The theme for the third and final installation of Tate Britain’s ‘Late At Tate’ series is ‘Transform’, and the curators for the evenings have a particular fascination with that concept. Placing an onus on modern art and culture, they’re hoping to develop the image of the Tate Britain in the eyes of Britain’s youth. It’s about not being "that curmudgeonly place in Pimlico that’s packed with Turner" and instead opening their doors late and trying to fill those ornate halls with a new brand of current, dynamic work.

The perfect embodiment for the adage of reimagining an old archaic space with contemporary vision would be this work of an architect, sound designer and an illustrator. Operating out of Paris is Nonotak – Noemi Schipfer and Takami Nakamoto – a duo who are obsessed by flattening ‘pretension’ and democratising the language of art through their spontaneous and kinetic use of light, audio and visuals.

Tell us about Nonotak and the concept for your ‘Late At Tate’ Piece

Takami Nakamoto: Nonotak are a creative studio that works around performances and art pieces, but also visual installations. With this project for Tate, we wanted to show the two aspects of our work: performance and installations, but all in the same evening. The idea is to have this installation running as a loop throughout the evening, but at some point we kind of, plug our computers into it and we do a live set.

So when you aren’t plugged into the installation, does the loop have any autonomy? Can it operate of its own accord? Or is it just a loop?

TN: We change the set up technically. So for the installation we use a sequence that is a loop and we use only one program, but for the live aspect of the night we’re using a program called ‘MadMapper’. Some awesome guys called GarageCUBE and the people from 1024 make it. It allows you to VJ, which is essentially DJing visuals, but it allows us to convert pixel information into light information. So, it allows us to easily get into a live aspect, even if we’re using lights.

You have a communicative style, but with an absence of literal language, is there anything you’re trying to say with this piece? Are you trying to make a grander statement?

