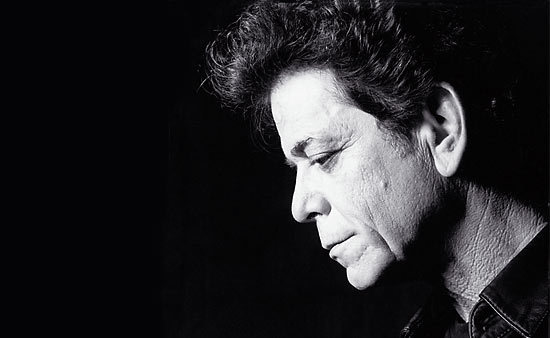

Lou Reed saw himself as the bard of New York; the way, he explained, Joyce had Dublin and Faulkner the South, though a sensibility awash in Poe, Delmore Schwartz and Nelson Algren will produce adolescent renderings of perversion. But he didn’t stop there. Reed’s fictive power acted as a window through which sympathetic parents, heterosexual marriages, and other tenets of the bourgeoisie look as deeply strange as kissing a boot of shiny, shiny leather. If rock critics remain as obsessed with lyrics as they ever were, Reed deserves the blame as much as Dylan. A pity. What’s astonishing about those Velvet Underground records is the success with which their musical correlatives complement if not overwhelm the lyrics. ‘Venus in Furs’, the ode to sadomasochism from the band’s first album, is sexy and thrilling and wondrous in ways that have little to do with the ooh-scary libretto. Listen as those Byrds-y guitars slam against the single note that John Cale saws off his viola, while Maureen ‘Moe’ Tucker bangs a kick drum; when Cale actually plays chords on the bridge the song sounds as tired and weary as Reed himself.

Reed understood form as requiring the redressing influence of content. The aqueous licks he and Sterling Morrison trade on ‘Some Kinda Love’ understand sexual fluidity as humankind’s truest natural state – a more accurate ‘statement’ than the sailor orgy in ‘Sister Ray’, which at least sounds like a sailor’s orgy, thanks to the caterwaul of Cale’s organ and Reed’s guitar. "Let us do what you fear most," he sang in ‘Some Kinda Love’ in the nasal voice of an older brother still afraid of his worst fears; Reed’s gift was to tremble for an audience ready to record those trembles as tremors. He loved music. There’s Motown chords in ‘There She Goes Again’, gospel undertones in ‘I’m Set Free’ (replace the guitars with an organ), hymnal qualities in ‘Pale Blue Eyes’. You could just dance to the rock & roll station, and it was alright. It was okay to feel – to sound – confused. Ellen Willis was right: "I guess that I just don’t know" was the best line this songwriter with literary pretensions wrote.

The Velvet Underground – ‘Some Kinda Love’For kids accepting their sexuality while their bodies contort and swell into unrecognisable shapes, Reed’s music made you feel alright. ‘All Tomorrow’s Parties’ suggested those kids could stitch an identity from hand-me-downs -like stitching a song from twelve-string, boogie piano, and Nico – to prepare a face for the faces they will meet. Often in the 1970s the face he prepared was just a prepared face. Except for the indelible trio of ‘Walk On The Wild Side’, ‘Satellite of Love’, and ‘Perfect Day’, the glam-slam gay tropes of 1972’s Transformer sound hollower than Bowie’s own thefts, and Reed had probably thought about kissing more boys than Bowie. The congealed fatalism of the following year’s Berlin illustrated the difference between sentimentality and cynicism, which is none, especially with Bob Ezrin arranging strings like Stanley Kramer directing It’s A Mad, Mad, Mad, Mad World.

The punk movement for which the press had called him hero coincided with an inward turn; as his followers got their teenage kicks he dropped the surly act and affected a ruminative singer-songwriter pose. The five-note cello hook and appropriation of ‘Waltzing Matilda’ in 1978’s ‘Street Hassle’ buttressed a high, uncertain Reed performance about a confused boy in love with a transsexual street walker. 1979’s The Bells boasted ‘Families’, a honking appraisal of how awful it must have been to grow up with parents like Lou Reed’s who had to deal with a kid like Lou Reed. The face in the mirror never stopped scaring him. The price he paid for growing up in public.

Robert Christgau once said that Reed’s throwaways matter more than his grand statements. Forcing audiences to regard transvestitism and ODs as normal has less resonance than showing, through his often terrible vocals and slapdash arrangements, how the quotidian and the banal are creepy. From ‘Vicious’ to ‘Sally Can’t Dance’ to ‘I Love You, Suzanne’ and ‘Hookywooky’, these songs apprehend life as something approached piecemeal, with a tentative smile, ready for new sensations that will – just you wait – curdle into old familiar ones. What a thrill to be part of the generation that adores 1975’s Coney Island Baby, the closest thing to a James Taylor album that Reed recorded: ten modest gestures, winners every one, peaking with a title song in which he confessed a suppressed desire to play football for the coach while soft-focus guitars chimed and hummed.

