When faced with having to sum up Bert Jansch’s life it is nigh on impossible to choose what to focus on first, as they do so summarily in those cursory opening lines of your regular obituary. Is his crowning achievement that wonderful slew of albums between his 1965 eponymous LP and 1971’s Rosemary Lane? His work with Pentangle? The fact he was a major influence on Jimi Hendrix and Neil Young? The album that accompanied his magnificent renaissance during last decade, The Black Swan? Or his devotion and warmth towards a whole generation of artists to emerge in the ’90s and ’00s who venerated him so much?

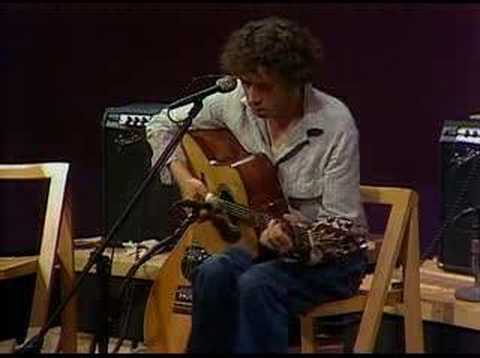

Ultimately, it’s enough to say that in his famously quiet, modest way, Jansch was one of the most innovative instrumentalists of the twentieth century in the folk rock canon – and there was so much more to him than tunings that influenced several generations and the astonishing clarity of his playing. And even as the fingers became a little less nimble and the voice more strained and frail, he was still a performer who never seemed satisfied with the vast knowledge he had gleaned. His desire to always see more was central to his humility, something to which artists such as Johnny Marr, Bernard Butler, Beth Orton, Meg Baird, Devendra Banhart and Vetiver will attest.

That quality went back a long way. When Jansch arrived in London from Scotland in 1964, he was already an aficionado of American blues forms, and soon became an authority on steadfastly traditional English folk as defined by Cecil Sharp’s archives. But neither of these things were really ever enough to contain him, as can be heard in the exploratory nature of his first couple of LPs, Bert Jansch and It Don’t Bother Me, both released in 1965. Another great guitarist on the London scene, John Renbourn, was listening closely, and the two made a pair of albums as a duo. Together they veritably revolutionised the harmonics of guitar playing.

Unlike the market-friendly rock and roll bands of the time, Jansch, like his friends the Incredible String Band, had a strong penchant for travel and shambled his way across Europe multiple times, as well as to North Africa. Along with opening his eyes musically, Jansch assumed the existence of the so-called beatnik, further distancing him from the ‘people’s music’ of the folk clubs, complicating his oeuvre even more.

Indeed, considering that period from the vantage point of today, in terms of image Jansch seems to pale in comparison to many of his peers. Without the poetic mystique of Nick Drake or the Byronic swagger of John Martyn, yet not quite as vehemently traditional as Martin Carthy, he was everyone and no one. Certainly, as with the likes of Davey Graham, Paul Simon and Ralph McTell, he trudged around the acoustic clubs of London and Glasgow, but even as a young man he could not be regarded as a folk circuit workaholic like Carthy. It’s fair to say that Jansch’s closest musical spirit, Renbourn aside, was probably another extraordinary visionary, Richard Thompson.

It goes without saying, too, that he had scant regard for an industry that had propelled to fame someone as depressingly throwaway as Donovan, who got hold of one of Jansch’s more direct political statements ‘Do You Hear Me Now’ and with it enjoyed substantial chart success. Jansch’s view of pop or rock acts interpreting his material is also reflected in his less than approving reaction to Led Zeppelin’s appropriation of ‘Blackwaterside’ for their first LP’s ‘Black Mountain Side’. The evolution of folk music is certainly about the sharing and swapping of songs and styles. But this, it seemed, was just exploitation.

‘Blackwaterside’, from the Jack Orion album, is one of Jansch’s greatest examples of re-interpretation, and to a degree, collaboration. He learned the song (a traditional folk song, performed by a number of different artists across the years) from the great enigma that was Anne Briggs, the reclusive, extraordinary acapella singer, whose shyness and eschewing of attention found a natural friend in Jansch in the early 60s. And his transformation of others’ songs extended famously to Jackson C. Frank’s ‘Blues Run The Game’ as well as Ewan McColl’s ‘The First Time I Ever Saw Your Face’. Jack Orion, an album of traditionals with Renbourn on board, still shows off Jansch’s powers at their peak in the late 60s.

But, of course, it was with the great democratic institution Pentangle that Jansch’s love of playing with others reached its zenith. Jansch, Renbourn, Danny Thompson, Jacqui McShee and Terry Cox were similar to one another in their daunting talent but again were gloriously lacking in a clearly marketable persona. Together they would prove anathema to the increasingly commercialised psychedelia of the late 60s and the bombastic rock that was about to ensconce itself in the mainstream. Certainly their songs were steeped in recognisable folk dogma, but there was plenty more to it, and improvisation was king.

“That was the thing about the band, it fitted in with your own abilities,” Jansch told me when I interviewed him in 2008. “You didn’t have to alter anything. And that applied to each of us and why we ended up doing solos in a jazz sense. Danny would take a bass solo, Terry would take a drum solo. We had room for that kind of thing. That didn’t happen in the rock school."

Pentangle allowed Jansch an ensemble outlet – and the space to further explore his interest in Eastern, archaic and American styles – that he had never had anywhere else before or after. Unlike many whose solo work is a mere facsimile of their main band, Jansch’s own music is unrecognisable from Pentangle’s five albums, of which The Pentangle and Sweet Child remain masterpieces.

During Jansch’s critical re-emergence over the past decade or so, the majority of his albums from the 70s and 80s were bypassed – partly due to their wavering quality (severe alcoholism taking its toll), but also because many, such as Leather Launderette, From The Outside and Thirteen Down, are yet to receive the loving reissue treatment that many other albums have.

But Jansch had already long been adopted by last decade’s folk revivalists by the 2006 release of The Black Swan, a record that afforded him unprecedented critical praise, and one that proves fitting as his final studio statement. His latter years also saw the release of the excellent compilation Dazzling Stranger, featuring arguably the finest version of ‘Reynardine’ ever put to tape.

I first saw Bert Jansch play at his own 60th birthday celebration concert in November 2003 at the Queen Elizabeth Hall. That night he had for company Marr, Butler, Orton, Graham Coxon and one of his personal favourites, Hope Sandoval of Mazzy Star. Roy Harper sat transfixed in the front row. In the years following I caught him at venues as grand as the Royal Festival Hall, but also as small as London’s sadly defunct Spitz. He also embraced the spirit of his new generation of admirers by playing at the Green Man Festival (solo in 2006 and with the reformed Pentangle in 2008). On each occasion he was composed and insular, quite physically bearing out his oft-repeated quote: “I’m not recording for anyone, just myself.”

Jansch was not above making the odd dud move – the 1982 Pentangle reunion was unfortunate for all involved, while he certainly endured his fair share of booze-fuelled wilderness years. But it takes a certain kind of person to attract the fawning adoration of someone as picky as Neil Young (they toured the US together in 2010). As unextravagant a person as he was seminal an artist, another pioneer from modern songwriting’s formative years shuffles on.