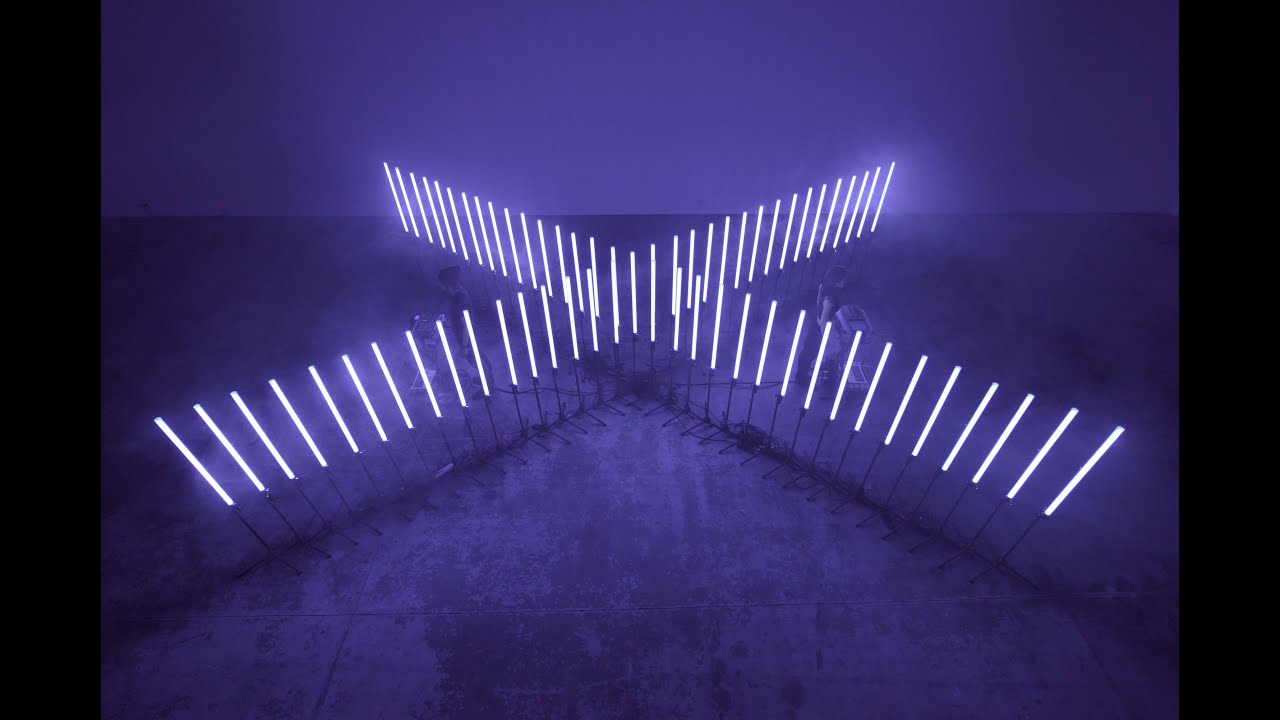

TN: It’s part of our series of experimentation around the notion of space, light and sound, and the relationship between them. As you can see, our installations are quite – not similar – but they all speak the same language. When it comes to projection, we like to use it as lights: (in this instance), I think using this X and Y-axis allows us to play with the shadows and specialise the lights, and the setup allows people to walk around it. So we found it was interesting to have an installation and performance that had no front. In this way, putting this installation at Tate is fantastic, because people can enjoy the sound and the lights going on in this space and it’s all super related to the context itself.

How so?

TN: We’re going to turn off all the lights, and it’s going to affect the whole space. We decided to put it at the back end of the Tate Britain space, which is awesome, the ceiling will have crazy shadows and stuff. I think it does make sense to do it here because the concept was all about playing with the silhouettes of the audience and playing with the perception of the space.

It’s interesting that you’ve said that. In the past with your shows like Parallels, you’ve created a virtual space for people to immerse themselves in, but did having this kind of old, archaic, historic space make you think about the project in a slightly different way?

TN: I think that it just adds so much excitement to the project. For instance, a project like Parallels creates a virtual space, so it’s good for spaces that aren’t as unique because it transforms it, and you don’t see what’s around anymore. But for this project we went for a light project, because it can affect the context you’re putting it in. As it’s pure light, it’s going to offset everywhere and the way it’s going to diffuse itself is very much different to projections that are aimed to a particular surface. So for this project, it’s inspiring to get this kind of space and, also, this kind of sounding space. There’s so much echo in this space, we’ve turned off all types of reverb and effects we had in the sound production. We can just use the natural reverb of the space.

Things like that are really interesting: everything we think about production-wise, in one show, has become totally different. It’s going to force us to change our setup, and it’s going to sound different. I think it’s important to have this unique relationship to every show, so it’s inspiring to have this space.

Have you been able to prepare for those surprises? Have you tried anything out yet?

TN: I visited the space last week. So I think we have an idea of how it’s going to sound, but you never know, so it’s part of the excitement.

As an architect, what kind of impact does structure and environment have on the sound design have on the sound design and musical side of Nonotak?

TN: A lot of things. For instance, the fact we’re a duo – we don’t work with anyone – and we can do sound and visuals at the same time is quite a freedom, a big strength. But we don’t disassociate visuals and sound. And with me being a producer, we can also change how the sound design was made in a matter of seconds. So if we need to create more of a focus on the visuals or sometimes to the sound, we have that flexibility that not many artists have access to. In terms of sound design, because I played in a metal/hardcore band before Nonotak, I have a musician-type relationship with sound in general. So beginning to work in sound design after working in a band makes you realise that you have so many feels that you didn’t explore. And the relationship between space and sound is something I’ve always been fascinated by. Sound is an element that gives information about a special environment. So making visuals that are specialised with sound that are synchronised to it gives you freedom to move the audience where you want to move them. Immersing an audience is what we want to do.

Everything we do is about immersion, or something really simple: like a simple kind of relationship within the visualar and the art piece. Like, not putting a wall between us and them. They don’t need to understand the text or concept, they’re just fed by their senses. Then, after that, if they want to, they can read the context and have an idea about what we’re trying to say. But I’ve never been into the art scene, because I was more of a musician. This kind of art which is immersive is interesting as people who aren’t into art can touch somewhere in the heart of where art belongs. I feel like everyone likes art, but we don’t give them the right opportunity.

Maybe it eradicates some of that phantom elitism that surrounds the art world.

It’s so interesting to show some our work at the Tate Britain, because I always had that ‘elitist’ kind of vision of Tate, which is prestigious too. But it is pretty awesome.

How much of the performance will be spontaneous and unique to the evening? Is the music and sound design performed live?

TN: There will be a live set. It is audioreactive at points, so we pretty much connect two computers and two programs through WiFi, MIDI, whatever. You can communicate by sound, data – it’s always connected.

Do the lights react to frequencies? Notes?

TN: It can be notes, it can be frequencies – when we’re doing audioreactive stuff, you can just split the inputs through three different spectrums, you know: the high-end, medium-end, low-end. Then you can divide what the program is hearing, and what we can do is because we also do the music production side is, if we need a kick, we just get a kick track that only the other soundcard is listening to. Everytime you then get a clean signal from a click, you can gate stuff, trigger stuff. Also, you can modify the way they get triggered. So just in sound you can finetune the threshold, the gate, the velocity – stuff like that.

