Like Spike Milligan, Ozzy Osbourne told us he was ill. “I’m going to make this fucking gig if it’s the last thing I do. Well, it will be,” he told SiriusXM a couple of months before he played his farewell concert, Back To The Beginning, at Birmingham’s Villa Park on 5 July.

Fortunately, he did a decent job on the day, with Quietus writer Keith Kahn-Harris taking careful notes about his physical condition in this amazing report and concluding, correctly, that the singer still had what it took. It was all the more shocking, then, that Ozzy succumbed to undisclosed causes on 22 July.

Still, there’s a certain elegance in the fact that Ozzy played his biggest gig in decades just before his death. A broader and equally poetic theme of his story is that he, and his band Black Sabbath in parallel, pulled off an enormous coup by coming out of poverty and profiting against the odds within a hugely overpowered music industry, the obvious caveat being that they were endlessly ripped off and almost lost their minds along the way.

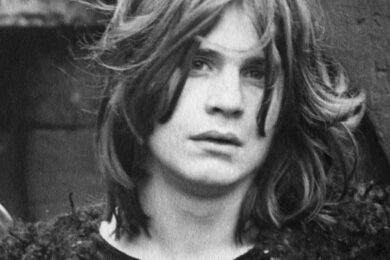

The modern entertainment business is largely (and increasingly) populated by people who possess social, cultural and financial capital and who enjoy a certain degree of privilege. Ozzy was the opposite of that kind of person. He was born John Michael Osbourne on 3 December 1948, and raised in the home of his parents Jack and Lillian at 14 Lodge Road in Aston, a bombed-out suburb of Birmingham. By rights he should have spent 45 years working in a factory before dying in his 60s, that being the traditional career path for men of his era and demographic. Instead, he became one of the world’s most recognisable rock stars. What were the chances?

‘Low’ is the answer. Aston was a pretty grim place back then, having taken a beating in the Second World War only four years previously, and most of the local population lived in impoverished conditions. Violence was widespread and homelessness was common, although Ozzy and the three future members of Black Sabbath – Tony Iommi, Geezer Butler and Bill Ward – also seem to have felt that Aston possessed its own form of beauty, according to their autobiographies.

Ozzy, who attended King Edward VI Grammar School on Aston’s Frederick Road, once described his schoolroom persona as “the original clown”, although there was a darker side to his personality. He attempted to hang himself at the age of 14, although his father caught him in the act, rescued his son and then beat him. Presumably that made a kind of sense.

The future star’s school education included some pretty eye-opening incidents. He apparently attacked one of his teachers with an iron bar and got into occasional scrapes with Iommi, a tough individual with the brawn to back up his temper. Still, Ozzy found some solace as a performer in productions of HMS Pinafore, The Mikado and The Pirates Of Penzance, before quitting school at the age of 15.

The adult world of work was hardly welcoming: Ozzy’s first job was as a tool-maker’s apprentice, where he cut the end of his thumb off on the very first day. He then moved through a succession of more or less desperate jobs, including killing livestock in an abattoir. He hit bottom in a car-horn factory, where he felt his sanity slowly giving way.

In 1965 Ozzy attempted to join the army in an attempt to escape the factories. “I was 17 and pissed off,” he told the writer Sylvie Simmons. “I wanted to see the world and shoot as many people as possible… How far did I get? About three feet across the fucking front door. They just told me to fuck off. He said, ‘We want subjects, not objects’. I had long hair, a water-tap on a string around my neck for jewellery, I was wearing a pyjama shirt for a jacket, my arse was hanging out and I hadn’t had a bath for months.”

A stint in prison came in 1966 for breaking and entering, which Ozzy had messed up gloriously. He was an incompetent burglar at best, once wearing fingerless gloves while attempting to steal goods from a local clothes store. He was offered the alternative of a £25 fine, but instead served six weeks of a three-month term in Birmingham’s Winson Green Prison. A second sentence there followed when Ozzy chose, in his infinite wisdom, to punch a policeman in the face: while inside, he alleviated the boredom by tattooing O-Z-Z-Y across his left knuckles with a sewing needle.

Inspired by the Beatles, Ozzy decided in the absence of any other options to become a singer, passing through unremarkable bands such as the Prospectors and Approach before placing an ad on a musicians’ noticeboard which read: “Ozzy Zig requires gig. Owns own PA”. The ad was read with interest by one Geezer Butler, who recruited him to his band Rare Breed, which later merged with Ward and Iommi’s groups to become Earth and finally Black Sabbath, after the 1963 horror film.

