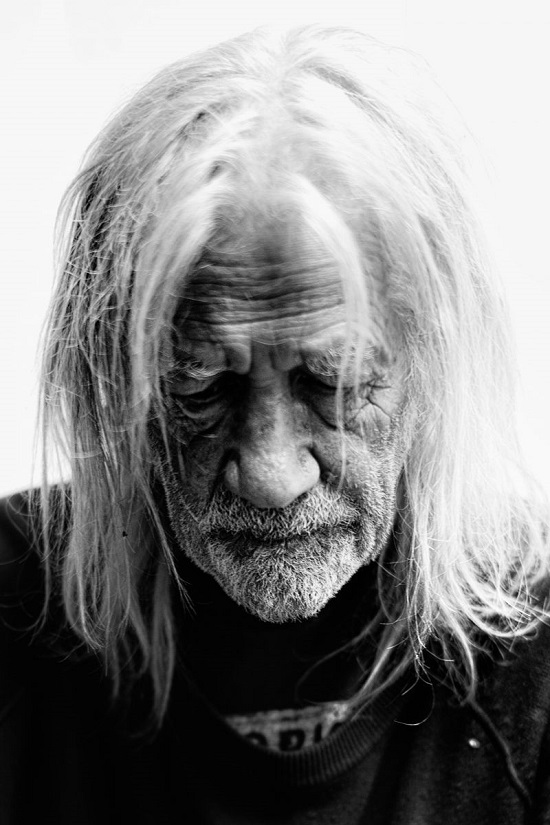

Penny Rimbaud, from his time as a founding member of Crass to the present day, has made many powerful statements in his career as an artistic outlier. His latest, however, is among his most completely compelling.

What Passing Bells, Rimbaud’s new album to be released via One Little Indian this November, has the war poetry of Wilfred Owen, who served and died in the First World War, performed with uncompromising intensity by the artist and set to harsh progressive jazz from pianist Liam Noble and cellist Kate Short.

It’s a vehement experience, with Rimbaud throwing himself into an evocative and emotional reading over unnerving interpretative backing. Live, it’s no less severe, and Rimbaud has taken a personal vow to perform it as many times as he can during the centenary of the war.

In the interview below, Rimbaud takes tQ through his longstanding relationship with the subject of war, from Crass’ Yes Sir, I Will to encountering Owen’s brilliance through Benjamin Britten’s War Requiem. Rimbaud’s new release is also the subject of a new short film by Noisey, which you can also see below.

tQ: You were born during wartime, and your father fought in the Second World War. How are your earliest memories shaped by war?

Penny Rimbaud: The first year or so of my life was spent under the kitchen table sheltering from the bombs. I didn’t know my father until I was 3 or 4 so I was never able to get close to him, I was only beginning to have some form of cognitive mind before he turned up, and I didn’t like him because he took me away from mum. It made for a strange relationship. Like most men who came back from the war he didn’t like to talk about it, so I never knew anything about him or why I hadn’t known him. He had to deal with his own pain, but sadly it transferred itself to me.

I remember I was about 6 or 7 when I took a book out of my parents library. It turned out to be pictures of concentration camps, I remember seeing this picture of the pits in Auschwitz and thinking, ‘well if that’s the world my father represents then I want nothing to do with it’. I didn’t know whether or not he’d been doing that, I knew he’d been in Europe. What makes it horrific when you’re a young kid is that there’s a tendency not to ask. As I matured I began to understand, but it created a picture that I detested. War kept you from your father and it kept you from yourself, it’s a selfish way that young kids think but that turned into a genuine, profound distaste for war, and the real world that my father was always telling me I had to grow up to be a part of.

Until now with What Passing Bells, probably your best known piece of anti-war work is Crass’ Yes Sir, I Will. How has your approach changed in the intervening years?

PR: Only in presentation. The ideas remain pretty solid, I always believed in what I call ‘appropriate action’, in other words acting according to the moment. I think that what I did during Crass was appropriate in the sense that the form in which my remarks took in the late 70s early 80s was appropriate because it was a revolutionary moment, we certainly believed there was a possibility of pushing through it to some sort of genuine socialist revolution, something that would overthrow the whole form of governance. It might seem naïve now but it’s certainly what we believed then. Yes Sir, I Will was a part of that.

I recently did Yes Sir, I Will again in 2014, I rewrote it from a Daoist viewpoint, and certainly a viewpoint inspired by John Lennon’s ‘All You Need Is Love’. That’s never been far from my heart, but how I express it through my thinking and actions is another matter entirely. To go out on the road with something like Crass’ version of Yes Sir, I Will right now would be inappropriate and irrelevant, even though what it has to say is more relevant now than it was then, that doesn’t matter. How we alter the course of affairs is important, and at the time that passionate anger had some sort of anger and resonance. Now I think it would be laughable, or as laughable as things like Antifa.

Why do you see Antifa as laughable?

PR: I don’t think you can oppose like for like in that way, never ever. Violence never quashed violence because if you’re equipped to do violence then you’ll continue that passage. Let’s say Nazis, if Nazis they be, have got a profoundly ugly form of thought and of actions, why match that? Antifa’s ugliness is no better than the ugliness of the far right.

Your first contact with Owen’s work was through Britten’s War Requiem, how did you come across that?

PR: I was a chorister, I performed the first English performance of ‘Spring Symphony’, and Britten conducted it. I don’t know how old I was, maybe 10, [Britten] seemed very kind, and it was certainly great working under his guidance. That gave me an attraction to his work. I don’t know how long it was before I heard the War Requiem and was completely bowled over, firstly because I loved Britten’s music, and also because of Owen’s poems which I hadn’t really been exposed to before.