Is that related to things like the brightness in the lights?

TN: Yes. And because we’re using a VJ program in the live sense, it makes it easier to do that. Otherwise, it would be kind of data-based. But now, we can even do things like have the lights react to the visuals on a web cam.

So your lights can react to pixels?

TN: Yeah. So for this one, we’re using two-dimensional compositions that are black and white. Then we’ll VJ and convert that into lights, and we have that freedom to do what we want. Like audioreactive note-triggered stuff, we can change how things react on the fly, which is not that easy when it comes to light. It’s more like we’re VJing a night. A lot of VJ programs are trying to develop that kind of thing now.

People ask how we’re controlling everything, and have no idea that we’re dictating the music, lights and everything with visuals on a webcam and we can change it on the fly.

So Noemi, you’re an illustrator, so maybe you have a more classical connection to art?

Noemi Schipfer: Yeah, I was working with 2D static images, but Takami gave me the dimension and the notion of space because of his background in architecture. Now, even if we use visuals in our installations, we don’t consider them to be visuals but more like night. So we have a different kind of approach.

TN: I think what is important, for me, is that all of the visual aspects of Nonotak are based on kinetic art. A lot of lines, vibration, and repetition. And I think that it’s quite influenced by Noemi’s work, which is pretty much based on lines. She does really interesting books for kids, which are very interesting, because that work comes with a lot of constraints, but she still managed to get a very artistic amount of work out of it.

Decades ago, people may have expected maybe work of that ilk in the Tate Britain. How far from what people would expect in this setting do you feel you are?

TN: It’s a difficult question. We feel so far away from Tate. I’ve always been so fascinated by Tate, I’ve always felt like ‘this is art, this is prestigious’. So it’s more like we’ve been fascinated and intimidated, I don’t know. But one thing that we’re sure about is that we’re bringing something that is part of the digital art scene into a modern art museum. It’s really nice because, even the guys who are booking the event itself, they’re willing to bring another dimension to museums in general. I feel like they like the idea that some festivals are doing art pieces and mixing it with clubbing and musical creation. Things are changing slightly: you have music curators, festival curators, random guys with visionary ideas. Like Alain Mongeau with MUTEK: 15 years ago he decided that electronic music and art can be merged so well that it can become one thing. So we feel really lucky to be one of the first artists to bring this idea to the Tate. I know that half of the people coming will be used to the usual exhibitons, so it will be cool to have an audience from a different scene.

Do you ever have the temptation to create a product that you can sell?

TN: Yeah, it’s going to maybe happen in Taiwan. It’s weird, when people ask ‘do you sell pieces?’ I’m like ‘well, do you have a room that can be in total dark with projectors and sound blasting in? Do you have a museum?’ With an art piece, you live with it. Where as I don’t think you could live with our stuff. But I know there are a lot of new collectors which have whole houses devoted to buying installations, it’s weird we never thought about it, but since we’ve had proposals, we have.

Are they one-off installations for somebody?

TN: It’s a limited version of an installation we’ve been showing. But I think it’s going to be a limited version, but it will question the fact whether we can then redo that installation. But I think it’s fine, it does make sense.

If you were thinking about a commercial agenda, would it have an impact on the art you create?

TN: No, no. It’s all about the fun first. What’s the goal if not?

Do you think that this kind of commercial influence can be good for the way art is headed?

Money can always have a negative and postive impact at the same time. But I feel like, we like being in a weird place so long as what we make a living out of are things like festivals, which is pretty much commercial, we also like artists that tour. When it comes to selling pieces, so long as you aren’t selling them to brands that won’t respect your work or will dirty it… So long as we’re a creative studio – I mean, we don’t have the pretension to claim to be artists – we feel like we’re more of a creative studio that is fun. We do a lot of experimenting, so if one day if we get asked to do something commercial, we would do it if it is interesting in terms of its context. If we can make it fun, it will look different to other commercial things. We’ll never be blocked by context: we’ll find an idea that changes the game.

So would you say it’s more about the experience than the art itself?

TN: Yeah, I mean, all the contexts are just arguments for us to create. So that’s why we’re also doing performances, installations, art pieces that don’t use electricity. We’ve started to think about working for brands doing window displays in our kind of language. So we’re really open minded.

Nonotak perform in the evening at ‘Late At Tate’ this Friday 5th of June. The admission for the event is free.

<div class="fb-comments" data-href="http://thequietus.com/articles/17998-nonotak-late-at-tate-2015-preview-interview” data-width="550">