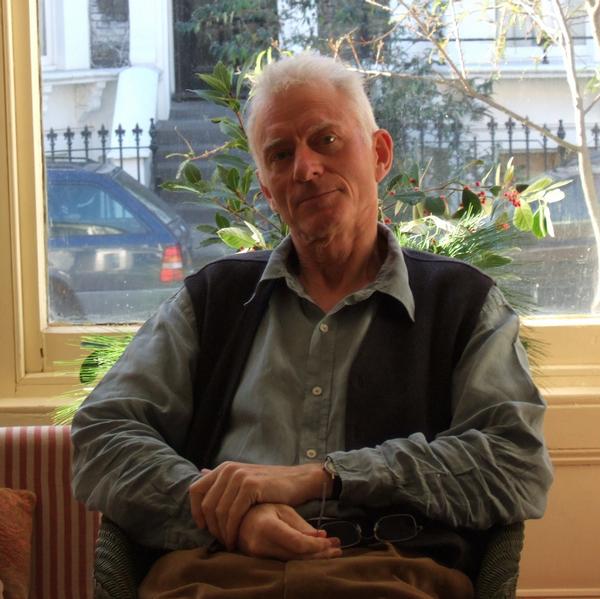

Charlie Gillett (February 20th 1942 – March 17 2010)

If John Peel is, rightly or wrongly, regarded as the most important music broadcaster of the last half-century, it would be wrong to think he was operating in a field of his own. Charlie Gillett, who died last week after a long illness, was just as dedicated to educating his listeners and changing attitudes to what constitutes good radio; a relentlessy curious and intelligent DJ working on the broadest of canvases, he was also a dyed-in-the-wool fan who relished sharing his enthusiasms.

At the same time as Peel’s late night Radio One show was an important springboard for punk rock and the increasingly fractured strains of indie music that followed, Gillett was providing an equally essential service on his Radio London show, Honky Tonk, oblivious to the constraints of any playlist. There may have been smaller quotient of surly white guitar rock, but Charlie’s shows embraced the unknown and overlooked from all four corners of the globe.

He brought cajun crooner Johnnie Allen’s version of Chuck Berry’s ‘The Promised Land’ to our attention (ultimately making the track available in the UK via his own Oval label), and championed African musicians like Youssou N’Dour and Salif Keita long before the slightly patronising term "world music" had entered the argot of the entertainment industry.

Gillett played demo recordings by the likes of Dire Straits and Elvis Costello before either had records in the shops. Writing on his website last week, Costello recalled Charlie’s role in giving him his broadcast debut: "I will always be grateful for those few curious minutes when I sat with my head cocked like Nipper the Dog at the improbable sound of my own voice coming out of a radio speaker."

It’s odd to write about music or broadcasting as Charlie’s "career", as it would be best described as his lifeblood since studying for an MA in popular music at Columbia University in New York in the mid-1960s. Returning to his native England in 1966, he worked as a college lecturer while contributing to magazines such as Record Mirror and Rolling Stone. In 1970 he published the book Sound Of The City, a seminal study of music’s cultural and social impact, as indispensible as anything by Greil Marcus or Peter Guralnick.

Gillett also flirted with management, taking Ian Dury’s band Kilburn & The High Roads under his wing and also aiding the early careers of Lene Lovich and Paul Hardcastle, while simultaneously scouring the globe for undiscovered gems to license to the aforementioned Oval label. Broadcasting remained his first love, however, although he turned down an offer to host the BBC’s grown-up rock programme The Old Grey Whistle Test, in favour of his own Radio London show that he felt would give him a wider remit and a greater opportunity to bring new sounds to the masses.

He switched to another London station, Capital Radio, in 1979, but when his show was dropped after three years a listeners’ campaign forced programmers into inviting him back. The BBC came calling again in the 1990s, with regular slots on both Radio 3 and the World Service. Just the appearance of his name in a listings magazine represented a badge of authenticity, a seal of quality that few broadcasters have ever been able to claim.

He was forced to retire in 2006 after contracting Churg-Strauss syndrome, a rare auto-immune disorder, but still managed, after treatment, to make intermittent programmes up until two months before his death. Charlie leaves behind a wife, three children and two grandchildren, not to mention thousands upon thousands of fans, both among the public and other industry figures. His passion, his articulacy, his knowledge and his influence is arguably best summed up by friend and fellow broadcaster Mark Lamarr, who described him as “the rock ‘n’ roll equivalent of Dickens or Shakespeare”.