Every good tale begins with a dark and stormy night. And there are at least two storms brewing on the eve of the 13th installment of Mutek, Montréal’s eminent festival for electronic music and the digital arts. The first is a freak deluge of rain that temporarily closes the airport to incoming travelers, floods streets, gnarls traffic, and swells the walls of my old wooden shack in the St. Henri district of town; the second the nightly student demonstrations in protest of the provincial government’s proposed rise in tuition fees by over 70%. Known locally as the ‘manifencours’ and/or ‘casseroles’ (the former meaning ‘protest in progress,’ the latter in reference to the civilly disobedient practice of banging pots and pans during recent marches), the movement has now been underway in the city for nearly four months.

So there are, in fact, two music festivals coiling around each other in early June: one whose sounds are machine-made; the other soundtracked by a deliberately amorphous and jubilant crowd brandishing whistles, horns, hollers, and the acoustic percussion of kitchenware. Since the May 18th passage of an emergency provisional legislation called ‘Bill 78’ – an anti-demonstration law that subsequently drew criticism from the UN and Amnesty International – protesters have increasingly been heard chanting: "La loi spéciale / On s’en câlisse!" (Roughly translated: "We don’t give a fuck about the special law!") Concurrent rhetoric in the local media has focused on how the manif might threaten the tourist season, using lucrative events like the Canadian Grand Prix to bring awareness to the cause. But there was really no ideological hijacking necessary here: many out-of-towner attendees have arrived well-informed, and some are fairly keen to be involved, pinning the student movement’s symbolic red squares to their jackets and handbags. One could have quite literally marched to and from Mutek this year; to borrow a phrase from a friend, the demonstrations are a special kind of public transportation, in which one is actually transported by the public.

A slightly sketchy stretch of St. Laurent boulevard, between rue Sainte-Catherine and René Lévesque, is home to three main venues – the Monument-National theatre, the Société des arts technologiques (SAT), and Métropolis – which host Mutek’s larger, longer, and later A/Visions and Nocturne events. The nighttime line-ups are programmed against each other, so it’s common for lanyard-clad clans to travel between the sites, catching pieces of competing performances, passing by crumbling buildings, gritty bars, and the Café Cléopâtre – one of the last remaining traces of the lower main’s red light district. Workshops with artists, journalists, scholars, and industry representatives are held at Monument-National during the day, and in the afternoon, gourmet street food prepared by the SAT’s Foodlab is served up at Place de la paix – a shaded square park across the street – along with sets from local DJs. After dark, a carnivalesque energy takes over the quartier, amplified by oscillating electronic sounds and destabilizing bass heaving out from various nightclubs. People go and come, get their chits ripped, passes punched, and hands stamped; they stand outside, smoke and chat while shifty street vendors buy and sell tickets. Meanwhile, with their lights revolving into the distance, ubiquitous walls of police vehicles – and the echoes of casseroles protesters clanging forth ahead of them – add further depth to the scene.

Since you can’t possibly attend everything that Mutek has on offer, you must choose strategically, and I choose to drift slowly through the festival this year. (Last year, I learned my lesson after ingesting some cheap wizz with a perfect stranger, hoping it’d keep me going through Richie Hawtin’s after-hours set. Instead, I ended up with a nasty flu halfway through the festival, and for an entire week afterwards. Moral of the story: take only expensive drugs, in the company of imperfect friends.) On the 31st of May, I make a point to attend the Q&A session with Keith Fullerton Whitman, moderated by Wire magazine deputy editor Frances Morgan, who asks sharp questions and delivers acute commentary. Whitman speaks about his experiments with modular synthesis, attempting to electronically construct the controllably chaotic microfrequencies characteristic of acoustic instrumentation. He equates his process with beekeeping: directing the vibrant material circulation of electric signals, as smoke does with a swarm, but allowing for and embracing the few miscreants who eschew the hive. Morgan plays a selection of Whitman’s works, which reflect influences from his encyclopedic knowledge of early and undiscovered electronic music, but push into improvisatory terrains that emphasise indeterminate, performative elements in both form and texture. It’s a lively and refreshing discussion, which affords further depth, shape and contour to the animate sense of off-kilter geometry in Whitman’s music.

