Late in 1988, in a studio in west London, a 19-year-old by the name of Jonathan Saul Kane dropped the needle on a copy of ‘The Recluse’ by UK funk group Cymande, snatching a sample of vocalist Jimmy Lindsay crying out, “will the darkness come to set me free, and comfort me?” Cymande disbanded soon after the release of their third album Promised Heights in 1974, and would remain unsung heroes for nearly 50 years, but here they were repurposed nearly a decade and a half later on the inaugural release from Kane’s Depth Charge project.

Kane weaved Lindsay’s haunting vocal refrain into a tapestry of thundering drums and gut-wrenching sub bass, all bookended with dialogue ripped from a VHS copy of Shaolin Thunderkick by kung fu-schlock director Godfrey Ho. The eponymous ‘Depth Charge’ dropped on an epic eight-minute 12” in January 1989, sitting snugly on record shelves next to the likes of Coldcut and Fresh 4, but while it caught the ears of kids who were into the UK’s burgeoning beat scene, it was a much darker offering than the dreamy dub-soul coming out of Bristol or the cut-n-paste jams on London’s eclectic dancefloors where you might’ve found Kane himself tearing up the decks at clubs like The WAG or The Mud Club at Heaven.

“I got him to do a DJ spot at The Mud Club straight after hearing him play” reminisced Mark Moore in a Facebook post about Kane yesterday. The soon-to-be S’Express star had befriended Kane after meeting “randomly in the street” and was soon blown away by his DJ skills back at the young producer’s flat. Likewise, Kane’s friend and DJ partner Tim Simenon enlisted his turntable techniques for the album version of ‘Megablast’ on Bomb The Bass’ debut LP; so Kane was already in the charts in 1988, cutting up Fab 5 Freddy’s classic “fresh” sample before he’d even made that first Depth Charge record. In fact, that same year, under his DJ pseudonym Grimm Death, Kane released his debut single alongside rapper Joz One on a label which was run from his local record shop, Vinyl Solution on Portobello Road.

For a couple of years, Vinyl Solution had specialised in punk and metal, releasing the likes Bolt Thrower, The Stupids and Les Thugs before Kane delivered his clattering hip hop cut ‘Too Tuff To Rip’ which lifted its loping bassline from Jimi Hendrix and Curtis Knight’s ‘Happy Birthday’, beating the Beastie Boys to the sample-punch by almost half a decade.

Vinyl Solution soon became a home to a succession of Kane’s guises. Depth Charge continued to explore cinematic beatscapes while The Octagon Man summoned ‘The Demented Spirit’ of the recently banished electro sound. As TET, Kane explored house, and ‘Help’ by The Spider was spun in raves across the land, the latter a collaboration between Kane and Ian Loveday who also rocked raves with the Dune sampling anthem ‘Spice’ by Eon. Even UK electro-funk legend John Rocca teamed up with Kane for a handful of tracks under Rocca’s Midi Rain guise. It’s safe to say that at the turn of the 90s, our hero with a thousand faces was heavily in demand before he’d turned 25, even being offered the opportunity to work with Kylie Minogue at one point. “It could’ve been interesting,” Kane admitted during an interview for Breaking Point mag in 2000, “however, I copped out.”

A reluctance to pursue the obvious, or take a commercial route through the industry informed Kane’s spiralling career since the early days, but it’s also why he’s not a household name. When Mo’ Wax exploded as the 90s progressed, and “trip hop” became a throwaway term for the exact kind of dub-infused beat-abstractions which Kane had pioneered at the turn of the decade, he still hadn’t put his name to a dedicated album, favouring a scattering of 12”s until Vinyl Solution finally closed its doors in 1994. “Vinyl Solution had done its thing; run its course,” the producer assured Siobhán Kane in a 2008 interview. “It had reached a hundred [releases] so it was a good time to kill it off in legendary fashion.”

One of Vinyl Solution’s final offerings was the long-awaited Depth Charge LP Nine Deadly Venoms which collected (almost) all the 12”s from the past 5 years, augmented with a handful of new tracks. The album could’ve marked Kane as the godfather of this sound, but instead it hit the shops alongside a stack of trip hop classics including Mo’ Wax’s Headz comp, and in the thick of Wu-Tang fever, leaving Kane’s brand of Kung-fu-horror-dub-hop sounding less fresh to newer, younger audiences who weren’t aware of all he’d pioneered. The producer remained modest in light of his own past glories, however. In an interview for NME in 1998, Kane was quick to rebuff the notion that Wu-Tang might have bitten his kung-fu style: “If that’s the case, you might as well say I nicked Lee “Scratch” Perry’s ideas. He was doing it years before any of us.”

