“JOE was a flawed character,” says Johnny Green, almost ten years to the day since Joe Strummer’s untimely death on December 22, 2002. “He struggled at times to make sense of his own private life, his relationships didn’t always go swimmingly, and he wasn’t always that clever about the decisions he made in his own career – look at The Clash’s history, and the major part he had to do with its collapse.”

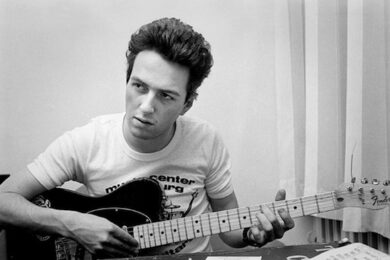

Myth blurs the reality behind pop’s polemic voices, and the popular antidote to Strummer’s legend is his privileged upbringing and private education.

But for the singer, Green insists, it wasn’t the irreconcilable millstone that’s been hung round his neck.

“I don’t think he struggled with that part of his past, no. I think other people struggled with it. He threw that off his back when he left home and tried to become the man he wanted to be.

“None of us can choose the life we’re born into,” Green adds. “Joe believed that rock ’n’ roll – going right back to Gene Vincent and Elvis – is the medium of reinvention.”

A decade after the frontman died suddenly from an undiagnosed heart condition, the Clash roadie is reflecting on a friendship with the complex man behind the myth.

“He blamed himself for the breakup of the Clash until the day he died,” he says. “I’d go round to his house and he’d be beating himself on the chest like Tarzan, calling himself an idiot and saying it was all his fault.

“Joe said afterwards that they might have just taken a bit of time out, cooled down a bit, because they worked frantically. They never went on holiday – they didn’t even have Sundays off. It was non-stop.”

Today, drummer Topper Headon’s heroin addiction might have been handled with more sympathy.

“Joe was very tough, right back to ’76 in saying that they weren’t a druggie band,” Green adds. “The thought that he might have someone on his hands who might be that way brought shame on the inner Joe.”

Johnny was the band’s road manager from 1977 until 1980, when, at the height of their powers, he left to move to America.

“The Clash were getting a bit predictable,” he says. “I preferred the chaos of the early days. I appreciated the more sophisticated stuff, but being on the road was so unpredictable.”

When he moved back to London a year later, there had been a shift in the way Strummer was perceived.

“People were already seeing him as some kind of spokesman. He wore that hat very reluctantly – he didn’t want to be that sort of bloke. He wanted to be in a successful band, of course, but he still wanted to have his regular life, he didn’t want to be isolated from that.

“In many ways he was a more opened up man, because he’d done more. But he didn’t just want to play the rock star – that’s why I liked him. People were trying hard to not let him be grounded. They’d treat him like a star wherever he went, and he didn’t particularly want that, much as he wanted them to like his music."

They were two sides that Strummer struggled to consolidate. Green witnessed the scattershot approach to both his personal and work life.

“Joe wasn’t a very organised man,” he says. “He had this knack of crawling behind amplifiers or strange bits of venues before the doors opened, and you’d find him scribbling away on little bits of paper.

“He’d write ideas down as soon as he got a quiet moment, and then he’d stuff them into plastic bags – he never carried a case with him. He’d get into a hotel room with about six of these supermarket carrier bags, tip them all out on the floor and then root through them like some bag man going through a skip, saying: [gruff Strummer voice] ‘where did I put that bit of paper?’”

It was a shambolic chaos that worked for the lyricist. As one of the band’s inner circle, Green was privy to the mechanics of the Strummer-Jones songwriting partnership.

“It worked on affection and competition,” he says. “While they were really fond of each other and close to each other, like the best love affairs it could spark up with passion at times. It could spill over in any direction – it was strong emotions. It wasn’t cool and calculated.”

Even at their height, the Clash shunned entourages for a small, tight-knit team. In his days on the road, Johnny drove the band in a car, while fellow roadie, the Baker followed in a van with the gear.

“Who sat in the front seat? Always Mick Jones. He had a reputation in those days, and the others would laugh and call him a diva. It was like a group of unruly children. You forget how young they were back then and I was three years older. I was the old man – mid-twenties.

“They would be joshing, getting bored very easily, wanting to stop at the services, mess about, drink cups of tea. It wasn’t a wild rock ’n’ roll lifestyle. They’d take it in turns to play music over the stereo, educating each other about new music they’d discovered, always talking, reading the newspapers and swapping stories. It was a pretty interesting place to be.”

In 1986, after a drawn out disintegration that saw Headon and Jones axed before a gang of rent-a-punks were drafted in, Strummer found himself sans band and in a desolate place artistically.

“You might call them lost years,” reflects Green – “But he kept his hand in, working with the Pogues, Earthquake Weather, and he did a couple of films. Quietly he was always helping other musicians, which never really comes out.”

Strummer slipped into an alcoholic fug that he would not shake off until he re-found his muse with the Mescaleros, more than a decade later.

“It did make him emotional, drink makes you lose your inhibitions, and when you’re confused they come out. Joe was aware of what had happened, and in his view he’d blown it. He thought he’d made the Clash fall apart, that’s how he saw it for a long, long time – for the rest of his life, in fact.”