From the very beginning of Sabbath’s career, the industry attempted to exploit the four naive Aston kids. One example of this came when an early manager, Patrick Meehan, arranged for them to play the California Jam festival in 1974, a gig for which the band were paid $250,000 ($1.6m today), all of which he pocketed apart from a $1000 fee per musician. By 1973 they were being defrauded on all sides. “Around the time of [fifth album] Sabbath Bloody Sabbath, we’d found out that we were being ripped off by our management and our record company. So, much of the time, when we weren’t onstage or in the studio, we were in lawyers’ offices trying to get out of all our contracts,” Butler told Guitar World in 2001.

The Sabbath members’ lack of education and status made them vulnerable to exploitation, like thousands of hapless acts before and since, and even when they weren’t being relieved of their rightful earnings, they were treated with derision. Frank Zappa referred to their music as “the worst kind of heavy metal sickness”; Rolling Stone labelled it “bubblegum Satanism”; Roger Waters of Pink Floyd dismissed it as dull in a Melody Maker interview. Sabbath’s working-class roots, combined with the relatively unsophisticated nature of their early music, just didn’t please the critical ears of the establishment.

Still, Sabbath’s first few albums weren’t diminished by any of this. Their most influential songs – ‘Paranoid’, ‘War Pigs’, ‘Iron Man’ and others – redefined heavy music and inspired a vast number of musicians to pick up instruments.

The lifestyle wasn’t good for Ozzy, but he had resilience to spare, it turned out. When Sabbath fired him, then an intoxicated wreck, in 1979, his future wife Sharon Arden rescued him and set him on a solo career which, against all expectations, swiftly outperformed his old band. His albums, of which he eventually recorded thirteen, leaned in more of a radio-friendly hard rock direction than the riff-heavy gloom of Sabbath, attracting a huge audience on both sides of the Atlantic.

Over the next four decades, Black Sabbath reunions came and went, wars of words were exchanged, legal battles raged, and eventually bygones became bygones. The Back To The Beginning show was Sabbath’s literal last act.

Even a highly compressed list of Ozzy’s lifetime achievements is impressive. Most of Black Sabbath’s 70 million albums sales came from LPs on which he featured; they won three Grammys; they were inducted into the Rock And Roll Hall Of Fame; and they invented heavy metal. (Yes, they did.) As a solo artist, Ozzy sold a similar number of albums (accounts vary), winning five Grammys, also entering the RRHOF and being inducted into many, many similar rolls of honour. Sharon Osbourne’s Ozzfest redefined the rock festival concept in the late 1990s, and the 2002 MTV series The Osbournes was among the very first big-selling reality-TV series, for better or worse.

The marketing was always clever, too. Ozzy was branded ‘the Prince of Darkness’ for no obvious reason other than it sold records and got people talking, but it worked. He was an alcoholic and drug abuser who stumbled from mishap to mishap – biting the heads off a dove and a bat in 1981 and 1982; the Alamo incident in Texas and the tragic death of his guitarist Randy Rhoads, both in 1982; the attempted murder of his wife in 1989; the quad-bike accident in 2004 that nearly killed him; a petty feud with Iron Maiden in 2005; a third-act affair with a hairdresser in 2016 – all of which were publicised, discussed and made essential parts of the saga.

Here’s the thing. All of this, good and bad, was Ozzy’s own work, and that of his wife and manager. Sharon brought industry connections to the partnership, sure, but at the same time she fought for Ozzy’s success: it wasn’t handed to him. How could it be, given his origins?

Ozzy has died, but he won’t stop being in the conversation. Like Lemmy before him, he will swiftly become a series of metaphors, both meaningful (his astonishing trajectory) and trivial (his reduction to clown status for the amusement of MTV viewers). It’s the former we should focus on in the Ozzy-less years to come. He rose to an impossible height from straitened circumstances and managed, more or less, to retain his humanity, despite the corrupt, amoral industry in which he worked. I met him and liked him: he was still who he appeared to be.

In the end, his success represents a triumph of the unprivileged over the wealth and power of the industrial-entertainment complex. It is almost impossible to do that nowadays: Ozzy will be one of the last examples of People 1, Business 0. Remember him for that.