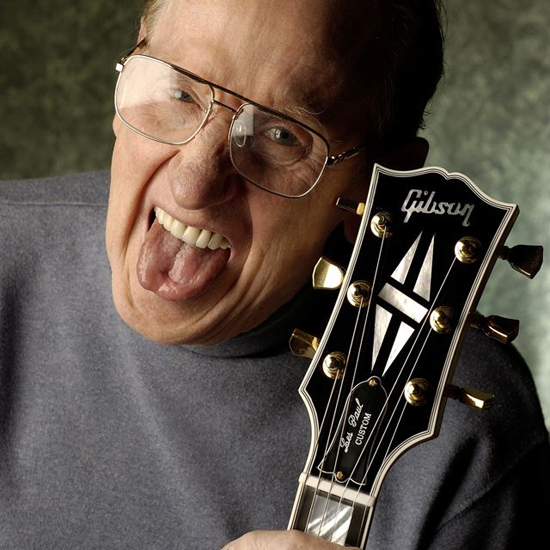

Les Paul: 1915-2009

========================

It’s a curious quirk of history that the guitar that has borne Les Paul’s name since 1952 is the creation he is most famous for. Because amongst this visionary’s many innovations, the Gibson Les Paul guitar is both the least radical and the one in which he had the least direct involvement.

The reality of Les Paul’s impact on 20th century music is that he more or less single-handedly created the very notion of the studio production, as distinct from simply recording a live performance, creating multi-track effects-drenched sonic oddities as far back as 1948.

Early life and career

Paul’s innovations in music technology bear one of the great hallmarks of genius; like Shakespeare’s invented words, they have become so ubiquitous as to appear almost obvious.

Born Lester William Polsfuss in Wisconsin in 1915, Les was something of a prodigy, playing guitar, harmonica and banjo by the age of eight. And as early as the age of ten, he came up with the neck-worn harmonica holder that enables guitarists to play gob iron solos while keeping their hands free. One way of looking at this of course, is that we have Paul to blame for Bob Dylan’s wretched parping, but we’ll let that slide.

Paul was first and foremost a performer, and this born-of-necessity inventiveness was at the core of all of his innovations.

"Honestly, I never strove to be an Edison," he told The New York Times in a 1991 interview. "The only reason I invented these things was because I didn’t have them and neither did anyone else. I had no choice, really."

By 13, Paul was performing semi-professionally as a country singer and guitarist, using a crude PA system fashioned out of whatever he found lying around. He had no formal training in electronics, but as he put it: "The electronics were all in my living room. In addition to the phonograph I had a player piano, a telephone and a radio. I took the telephone apart at the receiver end… and quickly understood what the receiver was doing. Then I looked at the mouthpiece and worked out what that was doing. It was all right there in the living room."

By his late teens, he was a fully professional guitarist, largely in radio studio bands. Cleverly exploiting the invisibility of the radio performer, he ran a number of alter egos in parallel throughout the thirties, including "Rhubarb Red", a hillbilly persona, "Red Hot Red", playing a straighter country style, and settling on "Les Paul" for his jazz performances. By the late thirties and early forties he was accompanying major stars of the time such as Judy Garland, The Andrews Sisters, and Bing Crosby, and having hits with his own Les Paul Trio.

The Log – Les Paul Invents The Electric Guitar

Paul, at heart a showman who wanted his guitar to be the loudest thing on stage, realised that to avoid feedback he needed an instrument that – unlike the huge resonating chamber that is an acoustic guitar – didn’t resonate at all. With his gleeful mad scientist’s disregard for convention, he acquired a slab of four by four lumber (in some accounts an old railway sleeper), attached a guitar neck and some pickups to it, and took it to the stage.

Paul approached Gibson with his "Log" design several times throughout the forties, but the company repeatedly turned him down. "They laughed at me for 10 years," he later recalled. "They called me ‘the guy with the broomstick with the pickups on it.’"

In fairness to Gibson, it certainly required a leap of the imagination to see Paul’s Log as the future of luthiery.