A deluge of trip hop aside, Nine Deadly Venoms maintained a healthy underground following, and the next step was Kane’s own DC Recordings which launched in 1995, soon devastating dancefloors with the Depth Charge 12” ‘Shaolin Buddha Finger’, ramping up his trademark kung-foolery with go-go drum fills and an infectious breakbeat, garnering the dubious accolade of being proto-big beat, which of course Kane hated.

Mostly, DC Recordings’ output explored Kane’s obsession with experimental music and fuzzy old films from the back alleys and bargain bins of horror, soft-porn and martial arts. Inevitably he began releasing them himself via the Made In Hong Kong video imprint which released various “heroic bloodshed” movies for the first time in the West from the likes of Benny Chan, Stephen Chow and the infamous Shaw Brothers whose SB logo Kane reappropriated for DC Recordings.

The label would continue for another 15 years, signing suitably strange approximations of beats and breaks, like the echo-drenched synth bounce of Kelpe, the go-go adjacent Arcadian – Kane was a massive fan of Trouble Funk – and the psych-boogie of The Emperor Machine, aka Andrew Meecham from Kane’s old Vinyl Solution labelmates Bizarre Inc. Meecham also released a dub-laden punk-funk album on DC alongside his Bizarre Inc cohort Dean Meredith under the name Big Two Hundred, a disfigured cousin to their more dancefloor friendly mutant disco project, Chicken Lips.

Kane continued to record and release his own material too, with a brace of Depth Charge LPs, a trio of increasingly synth-heavy outings from The Octagon Man, and his Alexander’s Dark Band project which took the baton from Depth Charge’s murkier moments like ‘Dead By Dawn’ and ran with it for three albums, albeit pretty slowly.

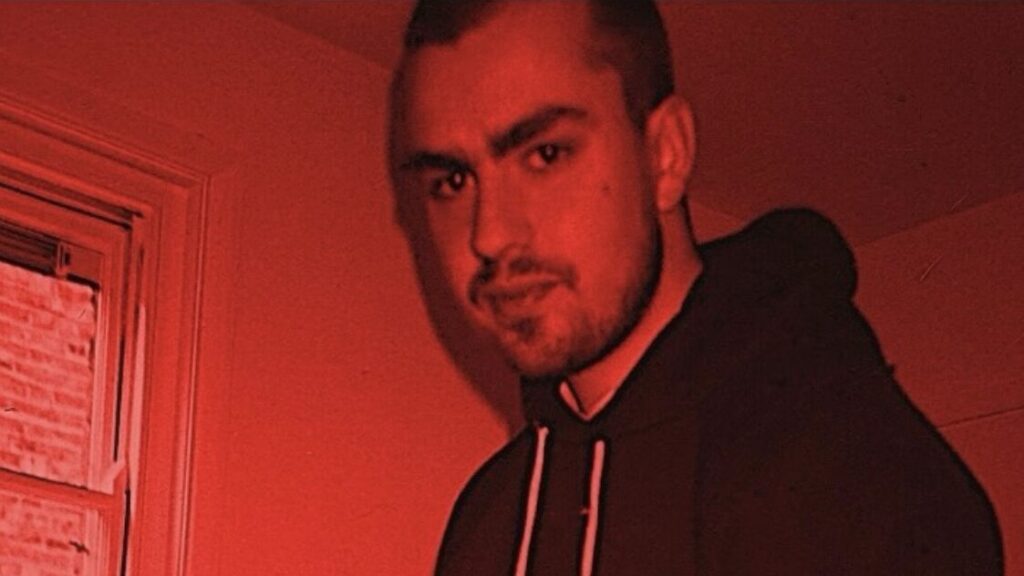

In recent years Kane’s once relentless musical output ground to a halt. Like Cymande who he sampled back in 1988, Kane remained an unsung hero to a handful of faithful fans, but to most he was barely a footnote in the annals of UK music. Had he not been so prolific online – if a bit curmudgeonly at times – it would be easy to imagine he’d drifted into obscurity, never to be heard of again. Instead Kane shared amazing photos he’d take around his West London neighbourhood, and chatted about his favourite analogue studio gear, underappreciated old records and movies, and could often be found arguing on football forums.

It was noted, when the awful news of his passing arrived on Monday, that folks in Kane’s internet circles hadn’t heard from him for a few weeks. Old friends described him as a bit of a hermit in recent years, battling health issues, though he was apparently working on new material not so long ago. The details of his death have not yet been announced, but I wish his friends and family all the best at this horrible time, and I hope the collective outpouring of love for Kane sets them free and comforts them.