Review continues after picture.

Le Révélateur

Later the same evening, Shackleton performs at Métropolis, stealthily weaving in material from his recent Drawbar Organ EPs. He journeys seamlessly through an accomplished oeuvre of deep, descendent dubstep, punctuated by undulating rhythms and unsteady organic tonalities. The visual elements of the show are tastefully stark, and the sound accordingly sublime. There is an alcove, just to the left of the stage, where the bass almost levitates you off the floor: a friend of mine pointed it out to me during Amon Tobin’s set last year. Of course, I can’t help but share this with my companion tonight, as we linger in the same spot throughout Shackleton’s performance. Subterranean pulses of sound pressure seem to rearrange every molecule in our bodies. As Monolake takes the stage, however, those soft pulses become all the more visceral, and a tad menacing. The lowest frequencies form standing waves in the space of the auditorium, and we’re physically pushed backwards by an onslaught of flatulent, punishing bass. It’s hair-vibratingly loud, and the best parts of the performance are when the uncomfortable thumping gives way into more ambient territories. Seeking refuge, we ascend to the balcony, but there proves to be no bona fide escape until we ultimately leave the building. By this point I’ve missed the last metro, so walk home happily, giving my ears a chance to recalibrate.

The next afternoon, I attend the second Wire session with Morgan and A Guy Called Gerald (Simpson), who regales the audience with tales of yore, playing unreleased tracks from a hard drive so apparently mammoth that he can scarcely navigate through the sea of material. He discusses the connection between music and dance, lamenting producers who make music solely to be beat-matched, and DJs who neglect to adjust their sets to the movements of the crowd. Still, Simpson remains classy and positive throughout a lengthy Q&A session with the audience, and refers more than once to his recent True School’ manifesto – a call to "encourage inventiveness in a medium that has no boundaries." Interestingly, though, the tracks that Simpson chooses to play are themselves reinventions of a genre that hit its peak more than 15 years ago. Nonetheless, they’re quite good, and successfully invoke an aching reminiscence for a time when drum & bass was still contemporary.

Her Ghost – Steve Goodman, Ms. Haptic & MFO

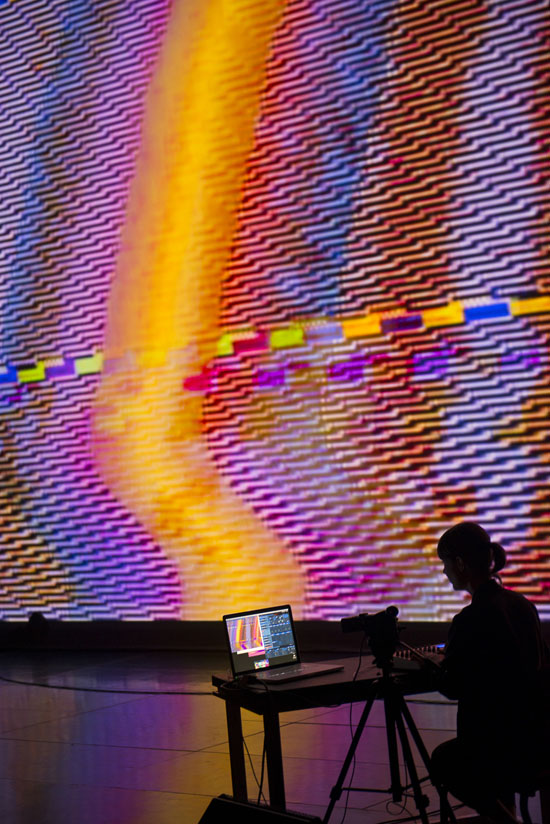

Later in the evening, we catch an expertly curated line-up at the lavish and historic Salle Ludger-Duvernay at Monument-National, a plush seated theatre built in the late 19th century. Local artists Le Révélateur (musician Roger Tellier-Craig and video artist Sabrina Ratté) open the set with rolling, arpeggiated synth tones accompanied by sunny analogue video feedback that, at times, resembles a psychedelic chess board folding in on itself – apt imagery for Tellier-Craig’s music-is-math aesthetic. The duo has quickly become one of the more interesting electronic acts emerging from Montréal’s fertile underground scene, and this performance lives up to their mounting reputation as important local artists.