Syndrums, MIDI, and other 80s innovations confused many boomer rockers, Reed included, but only once – the defiantly ephemeral Mistrial. He spent the rest of the decade recording astonishing album after album in which he refined the essence of the four-piece rock band; he worked on it, like the marriage he celebrated and mourned. They’re not much liked by the fans who prefer the Dada gestures of his early 70s work, but, again, the subversions are subtler. The first of these, 1982’s The Blue Mask, played mirror games again: its cover is Transformer‘s but painted blue, as if to suggest a decade’s worth of concerns require merely a different mask. With Robert Quine he found his best guitar partner after Sterling Morrison. The opening of ‘My House’ unfolds like an orchestra fanfare, with Reed and Quine easing into the song, and bassist Fernando Saunders poking and digging a foundation. The man who in 1972 said he’d come out of the closet and onto the street now muttered about how women were great and a solace to the world; Quine’s terse, worried clusters of notes mocked Reed’s boasting. On the title track Quine, in a characteristic show of modesty, lets Reed play his most unhinged solo since ‘I Heard Her Call My Name’.

Its brutality – "Tear the blue mask off my face and look me in the eye" – a reminder that relationships must by necessity assimilate each partner’s quiet horrors, ‘The Blue Mask’ presaged 1983’s Legendary Hearts, on which Reed’s mixing down of Quine’s parts cost him critical support but in retrospect proved a shrewd aesthetic choice: the epithalamion turned into elegy. The songs are slower, sadder, sharper. 1984’s New Sensations attempted a pop crossover, Reed’s first since 1974’s Sally Can’t Dance. Infatuated with the sound of 80s drums, he mixed them really loud and ended up with a K-Mart approximation. No matter. The apex of Reed’s my-throwaways-are-diamonds ethos, New Sensations offers songs about watching a Sam Shepard play and male friendship, offers admissions of jealousy, offers MTV a shiny pop song. Reed, handling all guitar parts, masters the two-chord strum, the power solo, the fill. The Best Supporting Actor award goes to Saunders, who risks Pino Palladinoiserie with his high-end melodic parts, as eloquent as any by New Order’s Peter Hook.

Reinvigorated, Reed returned to the dubious satisfaction of concept albums, guaranteeing year-end placement and unconsulted and ignored reference book status in fans’ musical libraries. But listeners who get off on Mean Lou should reinvestigate 1989’s New York, in which our hero gets himself into a lather over Bernie Goetz, Jesse Jackson, and poverty while ignoring how Mike Rathke isn’t Robert Quine, or even Lou Reed. It still worked: ‘Dirty Blvd’ got him college radio play. 1992’s Magic & Loss, dedicated to Doc Pomus, is starker and duller – a series of freshmen themes set to (spare) music. But the Velvets revival that had started in 1985 validated Reed’s efforts. At last he was an Important Rock Artist, and if Pete Townshend could record prolix song poems, well, by God, so can Lou. For an encore he made up with the other Velvets for a pointless tour and live document, like any fortysomething rock & roller would.

Which explains why 1996’s Set The Twilight Reeling was a welcome surprise. Another valentine, this time to Laurie Anderson, which reconnected him to Manhattan, the city with which he had the deepest relationship of his life. More songs about stuff: egg creams, walking down Canal Street with your beloved, fat Rush Limbaugh, disgusting Bob Dole, the last two explored ‘Sex With Your Parents (Motherfucker)’ in which Reed plays guitar to match the title. His work on the title track – he excelled at title tracks – cries out for rediscovery. 2000’s Ecstasy was just as ruthless, thanks to Hal Willner’s muscular production. He recorded a seventeen-minute drone called ‘Like A Possum’ as if to prove he could, and then – here’s the trick – continued trolling fans for the rest of the decade. The Raven is another reference library record. As for the notorious LULU, of course it’s terrible, but that’s beside the point. That Reed still cared enough to risk mockery proved that a mainer in his vein still led to a center in his head.

To listen to Lou Reed in 2013 before his death meant reconnecting with one’s youth – a thought as repulsive to him as it would’ve been to John Lennon. His gift was to pretend each scab he scratched at was the first he’d ever seen. He set himself free, ready to find another illusion – can you think of a more adult feeling in rock music? So is looking to join the absurd with the vulgar. "I want the principles of a timeless muse," he insisted over chiming guitars in ‘New Sensations’, not giving a shit whether he was timeless or articulating principles. He recorded rock & roll. The rest is our problem.

The Velvet Underground – ‘Rock & Roll’