It’s customary to view the musical career of Scott Walker, whose death was announced earlier today, as being made up of several distinct phases. One could argue for six of them. First of all, there were his early American years as a teenage singer of bubblegum pop and as an increasingly accomplished session musician. Then there was his time, in the UK now, as frontman of chart-topping mid-60s pop trio The Walker Brothers. Then the first phase of his solo career, producing the Scott 1-4 albums, followed by the “lost years” of MOR cover albums and the mid-70s Walker Brothers reunion. The last of these, Nite Flights, begins his supposedly reclusive period, broken only by the tentatively experimental Climate Of Hunter in 1984. And then finally there is Scott’s avant-garde renaissance heralded by 1995’s Tilt and followed by The Drift in 2006 and Bish Bosch in 2012, a loose trilogy of monumental works around which his other recent musical experiments orbit like strange erratic satellites.

I would argue however that these distinctions are largely illusory, and that there is a definite sense of continuity throughout Scott Walker’s entire body of work. The Walker Brothers emerged from the same early 60s world of manufactured pop product that Scott’s juvenilia- those early singles as Scotty Enge l – but they did it brilliantly, with just the right amount of originality and flair, while Scott continued to learn his craft and increasingly took control. His early solo albums were not initially dissimilar to his Walker Brother’s work, just more adult and sophisticated, and neither do his early 70s albums break entirely with the style he’d already established, though many, including Scott himself, would later see them as a retreat.