Les’ Log

Paul’s close friend, engineer Leo Fender was the first to properly exploit Paul’s ideas in the Fender Broadcaster (later renamed the Telecaster) in 1949, a runaway success which galvanised Gibson into action. There remains some controversy about who designed what, but the Les Paul as we know it was mainly designed by Gibson in-house, incorporating Les Paul’s ideas, who the company then sought out for the right to use his name. After requesting a few alterations and finishing touches, Paul agreed.

By this time, however, Paul had already moved on to the first experiments with multi-track recording, triggered by his old boss Bing Crosby.

Overdubbing – Les Paul Invents Bohemian Rhapsody

Crosby was the biggest radio star of the era, and wanted a way to pre-record his shows; radio was still mostly live, and disc recording was considered below broadcast quality. Crosby himself had no idea what the solution was but had the connections and the money to put the right people together.

Jack Mullin of the US Army Signal Corps had acquired (or stolen) two Magnetophon reel-to-reel recorders from the collapsing Nazi Germany in 1945 and reverse-engineered (or ripped off) the design, before hawking it around Hollywood looking for a backer. The sound fidelity of the device was astonishing, and by sheer luck, Mullin’s second demonstration was seen by Murdo MacKenzie, Crosby’s technical director, who immediately put the two men in touch.

AEG Magnetophon

Crosby, impressed with the technology, invested in $50,000 in the Ampex company, appointed Mullin chief engineer, and set the company the task of cranking out tape machines. However, his real master-stroke was simply to give one to Paul to do with as he wished.

"I looked at the machine and all of a sudden the light went on", Paul later recalled. "What if I put a fourth head on this machine?" With his knack for being the first to spot what later seems almost trivially obvious, Paul realised that an extra playback head placed before the record head meant you could listen to what was on the tape at the same time as you recorded, giving you a new combined recording of both performances. You could also do this as many times as you liked, building up huge choirs from a single singer, or entire armies of guitars with a single player.

He also realised that this trick could be combined with changing the speed of the tape while recording, in order to create complex layers of otherwise impossible speeds, pitches and tones from his guitar. Immediately, he recorded and released the then staggeringly futurist jazz instrumental ‘Lover’ in 1948:

Using this same modified tape machine, Paul recorded a string of hits with his wife Mary Ford, most famously ‘How High The Moon’, which topped the Billboard charts for nine weeks in 1951.

"The first thing that was recorded was me just rapping on the guitar. I turned the volume up and hit the strings, no chords – that was the rhythm and it set the tempo. Then the second thing that went down was just chords. This went on and on and on as I built it up, part after part, take after take."

The Les Paulveriser – Les Paul Sort Of Invents Sampling

By 1950, Paul’s reputation as a technical wizard was central to his public image, and was often the central thrust of his NBC radio show. Indeed, many of his early fifties hits with Mary Ford were originally recorded almost as how-to guides to overdubbing for the show, before being later released as singles.

Listening back to the show now one finds a curious mixture of wholesome 50s domesticity (Paul and Ford recorded mainly at home) and crackpot futurism:

PAUL: Mary, I got a hunch that if I could take one guitar and make it sound like six guitars, I can make your voice – my wife – sound like six people.

FORD: That sounds like my husband – he eats like six people.

PAUL: But I’m your husband.

FORD: Which reminds me – if you don’t get a screwdriver and put that plug back in the electric stove… well, no cookin’.

PAUL: Oh, you don’t mean that all I’ve got…

FORD: I can’t give you anything but love.

PAUL: Well, that’s our cue for the next song.

Songs would typically be introduced in such cornball fashion, leaving the listener entirely unprepared for the sound of multiple overdubs of a single voice singing in close harmony – a sound previously unheard by the human ear and essentially the middle bit of Bohemian Rhapsody 25 years early – before building up to the complete production:

Over time, however, Paul found that while showing the audience his magic tricks was the heart of the show, what he and Ford were doing was increasingly so technical and cutting edge that it was difficult for many listeners to grasp.

