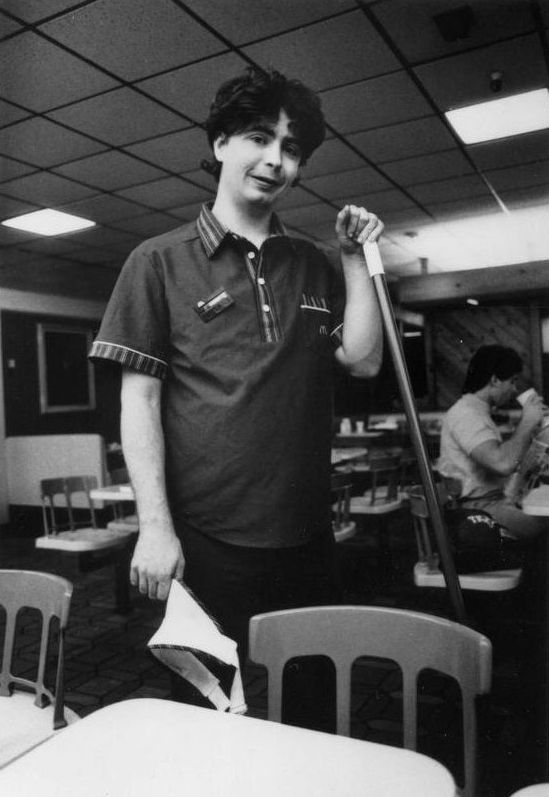

Homestead Records publicity photograph

Musicians die all the time, and if you like their work, it always hurts a little. If you care at all about popular music, or just have friends who do, chances are your social media feeds are chockablock with nostalgic photos of some fallen icon every week or so. Some of this mourning may be performative, even opportunistic, but most of us smash the like button, listen to a song or two by the artist, and carry on with our day.

Daniel Johnston’s death feels different. At 58, he was too young to leave us, but not in a particularly romantic or surprising way; he died of natural causes, probably rooted in a combination of poor diet and difficulties with medication. It was long known that he was not well, physically or mentally. In the 2005 Jeff Feuerzeig documentary The Devil And Daniel Johnston, then-recent footage found Johnston heavily medicated and lumbering around the family home; it was a portrait of a man placated and surviving, but to say he was thriving would be a stretch. While it may sound insensitive to say so, an early passing seemed a foregone conclusion, and not because Johnston fulfilled any "live fast, die young, and leave a beautiful corpse" cliche… he was just a sad, unhealthy guy.

It is Johnston’s music more than the man himself, then, which makes the loss feel so unique (not to take away, of course, from the friends and family who are grieving). Albums like Yip/Jump Music and 1990 are portraits of a flawed human with decidedly limited technical acumen striving to bring you the best he could muster, and this has often inspired others to find the best in themselves. Hearing a man who’d been dealt such a lousy hand (albeit by fate and his own choices more than by anyone else) pull out something as pure as ‘I Live For Love’, and sing it with such unflagging sincerity, has a way of sparking one’s own sense of hope.

The profound intimacy of Johnston’s early home recordings (combined with the fact that, for years, the easiest way to get them was to mail-order handmade cassettes directly from his sometimes-estranged manager) also make the music feel like it truly belongs to the listener. It’s hard music to enjoy with others; the sound is so lonesome, in fact, it almost hurts to listen if you’re not feeling roughly the same way yourself (working in record stores, I’ve regretted every single attempt I’ve made to play Johnston’s music over the house system).

Personally, I probably wouldn’t be here were it not for Daniel Johnston’s music. When I was 21, I went through my first adult breakup, and was facing my first serious bout of suicidal ideation. Having been fairly sheltered growing up, and being about seven years off from being officially diagnosed as mentally ill myself, I didn’t take it very well; in fact, I had a nervous breakdown, and could hardly function for weeks. I spent more than one evening sitting directly in front of my stereo, listening to cassettes of Hi, How Are You and especially Yip/Jump Music on repeat, feeling that it was the only relatable music in the world. Feeling this, while knowing that Johnston struggled with mental illness, was terrifying to me, but I had no choice. It was the only balm for my battered, inexperienced heart.

I tell this story not because I think it’s unique, but because I know it’s not. Lots of hurt, lonely, ill people have been helped through lows in their life by Johnston’s music. It’s horrible that his music always came from such a painful place, that it was made by someone who had such a difficult time trying to function in the world. This, however, was also what made it work for everyone who ever needed it. Whether he knew it or not, Daniel Johnston’s songs, and the struggles he went through to write them, were his gift to a universe that needed them.

Since Johnston was mentally ill, and since his most famous songs weren’t performed or recorded in a way that one would call conventionally proficient, there have been cries of exploitation since the beginning of his career. While some of those naysayers meant well, most of them were just callous and unimaginative. Sure, there were and are people who’ve listened to Johnston’s music to poke fun, for novelty. There are also thousands of people who’ve deeply connected with it not because of, but in spite of, the fact that the guy couldn’t play guitar worth a damn. They could hear and feel the music that was in Johnston’s heart, whether he could make it come out the same way or not. Daniel loved the attention, and they loved the songs; the only thing truly getting hurt in that exchange was some casual observer’s pedestrian sensibilities.

Though he was often surrounded by people who loved and cared about him, Daniel Johnston lived a hard life. His condition made it harder for him not to hurt those same people. The path to his passing was a slow, sad, mostly downward spiral. Still, in his music, Daniel Johnston rarely stopped looking up, knowing in his battered heart that true love would find you, all of you, in the end. Whatever you believe happens after we shuffle off this mortal coil, I hope that true love has finally found him too.