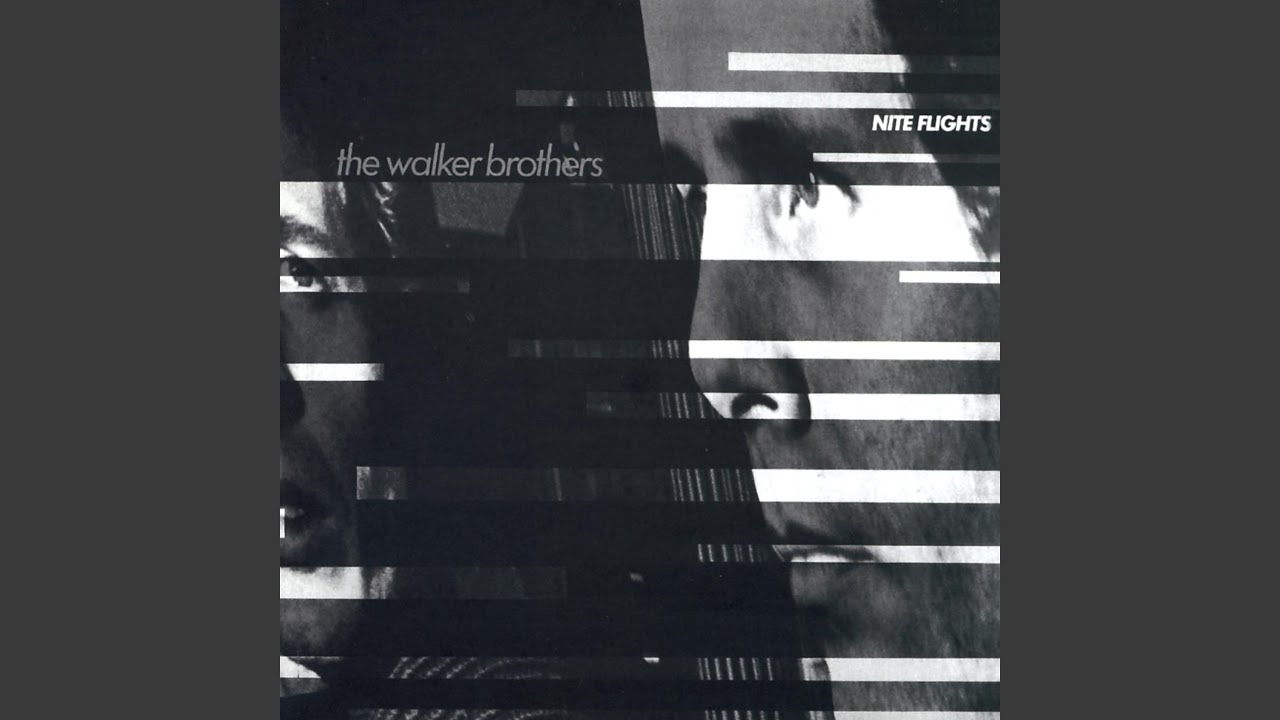

The Walker Brothers’ reunion albums No Regrets and Lines follow in the same vein, but emerging from this period is 1978’s Nite Flights, perhaps Scott’s most dramatic leap forward, albeit a tentative one as the album’s daring reputation rests largely on the four tracks Scott wrote himself. Nevertheless, these form the template for what was to come, and the development from Climate Of Hunter to Tilt and on to The Drift and Bish Bosch is clear, even down to the long periods of silence between each work – long gaps that make each successive album seem like more of a radical departure than it actually is, rather than another expression of the same artistic vision, just eleven or six years further on.

Pop or rock artists aren’t meant to make their greatest works 40-odd years into their careers, and some would say that to do this Scott Walker had to leave pop and rock behind him completely. But perhaps he just recognised how far the boundaries of what can be considered pop or rock had been pushed back during that period, to the extent that they are now largely permeable. Scott Walker made his first record in 1957, at the age of 13. Other singles released that year include Elvis Presley’s ‘Jailhouse Rock’, Jerry Lee Lewis’s ‘Great Balls Of Fire’ and Buddy Holly’s ‘Peggy Sue’. Paul McCartney and John Lennon first met that year, as schoolboys attending a village fete.

This is rock and pop’s antediluvian era, an unimaginable amount of time ago in terms of musical history. Scott’s commercial heyday and period of greatest fame lasted only a couple of years in the mid-60s, and for him to return in the 21st Century with incredible new music that is on the surface the complete antithesis of the style he was initially known for seems unthinkable. And yet, it happened. And what is more, it actually fits the story. It fits the image. It is exactly what “Scott Walker”, the fictional character created by Noel Scott Engel during those mad mid-60s years, would have ended up doing. It is the perfect conclusion to the myth cycle begun all those years ago, that spans the entire history of rock and pop music as we know it.

Scott Walker supposedly hated being a 60s pop star. He hated being a teen idol, being molested by screaming girls, playing gruelling package tours where no-one was interested in the music anyway, and having to constantly compromise with record company demands for quickly recorded commercial product. But for all his protests at the time – drinking too much, several suicide attempts, running off to become a monk – he also revelled in the role, not only playing the game but mastering it, becoming a conscious and creative participant in his own pop star iconography.

After all, as we’ve seen, Scott was a showbiz kid. He’d already spent several years trying to make it in the States, recording a half-dozen flop singles as an underage singer and playing some high-profile gigs as a session musician – that’s Scott laying down the bass on Sandy Nelson’s all-time classic beat instrumental, ‘Let There Be Drums’. He’d worked with Phil Spector’s right-hand man, Jack Nitzsche, and it was Scott who brought Spector’s Wall Of Sound orchestral production technique to those classic Walker Brothers’ tracks, with everything including the kitchen sink, in fact probably three kitchen sinks, all played live together in the studio. Of course credit must also go to the great producers and musical arrangers Scott worked alongside in those years, most notably Johnny Franz, Ivor Raymonde (father of the Cocteau Twins’ Simon Raymonde) and Reg Guest. Guest, who eventually retired to live in Hove, continued to work with Scott on his revered solo albums, alternating with Angela Morley, then known as Wally Stott.