Before that one tended to get the Rupert Brooke angle on war which is jingoistic, unfelt and unmeaning. Even that can be thrown at other, greater war poets, but there something human, passionate and real about Owen’s words that just bowled me over. It was certainly his words that finally gave me the strength to become an active pacifist. I mean not necessarily to oppose all forms of direct confrontation, but to do it from a pacifist viewpoint, which means there probably are last resorts, but they’re probably ones that must remain last resorts.

Britten was a pacifist too, did the War Requiem prompt you to investigate his politics?

PR: It didn’t make me investigate, it was self-evident that everything he wrote was a passionate call for understanding, for compassion. Billy Budd and Peter Grimes [the heroes of two Britten Operas] are victims of misunderstanding on a personal level, and victims of cruelty and gross misunderstanding on a global level, like in the War Requiem. In fact I never read anything about Britten until quite recently, I read one of the biographies on him. I did do a portrait of him from photographs when I was at art school, which I sent to him but I didn’t hear anything back. I guess I was in love with him, and his music.

Do you see parallels between the two of you when it comes to your use of Owen’s poetry as a subject?

PR: I don’t want to big myself up or little myself down, but I think Britten and I had a very similar passion. He was a gay man and at that time it was not easy to be a gay man. I’m not gay, I don’t regard myself as genderised, but that softness introduced me to a certain softness that wasn’t particularly common in those days. Really it was that sense of supporting the outsider, supporting the wayward, the maverick, which I found so obviously attractive. It’s not that massively obvious in his work, but one sees it in all of his work. That said, to claim a deep affinity might be a bit pretentious of me.

The two of you have both set Owen’s poems to music, was it hard to detach yourself from Britten’s approach?

PR:I knew I couldn’t repeat the patterns or timing of Britten. I had to find new ways of looking at it, and as I’ve performed the work about eight times now, each time I’m able to get deeper into the resonances of the words themselves. I’m not hearing the music at all, I’m finding my own interpretations. As far as the music on my presentation goes, I decided from the very start that I was going to do it with [pianist] Liam Noble. I’ve worked with him and his interpretive skills and listening skills are massive. I knew he would pick up on the resonances, the emotional timbre, and it worked. Two days before the first performance in 2014, I bumped into [cellist] Kate Short, who I’ve often worked with. I told her about the project and she was so passionate about it, the War Requiem and Britten and Owen, so I invited her along.

Every performance is completely different, it’s a golden rule in progressive jazz that you don’t repeat yourself. Just because we manage to pull something off in what we all agree works really well, that doesn’t mean we’ll ever try to replicate it. I think the three of us are just finding deeper and deeper meanings and expressions within the words.

Why was progressive jazz the musical style with which you wanted to approach Owen’s words?

PR: Because I think it listens. I could have done arrangements and it would have taken a lot of time, but I think I wanted to go beyond the formal understanding of Owen and go deeper and deeper into the heart of what it was. Performing it is an unbelievably demanding thing to do, because it’s a long piece to do while trying to honour Owen, and it’s gruelling to talk about those horrors in such graphic form, and giving them even more graphic form because of the manner in which I approach it.

You can tell from the album that that manner is incredibly intense, you really get into character. Just how draining is it emotionally and physically to perform live?

PR: When I’m performing live, fighting back tears and fighting back explosions of real anger is unbelievably horrible. It’s not a nice piece to do! I recall the second time I performed it in a little village hall, built during the Second World War and incredibly atmospheric, with the funny smell that village halls have, it seemed much more real as a setting than a jazz club. Not long before that I’d had a heart attack and I was feeling very vulnerable. I didn’t know whether I’d even get through it. I actually, in my whole being, was in the trenches, crawling through the mud and blood and stink and noise. That was where I was coming from. It wasn’t imagined, it became a reality in the darkness on the badly lit stage.

There’s love in Owen’s poetry too, does that make its way into your interpretation?

PR: I certainly hope so. ‘I am the enemy you killed, my friend’, that’s one of the hardest lines, it’s the one that hit me as a kid where I suddenly understood I didn’t need to follow the line my father gave me that ‘All Huns are bastards’. There’s almost a homoerotic quality to some of Owen’s descriptions, I hope I never overplay any of those things but I’m very conscious of them, I can see the character he’s talking about, I can feel them, and the love that gave rise to those poems. It goes beyond simple observation to something much more ancient that comes through Daoism, that there is no seperateness, that we are one common being. I think that’s very profound in his work. There’s never blame, there’s only in a strange way something beyond and above the horror he describes, something that’s magnificent and untouched and beautiful. Again, I hope that’s captured in some way. I think it was captured in the War Requiem. Some of Britten’s settings are just transcendent at capturing that ambiguity.

Why’s it so important for you to put yourself through such a demanding experience?

PR: For the same reason Owen wrote his poems: because it matters. It was something I thought I’d like to do a good few years ago, earlier this century, and I’d thought of asking Liam to do it. I’d never really gotten round to doing anything about it, and then when the centenary of the war came round I thought ‘I’ve got to do it’. I was really worried there was going to be a horrible degree of jingoism and nationalism rising, which in a less direct way has risen, and I wanted to present a counterpoint. I vowed that from 2014 to 2018 I’d perform it as often as I could, wherever I could, which is what I’ve done. I’m doing it because it’s important, because anything that can promote or open up the cause of peace and love, I’ll do. I’ll do it to death’s bed, because it matters. That’s almost become the standard by which I operate now. I do a hell of a lot of work, but the one condition I have isn’t money, time or demand, it’s whether I can represent the cause of peace and love.

What Passing Bells is released via One Little Indian on November 3.