To resolve this, Paul fabricated an entirely fictitious device called the "Les Paulveriser". Whenever a new method or piece of technology required too egg-headed an explanation to keep with the show’s homely feel, he would simply explain it away as a previously unseen feature of the Paulveriser.

Ever the showman, he realised that the Paulveriser gave him both a means to simplify his explanations to an audience while also employing clever illusions to keep imitators guessing, and incorporated a fake guitar-mounted device into his stage performances:

In reality, the various tracks heard in the performance were pre-recorded, with the Paulveriser simply being a remote control to stop and start the tape machine hidden offstage. Most audiences weren’t technically sophisticated enough to work out the trick, though Paul once recalled: "I still have the letter that Richard Nixon sent me, describing how Eisenhower had stopped him down in the tunnels beneath the White House and said, ‘You know, that Les Paul is bothering me. I still can’t figure out the Les Paulverizer.’"

Delay – Les Paul Co-Invents U2’s The Edge

Paul’s next realisation was an almost comically simple adaptation of his overdubbing method, as he related to Sound On Sound magazine in 2006:

"Every Friday night this guy Lloyd and I would sit in a saloon and watch the fights on TV, and one time he asked me to explain what I was after in terms of echo, and when I said like a guy shouting ‘Hello’ in the Alps and hearing it come back to him multiple times, he said, ‘You mean, like if you put a playback head behind the record head?’ Oh my God, we were out of that saloon so fast. We left the girls there with 10 dollars to pay for the beer, we forgot all about the fights and we were on our way home. It took us 10 minutes to get there, and we had that thing up and running in no time at all. We quickly realised that by moving the playback head forwards or backwards we could also change the delay – the whole neighbourhood could hear ‘Hello… hello… hello…’"

"Sel-Sync" – Les Paul Gives Birth To Modern Music, Which Appropriately Does More Or Less Nothing Until It Becomes A Teenager

There was one problem with Paul’s tape overdubbing method; when building up layer after layer, one mistake would ruin the whole production, and with each new layer, the sound quality progressively degraded.

"[I realised that] recording using sound-on-sound was crazy," Paul recalled. "There’s a better way: Stack the heads on top of the other — 1-2-3-4-5-6-7-8. When I told my manager, ‘I think it will change the world,’ he told me I should do something about it."

The device Paul imagined was beyond his engineering skills to build, so he took the idea to Ampex in 1953, who after two difficult years and many false starts, finally sold Paul back the first "Sel-Sync" 8 track recorder for $10,000. As with the Les Paul guitar, there is some controversy over who precisely came up with what, and it must be noted that Ampex Special Products manager Ross Snyder was heavily involved in the design.

The device was incredibly radical, but multi-track recording was, for a long time, simply used to capture live instruments in isolation from one another, or to enable vocalists to later dub on a vocal track after using a couple of tracks to record a backing in the emerging stereo format. Indeed, nobody was to really pick-up the thread Paul had started until the late 60s studio based experiments of The Beatles and The Beach Boys.

If anything, this shows that this is not really a story of gadgetry, but rather one of Paul’s boundless imagination and the drive to realise his musical visions.

"I often wished that Les would have made a greater success with the [8-track] machine," Snyder said later. "[But] he never had a hit again. By 1955/’56/’57, when Les was using the new machine, rock ‘n’ roll had taken over and he was not a rock artist."

Paul himself appeared largely indifferent to his shrinking profile, continuing to play circuit. He retired at the age of 50 in 1965, but later returned to live performance in the mid-70s, and played weekly right up until his death. Speaking in 2005, he remained modest about the significance of his contributions: "If it wasn’t for Bell Labs, I wouldn’t have been singing into their telephone, and if there wasn’t an Edison, there wouldn’t be a phonograph. If I didn’t have those things to play with, like the telephone receiver I put underneath the strings of my guitar and plugged into the grid of my mother’s radio, it wouldn’t have happened. I was just lucky enough to have others that had done so much who deserve so much credit."