While it draws some odd looks, Tennant and Lowe’s materialisation in cyberspace is a pretty logical extension of the way videogames have smashed into young people’s everyday lives. Even as the Pet Shop Boys toured south-east Asia in 1989, Tetris for Nintendo GameBoy had people on the streets outside “seeing falling blocks in front of their eyes and mentally rotating real-life objects to get them to fit together.”

But Very does more than just chuck in a couple of Sonic references to look trendy. It borrows so heavily from videogames it almost starts to become one. It immerses its user in spectacular three-dimensional spaces; it has characters; it’s fun; it’s escapist; it reveals more the more closely you look; it has a narrative; you can play it. It even contains an Easter egg.

Of course you don’t really get to control it – but it does send you on a journey, and not just one created by its lyrics. It instils and satisfies a longing for abstraction, for space; somehow it mimics the sense, at once spectacular and sad, of getting further than you have before, of collecting something you thought would always remain out of reach, of being dangerously close to the final sequence, which will be both loss and reward and which cannot be repeated, not really, not so that you’ll feel this way again.

Before we grow up and learn what parts of our minds things belong in, back when a videogame or a song could consume us, take over our dreams and rewrite our source code – that’s the album’s timestamp.

Very is certainly immersive; Janet H. Murray’s use of the word “spatial” implies visual space, but might it not also apply to sound environments? For these are the computer screens on which the album’s narratives play out – soundscapes, if you like.

The Pet Shop Boys have treated music as a subgenre of cinema ever since ‘West End Girls’ somehow made a choir sample sound like a metropolis in bad weather. But Very’s more abstract sound creates more abstract digital spaces; they juggle photons halfway through ‘I Wouldn’t Normally Do This Kind of Thing’, proposition you on a sofa made of numbers during ‘A Different Point of View’, surf the clouds into infinity at the start of ‘One in a Million’.

They switch from celluloid to CD-ROM and make every spike and every shadow marvellous because you don’t know what you’re looking at anymore.

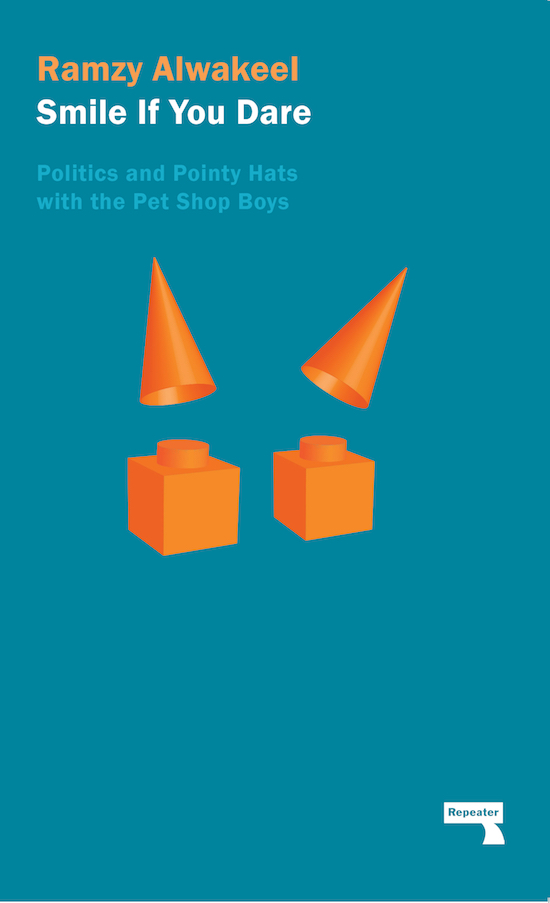

Very’s “graphics” sound like the building blocks for a dream, and don’t videogames share a certain dazzling logic with dreams?

The word is “liberation.”

It’s making your way home on a Friday afternoon over impossible shimmering vistas, past giant spinning tops and through streams of tiny cubes that behave like shoals of fish.

It’s experiencing the sublime, staring up at giant Cold War structures that may or may not have the Pet Shop Boys’ profiles when viewed from a certain angle.

It’s turning into a cybernetic eagle, soaring over this unreal kingdom and headlong into the vanishing point.

Smile If You Dare is published by Repeater Books