Patrice Chéreau died on Monday 7th October 2013. He leaves behind no legally recognised partners or biological heirs, and a body of work marked by its stringent sexlessness, to be assessed on its artistic merits alone. Besides his film and theatre work, he is widely recognised as having changed the staging of opera forever.

I was 17-years-old in 1998 when I saw Patrice Chéreau’s Those Who Love Me Will Take The Train. I had the most burgeoning and shy of sexualities and a mind only just beginning to seek out new ideas and experiences away from the influence of family and friends. What I saw in this film – the lyricism of Chéreau’s meditation on love, life and death – moved me probably beyond anything I had seen in the cinema at that point. I found myself responding in un-intellectual ways to the film, ways that I couldn’t have predicted and wasn’t able to make sense of; it spoke to me physically, I had a kind of keening urge towards it, something surging in me towards the pictures and sounds. Does that sound dramatic? It’s only an attempt to explain what it’s like to recognise yourself, things you have thought and felt, in a work of art – the way, unbeknownst to you before the lights went down, you yourself would be spoken to directly by the film. Woody Allen did this in The Purple Rose Of Cairo, when Jeff Daniels’ film star spoke directly to Mia Farrow’s dejected housewife in the audience, right there from the screen. The familiarity of a work of art that speaks to you can be in some extreme cases an act of liberation, of rescue even.

Those Who Love Me Will Take The Train tells the story of friends, lovers and family of an artist who has recently died, who all take a train from Paris to attend his funeral together. En route, of course, passions fuse and old stories are dredged up, which is as things should be. Chéreau’s skill in the film is to keep a tight rein on his characters, while allowing their personalities to be drawn out, to be thrown into relief, by the events. In his directing he is a realist, but with a weird kind of lyricism that lies somehow behind the actions you see on screen – calling to mind Larkin’s line about spring, “like something being almost said". Most of all, for me, in 1998, the film snapped and fizzed because of the way it talked about outsiders (Vincent Perez’s performance as a transgender woman, played with dignity, was eye-opening) and for its vibrant, aching sexuality. The love triangle between three men in the film – the understanding intimated in small looks between two characters, the unbearable tension caused by physical proximity, the hot and awkward fumblings at various seized moments; all of this drove me almost wild with a sense of at last belonging. Chéreau’s genius in the film was to offer up love and sex as travelling partners with death – the spectre of AIDS still very much in everybody’s thoughts – and to represent in an artistic mode, alongside conventional social rituals, a narrative that was very much at a remove from public consciousness. It is a heart-rendingly beautiful film, made with sensitivity and skill.

When Chéreau died last week, I felt a kind of tug inside of me again. But when I scoured the obituaries in French newspapers for some sort of reflection on the way his homosexuality influenced his best work, I was stunned and disappointed to find no acknowledgement of his sexuality. I don’t know what the conventions of obituary writing are – what choices obituary writers have to make in acknowledging or making known various elements of a dead person’s life – but there remains something essentially problematic here in avoiding the topic of an artist’s orientation. In a profile of him on radio station Europe 1, ‘G.S.’ mentions his sexuality and his comment to Télérama that he didn’t think his homosexuality should authorise him only to talk about gay things, and quotes him as saying that he believed the line between heterosexuality and homosexuality was very fine and fluid. Fair enough. Those Who Love Me… in particular deals with all sorts of love relations, and in La Reine Margot and Intimacy he did a fine job of talking about straight sexual passion.

But Chéreau did more than that, and his homosexuality – his queerness – runs through his work like letters in a stick of rock. It isn’t calumny to point out that his perspective is consistently a gay one – in Intimacy for instance, with its sharp-eyed, somewhat melancholy view of sexual hook-ups and its poignant depiction of two people lying to their partners and themselves. The characters are played by Mark Rylance and Kerry Fox, but Chéreau’s eye, his camera, his modulation of the story, his depiction of sex, are all heavily indebted, at least as far as I can see, to his own sexuality. I haven’t seen Chéreau’s work in theatre and opera, but I know at least that he is credited with revolutionising the mise en scène of opera by subjecting it to the same rules of dramatic reinterpretation as we now accept as the norm in straight theatre. In other words, Chéreau put his own spin on the classics, giving them a personal or political inflection: I don’t think it’s banging too much on the homosexuality drum to suggest that someone growing up gay in the 50s and early 60s, directing theatre and opera and feeling at a distance from mainstream artistic production, might be enacting one of the primary gay methods of expression, which is to put a queer spin on a more conventional narrative or trope. Is that going too far?

Homosexuality is present not merely in Chéreau’s outlook – although as I argue, his stance is essentially gay and he often returns to a gay ‘canon’ in his work – but is there in the actual stories he chose to tell. The film that made Chéreau’s name, and which he himself used to call his true first film (meaning, I think, his most personal film at that point) is The Wounded Man. Centring on Henri (Jean-Hugues Anglade), an adolescent who falls for an older man, Jean, at a train station, the film is an investigation, before the AIDS crisis reached its height, of the murkier aspects of homosexuality. To win Jean’s love, Henri starts prostituting himself: in addressing the sexual act as a transaction, Chéreau was treading the same sort of ground as the play he would keep returning to throughout his career, Bernard-Marie Koltès’ In The Loneliness Of The Cotton Fields – a play greatly influenced by Jean Genet. Koltès, a close collaborator of Chéreau’s, was an advisor on The Wounded Man and openly gay; he died in 1989 of complications due to AIDS.