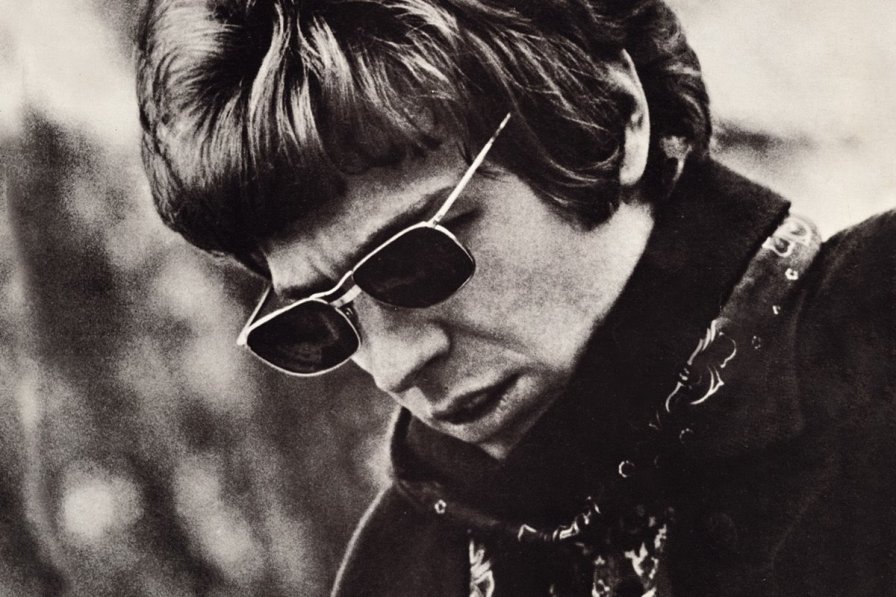

Three factors made the Walker Brothers great: the sweeping orchestral arrangements, the voice, and the image. Scott contributed to all three aspects. He actively cultivated a particular mystique, taking lessons from another American in Europe, PJ Proby and playing on the exoticism anyone from the US still had to a parochial British public. More than that though, Ohio-born Scott Engel indulged his love of European films, art and literature to create his idealised pop star in the fictional Scott Walker: like one of the Beatles re-imagined by Jean-Luc Goddard, or a male Greta Garbo as conceived by JD Salinger. He would turn down 20 interview requests only to accept the 21st; he would step into the spotlight fleetingly onstage, teasing his adolescent audience to breaking point and sometimes beyond before making his entrance.

The hair, the shades, the black clothes, the serious puppy dog stare and the significant hand gestures – shamelessly stolen by number one fan Jarvis Cocker – all contributed to the creation of “Scott Walker”, the reluctant pop star, the boy-child intellectual heartthrob, the existential sex symbol with a punkish disdain for stardom who would eventually go on to write avant-garde modernist symphonies. “Scott Walker” as played by Engel was just a more sophisticated variant on the classic boy band options – the moody one, Serious Spice, the dreamy interesting type who might not be the greatest dancer but who would gaze deep into your eyes and tell you how he read books and everything.

By this way of thinking, the Scott that made his first four solo albums – now critically revered as some of the greatest and most innovative albums of the 1960s – was just the same introspective pop boy grown up and aimed at an older audience. Walker found a new role model in the Belgian chansonnier and vicious satirist Jacques Brel, and translations of Brel’s songs by the Tin Pan Alley songwriter Mort Shuman formed the backbone of albums 1-3 in the Scott series, as well as providing the template for his own compositions on those records. For an English audience at least, Walker was more accessible than Brel, but he was also stranger. If his interpretations of Brel’s songs smoothed out some of their original spleen and righteous anger then they added an almost psychedelic sense of disassociation, a seductive darkness and a flirtation with madness and surrealism. This influence was also evident on Scott’s own Brel-inspired compositions like ‘The Amorous Humphrey Plugg’, ‘Big Louise’ and the incomparable ‘Plastic Palace People’.

Simultaneous with these dark, experimental outings however, Scott was also cementing his position in the world of light entertainment. Although a cool and with-it habitué of 60s London, Scott was never part of the underground. Unlike, say, the young David Bowie, you would never have found him at the UFO Club, hanging out with Pink Floyd or reading International Times. Scott’s closest showbiz friends were Jonathan King and Kenny Lynch, and between 1968 and 69 he hosted his own primetime variety TV show, while being a frequent guest on similar shows hosted by the likes of Dusty Springfield and Cilla Black. In 1969 he released the album Scott Sings Songs From His TV Series, a set of MOR standards that showed Scott more in thrall to Jack Jones or Matt Monroe than Brel or Stravinsky.

That same year the entirely self-penned Scott 4 – his most experimental album to date, now regarded as his masterpiece- was his first flop, and Scott immediately retreated to safer pastures, with a run of early 70s albums entirely made up of MOR ballads and country and western numbers, all covers, which were critically ignored and commercially negligible. In fact, these ‘lost years’ albums find Scott singing as strongly as ever, and while they are far from ground-breaking they feature creditable interpretations of songs by the likes of Randy Newman, Jimmy Webb and Burt Bacharach – hardly lightweights. Existing in a whisky-sozzled twilight easy listening world far removed from the progressive, glam and art-rock advances of the early 70s, they are nevertheless not out of character and repay renewed listening today.