The second presentation is entitled Her Ghost, a reinterpretation of Chris Marker’s La Jetée imagined by Kode9 (Steve Goodman), Ms. Haptic (Jessica Edwards), and the MFO collective (Marcel Weber and Lucy Benson). The images are taken from the original film, rephotographed, chopped and screwed, and set against Goodman’s guttural score, and Edwards’ live narration – a reworking of the script from the female protagonist’s perspective. Admittedly, I was a bit skeptical coming into the show, wondering how they would honor what many consider to be an already perfect film. But the sound, images, and voice flow flawlessly together, and the result is a triumphantly bleak performance piece that pays respectful homage to Marker’s nostalgic film, while twisting and mutating the original elements into something captivatingly advanced. Rounding out the evening is a set by Roly Porter [pictured at the top of this review], also paired up with stunning visuals created by the MFO collective. Porter’s crisp and angular sonic assault creeps up through the upholstery, mirrored by MFO’s skittering images of abstracted, rural dilapidation. We stumble out of the theatre requiring beverages, and recline on a downtown patio, watching straggling protesters and rows of police vans retire for the night.

I had very much wanted to make the third and final Wire session the next day, with the crew behind Her Ghost, but feel compelled to partake in the afternoon demonstration against Bill 78. Although it’s pouring with rain, a crowd of about 25,000 protesters take both directions of Avenue du Parc, and turn east on Mont-Royal, filling the street for several blocks and temporarily suspending traffic. Some honk in support, others out of impatience, and many restaurant and café workers stand outside their establishments banging pots and pans in consort with the procession. Billed as a family-friendly event, ages range from infants to grandparents, so the demonstration has a smaller police-and-pepper-spray presence than those I’ve participated in previously. And although they immediately declared the demonstration illegal (as they’ve been doing consistently since the odious law was passed), the cops keep their distance, and to the best of my knowledge, no arrests are made.

At twilight, we put on our Sunday best for the collaborative performance between Tim Hecker and Stephen O’Malley at the spectacular St. James United on rue Sainte-Catherine. The church has been recently refurbished, salvaging one of the city’s more dramatic pipe organ installations (which Hecker later defiles). I’ve been eagerly anticipating the experience, having never been privy to one of Hecker’s legendary organ recitals. The soirée is opened by another local duo, Les Momies de Palerme, whose eerily ethereal combination of synthesizer, violin, and female voice suit the solemn reverence of the space. The first quarter-hour of the Hecker/O’Malley set is transcendental, the two entwined in intricate, lattice-like harmonic structures. Unfortunately, the guitar ends up rather dominating, leaving insufficient space for Hecker to breath. I notice a few shuffling and restless audience members, trying to get comfortable in their pews. Some begin leaving. I’ve heard Hecker perform about a dozen times previously – nary an unremarkable happening – and wish at this point that it’s just been a solo show. We leave, a little bit saddened, but Les Momies’ creepy whimsy and the first 15 minutes of Hecker and O’Malley’s alliance were more than enough to have made attending worthwhile. We eat dinner and count cop cars, and eventually stagger back to Métropolis to hear A Guy Called Gerald, sinking comfortably into retrofuturistic ecstasy.

In Montréal, everything is built at a slight slant. There are no clean corners, alleyways veer off and realign unexpectedly, the pavement is fractured and jagged, buildings lean against one another, their crooked rooftops seemingly standing in mutual solidarity. There are uneven spaces between things here, producing both metaphorical and literal urban microfrequencies, to use an analogy from Whitman’s talk – something homologously shaped by both the metropolitan architecture, and its human inhabitants. I want to think that, regardless of its international performers, this culturally creative/accumulative city has everything to do with the avant-garde sound of Mutek, and vice versa. I recently wondered aloud to a friend of mine why the student associations didn’t obstruct the festival, as they’d promised to do with so many others here this summer. He replied: "Because Mutek isn’t evil." The manifencours anchor this lucky 13th year with vivacious bearings, and as the casseroles ring into the night, I bid adieu to my festival mates, and march home.

Photographs by Caroline Hayeur