18.

Born Lowell Fillmore Dunbar in Kingston, Jamaica in 1952, he was bitten by the drumming bug in his early teens after witnessing Lloyd Knibbs propelling the accented backbeat rhythm of The Skatalites. He quickly progressed from bashing pots, pans and tin cans, to joining his first group The Yardbrooms who backed saxophonist and Skatalites founder Tommy McCook in 1968, and proto-MC Dave Barker on his crossover dancefloor hit ‘Funkey Reggae’ in 1970.

Sly, in fact, gained his nickname due to his love of funk and soul. Aside from following homegrown drummers such as Knibbs, and others present at the birth of reggae including Carlton Barrett and Santa Davis, Dunbar was enthralled by the laidback beats of Al Jackson Jr. which could be heard on Al Green and Booker T. recordings, and especially the syncopated soul stew of Gregg Errico with Sly & The Family Stone. It was during a short stint with a hotel band in Jamaica called The Volcanoes, that band leader Linford Harvey got tired of the drummer listening to Sly & The Family Stone, remonstrating “Anything but Sly, Sly, Sly!” In a 2008 interview with Benji B, Dunbar asserted “Sly’s the boss. So everything I did, they called me Sly. When I got back to town, it stuck.”

Another major influence from beyond the realms of reggae was his love of Philly soul, particularly the smooth strains of jazzy disco coming from the Philadelphia International label in the mid 1970s. While working with studio group The Revolutionaries at Channel One, Sly spent a couple of years perfecting the crisp and spacious drum sound which would quickly become his trademark on records like ‘I Need A Roof’ by The Mighty Diamonds. The already prolific bassist Robbie Shakespeare was working nearby with Bunny ‘Striker’ Lee’s studio group The Aggrovators when he was tipped off about the Channel One drummer. Shakespeare instantly recommended him for a session, and soon after Dunbar was laying down a pumping steppers beat alongside Shakespeare for the ‘Striker’ produced ‘I Forgot To Say I Love You’ by John Holt.

Sly & Robbie were almost inseparable from therein, establishing a new and sought after sound, championing the rockers beat with a heavy emphasis on Sly’s snares cracking around a pounding kick drum. Everyone wanted a piece of the action, especially Peter Tosh who had recently split with The Wailers and was lighting up international stages after his solo debut Legalize It. The trio adopted the name Word, Sound & Power in which Tosh handled the words, while Sly & Robbie delivered the rest, and they caught the attention of The Rolling Stones while Jagger and Richards were visiting Jamaica.

Tosh’s 3rd LP came out in 1978 on the Rolling Stones’ own label, and the group were invited on the Stones’ tour that summer, with the rhythm sections becoming fast friends between shows, kicking back and playing cards, while Jagger joined Tosh on stage for their duet ‘Don’t Look Back’. Meanwhile, whenever he was in Jamaica, Richards continued to drop in on his new found friends for off-the-cuff recordings for years to come, including ‘Shine Eye Girl’ by Black Uhuru, another musical partnership which would keep Sly & Robbie busy well into the 1980s. But it was a pairing with Island’s maverick label boss Chris Blackwell which would help define the next decade for the duo.

Blackwell had taken it upon himself to help reinvent model and singer Grace Jones who’d had moderate success with a trio of Tom Moulton-produced disco LPs. Inviting a disparate gang of musicians to his Compass Point studio in The Bahamas in 1980, Blackwell had the foresight to pair Sly & Robbie with former Blodwyn Pig guitarist Barry Reynolds and French-Beninese synth experimentalist Wally Badarou. The result was an otherworldly mix of slick lovers rock married with the wiry strains of post punk and new wave, with a dash of dubbed-out disco which would light up the sweaty dancefloors of New York City, championed by Larry Levan, Francois K. and Jellybean.

“Reggae’s expanding with Sly & Robbie” sang Tina Weymouth on the 1981 hit ‘Genius Of Love’ which Tom Tom Club recorded in the next room while the Compass Point All Stars were laying the foundations for Grace Jones’ Nightclubbing LP. In fact Sly & Robbie popped into the booth and added handclaps, giving their blessing to the quasi-hip hop mixup going down in studio B.

It was while working with the Compass Point crew that the duo approached Blackwell with their record label plans. Named after Sly’s choice of transport to their studio in Jamaica, the Taxi label had a slow start as the duo weren’t yet respected as producers, but with Blackwell’s blessing, recordings with Sly’s childhood friend Black Uhuru and the well respected Gregory Isaacs helped establish them beyond the session musician circuit.

As the 80s progressed, so did their experiments in sound, and everyone now wanted some of the magic they applied to the likes of Ini Kamoze, Dennis Brown and disco diva Gwen Guthrie. When producer John Collins was hired to helm the ‘Ghost Town’ recording sessions for The Specials, it was a copy of the Taxi-released ‘What A feeling’ by Gregory Isaacs which he used as a template for the sparse sound he wanted to capture, particularly Sly’s spare and spacious drums which was an antidote to Specials drummer John Bradbury’s often hectic and tom tom-heavy beatdowns. “I didn’t want him to have toms, or even a crash”, Collins told this site, “so I played him Sly Dunbar as an example.”

By the mid 80s, Sly & Robbie were now stars in their own right. The flourishing working relationship with Island led to a succession of their own albums from the dub-laced dancehall of Taxi Connection to the post-Slent Teng electro-funk of Rhythm Killers which featured ‘Boops (Here To Go)’, an afro-futurist sonic weapon which was later appropriated for the backing track of Suzanne Vega’s surprise crossover hit ‘Tom’s Diner’ in 1990 when British production outfit DNA spliced Sly & Robbie’s ragga meets go-go boogie with Vega’s a capella classic.

When Blackwell sold Island to Polygram in 1989, his experimental ethos would slowly trickle away from the label, but the upshot was a large injection of funds which helped steer various Taxi productions towards the top of the pop charts. Chaka Demus and Pliers had huge international hits in the early 90s with ‘Twist & Shout’ hitting number 1 in the UK. Dancehall heavyweights including Beenie Man, Capleton and Maxi Priest enlisted the duo, while Suggs hired them for his solo debut The Lone Ranger in 1995. Even Elton John and Tim Rice sought their production prowess for Sting’s ‘Another Pyramid’ in their 1999 rock opera Aida.

Into the 21st century, while they never seemed to stop working or looking forward, testament to the longevity of earlier material, Damien Marley had an international smash when his anthem ‘Welcome To Jamrock’ revisited a rhythm they’d originally produced for Ini Kamoze’s ‘World-a-Music’ back in 1984, and it got a second lease of life when Ashley Beadle then re-edited it for Island with the vocal from Bob Marley’s perennial ‘Get Up Stand Up’

They continued pushing boundaries and rocking dancefloors right up until the untimely death of Robbie in December 2021. Between the two of them, they notched up thousands of credits on everything from reggae to dub to electro to rock, even spending a brief moment in 1979 helping Serge Gainsbourg shift into a quasi-reggae phase, which delighted as many as it horrified. Still, today, it seems clear that the controversial French musician made a great foil for the music produced by the Jamaican rhythm section, exemplifying a sound which knew no boundaries. My only regret is we’ll never hear a Sly & Robbie dub-disco reimagining of ‘Strategy’ from KPop Demon Hunters.