Whatever the retrospective merits of these records however, there was a definite sense that Scott Walker was fading from view. A cash-motivated Walker Brothers reunion in 1975 saw the boys return to the charts with an irresistible take on Tom Rush’s ‘No Regrets’ before the law of diminishing returns set in, and Scott and his fictional siblings seemed destined for a future of cabaret shows and living from one 60s royalty cheque to the next.

But this was not the way that the mythical Scott Walker would go out. Scott Engel chose to make it heroic and to reboot his character for the post-punk era, betting everything on one final roll of the dice in a reunion that was on its last legs anyway. So Nite Flights was the only entirely self-penned Walker Brothers album, with Scott and John contributing four songs each and Gary making his only Walkers writing and singing contributions with the middle pair. Inevitably, it was Scott’s quartet that stood out, not so much like sore thumbs as like screaming hairless victims of electro-shock torture. Although John and Gary also show progression and innovation in their writing contributions, Nite Flights was both the last Walker Brothers album and the beginning of Scott’s modernist, experimental reinvention.

‘Shutout’, ‘Fat Mama Kick’, ‘Nite Flights’ and ‘The Electrician’ may have been startling, but they also picked up where that Scott Walker left off, on Scott 4 nearly a decade earlier, albeit retooled for a sparser, synthesised age. It didn’t hurt that Scott was one of the few 60s pop stars still considered acceptable by a new musical generation who had embraced the Sex Pistols’ ‘Year Zero’ scorched earth policy. The new pop was emerging, but it still needed role models, and in rejecting ‘rock’ for the bloated behemoth it had become by the mid-70s, singers like Ian Curtis, Marc Almond, Ian McCulloch and Julian Cope were closer to crooners than blues belters, and Scott Walker was a much hipper and more viable figure to imitate than Bing Crosby or Perry Como. Julian Cope in particular was such a Scott evangelist he complied the album from which this night takes its name, releasing it in 1981 on Bill Drummond and Dave Balfe’s Zoo label in a blank, matt grey sleeve expressly intended to appeal to the long-overcoated post-punk brigade who bought Teardrop Explodes and Joy Division records, but would be turned off by anything suggesting corny 60s schmaltz.

Another singer who’d been watching Walker closely for years was David Bowie. The Thin White Duke surely came to Jacques Brel via Walker’s interpretations, and like Walker created his own Brel-like persona and songs, in his case adding a glam sci-fi element to create The Rise And Fall Of Ziggy Stardust And The Spiders From Mars. Bowie’s mid-70s collaborations with Brian Eno, Low and Heroes, surely had a profound influence on Nite Flights, and Nite Flights can in turn be seen as an influence on Bowie and Eno’s next record, 1979’s Lodger. Bowie would go on to cover the title track on 1993’s Black Tie White Noise, an album that saw him also returning to more experimental work after several years of playing it safe with relatively bland, commercial material.

Yet while Bowie embraced mainstream stadium pop and its attendant financial rewards in the 80s, Scott Walker all but vanished from view. The Walker Brothers’ reunion collapsed as expected, and Scott was silent until 1984’s Climate Of Hunter, a perplexing album that was neither fish nor fowl: a definite continuation of the mood and sound of Nite Flights, and with hindsight a foreshadowing of what was to come on Tilt, but ultimately an odd mix of experimentalism and polished 80s rock that saw Mark Knopfler and Billy Ocean contributing alongside free jazz saxophonist Evan Parker.