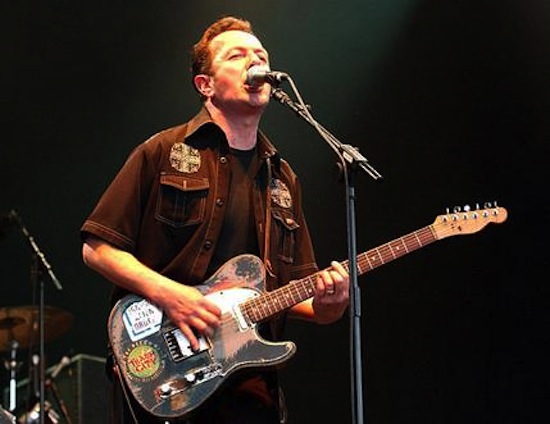

In forming the Mescaleros in 1999, Strummer went full circle and reconciled the ‘Year Zero’ manifesto that had seen him turn his back on everything and everyone from his life pre-1976. He reunited with musicians from his pre-Clash pub rockers, the 101ers.

“I think it was very important for Joe in the end. He’d severed all links with the people from before he got into punk rock. Anyone from before then, he didn’t want to know, he cut everybody dead. As part of his reinvention as Joe Strummer he didn’t acknowledge the man he’d been before that.

“Eventually he came round to realise that they were good people. It was time to pick up and make up. That was an important factor in all that.”

There was a palpable change in the singer’s demeanour, which became more considered – while still retaining the insecurities he’d harboured his whole life.

“He was more of a reflective man at that time. He was still feeding the inner man – he was reading, thinking, talking, and I think that period gave him the chance to do that, and to work on his music.

“He was delighted to be back in music. He was not a top-notch musician – he had to work at it. I think he was always self-conscious about that. If you play day-in, day-out alongside Mick Jones, who is a consummate musician, it will do that.”

While the Mescaleros were a form of catharsis, Green dismisses any suggestion that Strummer found peace in the last years of his life.

“I’m not sure he was a very peaceful sort of guy. He was always pushing himself in different directions. He was musically curious, philosophically interested and politically motivated.”

The crowds at Mescaleros gigs inevitably wanted to hear Clash songs. It was another dilemma for Strummer.

“He struggled with that. When he was playing with the Mescaleros and people were shouting out for Clash songs. He was always in two minds about it: ‘people want to hear that stuff,’ he’d say. ‘But on the other hand I’m out here making music with my new band and I want the public to hear it. This reflects me as a slightly older man.’ In the end he recognised those songs were part of his persona.”

The perfect bookend to the legend persists, but Mick Jones’s surprise cameo with Strummer at the firemen’s benefit concert at Acton Town Hall on November 15, 2002, was not the Clash frontman’s last. That came in Liverpool, a week later, on November 22.

“I wasn’t at the Acton gig,” says Green, with a trace of regret. “But the thing with Mick certainly wasn’t planned, it wasn’t orchestrated at all. It was instinct and impulse. In fact, one of Strummer’s great phrases was ‘instinct not intellect’.

“I’d been with Strummer about a week before, down in Hastings. He played down on the end of the pier, and I thought for no good reason I’d go. I remember that gig for being a bit of a shit-hole. I spent the afternoon with Joe, and save for the gig in the evening that was the last I saw of him.”

That Strummer and Jones should encore with ‘White Riot’ in Acton was telling. The only time Strummer ever used his fists came some 20 years earlier, when his writing partner refused to go on stage to perform the same song, citing its racist misinterpretation by some of the less intellectual sections of the crowd.

“That was the only time I ever saw Joe use violence,” says Green, “and he did smack him a thumper in the dressing room. It was at the Sheffield Top Rank. But doesn’t it say a lot about team-work that within a minute Mick had dabbed himself up, strapped his Gibson back up and he was out there.”

That the relationship should have been reconciled the last time the pair played together was a fitting epitaph.

“It’s great that Joe still means something to people down the years,” says Green. “He told it straight, he said what he thought. He didn’t try and couch what he was trying to say for his own public image. Particularly in the early days what he said was not always acceptable, and I think people respect honesty and truth.”

But Green sidesteps any political hyperbole for the crux of what he cites as Strummer’s enduring legacy.

“His legacy is that he showed people that you can have a bash at whatever you try: don’t feel intimidated by it, give it your best shot, whatever your dream is. And secondly he always thought that you should question authority, think for yourself, figure it out. What he really said – and what was printed on his coffin was, ‘question everything’.

It’s no surprise that for the affable Green, memories that loom largest are not of the chest-beating, sloganeering idealist, but of a complicated, energised friend.

“It was his joy of life, he loved doing what he did. He was great company. Before a show, after a show, and even during a show he was so alert. Never bored with what he did, and thus a very good man to be with.”

Green went on to write a memoir about his time with the band, before developing a taste for cycling and writing a book on the Tour de France.

“The last time I saw Joe, I told him about my passion for the Tour de France, and he said, ‘What a great idea! That sounds terrific. I’m really busy until Christmas, but come and see me in January and we’ll do it together.’

“He really encouraged me, and then the bastard went and died on me. So I though fuck it, I’m going to do it anyway. Even in death what he’d said inspired me to continue. He was a bundle of energy and encouragement.”

A Riot Of Our Own: Night And Day With The Clash by Johnny Green and Garry Barker is out now, published by Faber