Chéreau’s co-writer on The Wounded Man, Hervé Guibert, was a lover of Michel Foucault and would also go on to die of complications arising from AIDS, in 1992. He and Chéreau wrote a film that harked back to Jean Genet’s idea of a gay underworld. It depicted homosexual relations as equally sordid and exciting, portraying a group of people on the margins of society. Chéreau denied at the time that he had made a film about homosexuality, claiming that it was about any sort of youthful passion – and it may be understandable that in 1983 he was uneasy about being categorised as a purely gay artist. But it really is an early and brave example of a ‘gay’ cinema, anticipating New Queer Cinema by nigh on a decade.

Those Who Love Me… would return to explicitly gay themes in 1998, and in 2003 he directed His Brother, a film offering a more serene view of homosexuality, about two brothers, one gay and the other not, and their difficult relationship. It is a lovely film, and one that feels like the work of a man who has worked through a number of concerns and achieved something like reconciliation with himself.

During Chéreau’s director of the Amandiers theatre in the 1980s he met the actor Pascal Greggory, who would become his partner. Le Monde describes Greggory in its obituary as "one of his actors of choice" and Libération as "one of his recurring actors". L’Express refers to Greggory as ‘his “muse”’ (inverted commas theirs). I am personally tired of scanning obituaries for a proper acknowledgement of gay people’s partners: in the Guardian’s obituary of Maurice Sendak last year, it was oddly stated that “he never married” (indeed, since gay marriage never existed in the USA in his lifetime) and that his dog was the love of his life, only for a hurried acknowledgement of the actual love of Sendak’s life (Robert Glynn, his partner of 50 years) to be smuggled into the last paragraph of the article. The New York Times’ obituary of John Cage in 1992 famously skirted around the issue of his sexuality, noting almost in passing his collaboration with Merce Cunningham and the fact that the two men had travelled to Europe together: these tidbits, as in Victorian days, being little scraps of innuendo thrown to discerning gay readers who might be happy to catch the allusion, without tarnishing the great man’s reputation by declaring it outright. The New York Times rectified things somewhat when Cunningham himself died, in 2009, with a central paragraph making clear that Cunningham’s best work was made with Cage, who is cited as Cunningham’s “collaborator and companion.” This is only right.

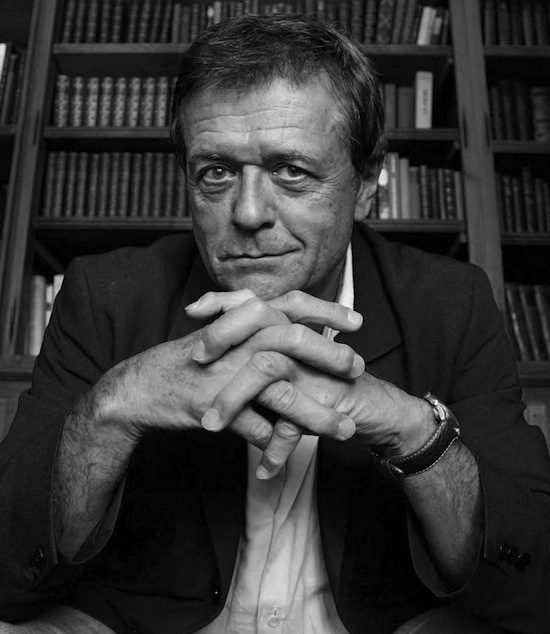

Chéreau lived with Greggory for a long time, and I am astonished not to see this stated in articles: however long the relationship may have lasted, the bond between the lovers clearly influenced Chéreau’s work over a number of years. The pair met in 1989, and would continue working together at least until 2005’s Gabrielle. In all of their collaborations, Greggory’s combination of rugged good looks and oddly sensual vulnerability shines through. Greggory is angular, other-worldly: he is both intellectual in his poise and intensely physical. Chéreau filmed him in main roles three times, and worked with him several times more in the theatre, first directing him in The Loneliness Of Cotton Fields and then playing opposite him in another production of the show. In Gabrielle, Greggory offers an interesting take on masculinity, playing a despised husband to Isabelle Huppert’s title character: he seems to act almost as Chéreau’s accomplice in a kind of meta-fight with Huppert, reflecting on-set tensions that are clearly felt in the film. You sense the closeness of the two in all their work together: it is present in the form of an understanding between them, where Greggory exists as a desired object and an incarnation of Chéreau’s mind.

Undeniably, Chéreau rejected his sexuality as a tag, and was loath to recognise that his work was in itself gay. Certainly, he told stories that had cast a far wider net, in the cinema as well as in theatre and opera. But in equal measure, his work bears the hallmarks of his sexuality, and is inflected with his own idiom that owes much to a homosexual outlook and cultural lineage. I think that a degree of inhibition existed, too, in Chéreau’s generation, in accepting that telling homosexual stories was not in itself pejorative or implying a lack of quality or universality. These are not things that, in my estimation, need concern the writer of obituaries. Gay people, as Harvey Milk had it, need to be out and represented properly in the media. We have to reclaim work that is part of our collective history, and we can be proud to claim the work of artists like Chéreau as our legacy.