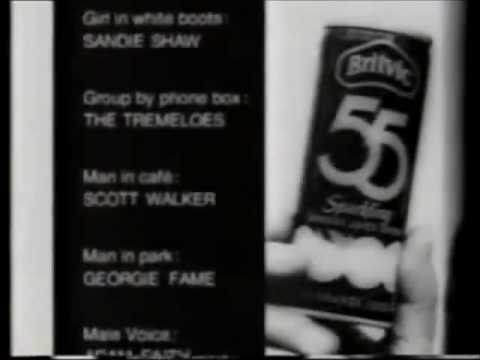

It could have been a lot worse. The 80s were not kind to once-credible stars of Scott’s vintage, even if some cashed in their reputation in order to shore up their bank balance. Climate aside, Scott once again took the mythical route. He did nothing. He did so much nothing, so loudly, that he began to be spoken off as a recluse, which was perfect. Of course that Scott Walker, the be-shaded 60s existentialist, should spend the 1980s in a darkened room with the curtains drawn, listening quietly to impenetrable modern jazz while a succession of Moroccan houseboys slipped wafer-thin mints under his door, or something like that. In 1987 he briefly appeared, alongside Sandie Shaw and other near-forgotten but fondly-remembered 60s stars, in a Britvic TV ad. It should’ve been naff; actually it was genius, the equivalent of teasingly placing one twirling hand into the spotlight then withdrawing it, as he would do during mid-60s Walker Brothers live shows. It was just enough of an appearance to keep people wondering. It all fed the legend.

And then the 90s happened, and the 60s became cool again. Actually the past became cool again. CD reissues and the rise of magazines like Mojo meant that pop’s history was being rewritten and re-evaluated, and pre-punk acts previously excommunicated by the Stalinist music press of the 1980s were now fondly rehabilitated by the new regime and even allowed to make tasteful, critically acclaimed comeback records. It’s fair to say however that no-one else made a comeback record quite like 1995’s Tilt.

At the time, Tilt seemed difficult, obtuse, wilfully avant-garde and even pretentious. Now it sounds incredibly listenable and, though still bold and brilliant, surprisingly accessible. It’s hard to recall the degree to which it seemed to come out of nowhere, a self-willed dream soundscape drawing on half-remembered Pasolini films, modern classical minimalism, lieder, the early stirrings of post-rock and traces of industrial music. It was, of course, exactly the kind of record the mythical Scott would produce on emerging from self-perpetuated exile, and remains a brilliantly executed work of genius.

Yet many were deeply unsettled by Tilt, having hoped for the return of the 1960s balladeer, not realising that sun definitely wasn’t going to shine anymore. One wonders if those people had even heard Climate Of Hunter or the first four songs on Nite Flights. Nevertheless, Tilt continues to be seen as drawing a line between the old, nice Scott who had a lovely voice and a way with a tune, and this new, defiantly unapproachable Scott, singing fragments of diffuse melody in a voice higher than his natural range over a backing of impenetrable scrapings and clanks. It also won Walker many new fans that had little interest in his older work.

Scott too, while still somewhat playing the recluse card, gave selected interviews in which he was dismissive of his earlier work and his years as a manufactured pop star. But in truth, there was no line in the sand, merely a sometimes buried, sometimes visible thread connecting six separate myth cycles in the development of the godlike genius of Scott Walker: a genius that Noel Scott Engel had gradually willed into being across the entire history of rock and pop.

Another eleven years passed, before The Drift saw Scott Walker revealed as a fully-fledged modernist composer utilising elements of both post-rock and the classical avant-garde, as well as being a writer of fractured surrealist poetry that corralled the confusion and horror of the entire 20th century into its remit. Although it didn’t elicit the same sense of shock as its predecessor, The Drift was in fact as much a step forward from Tilt as that record was from Climate Of Hunter, and unlike Tilt, after another eleven years it remains a forbidding and challenging listen. 2012’s Bish Bosch was very much The Drift part two, and was every bit its equal. Adventurous soundtrack work and a collaboration with art-doom-metal trio Sunn O))) would follow, but in truth there seemed little more to add.

I loved Scott Walker in all his phases. I loved that the same artist performed ‘The Sun Ain’t Gonna Shine Anymore’ and ‘SDSS1416+13B (Zercon, A Flagpole Sitter)’. I loved that between those two poles he also gave us ‘Montague Terrace In Blue’ and ‘The Old Man’s Back Again’ and ‘No Regrets’ and ‘The Electrician’ and ‘Farmer In The City’ and so on. Not only are these all incredibly songs brilliantly performed, but throughout it all there was the ongoing performance of Scott Walker, gradually revealing to us the many facets of his character. From moody teen heartthrob to the darling of the avant-garde, Scott Walker represented the full potential of pop music for emotion, expression and innovation. The presence of artifice should not detract from the creation of a true myth figure who could not be more aptly named: Scott the Walker, striding always ahead, a colossus forever vanishing over the next horizon. His loss is a great one.