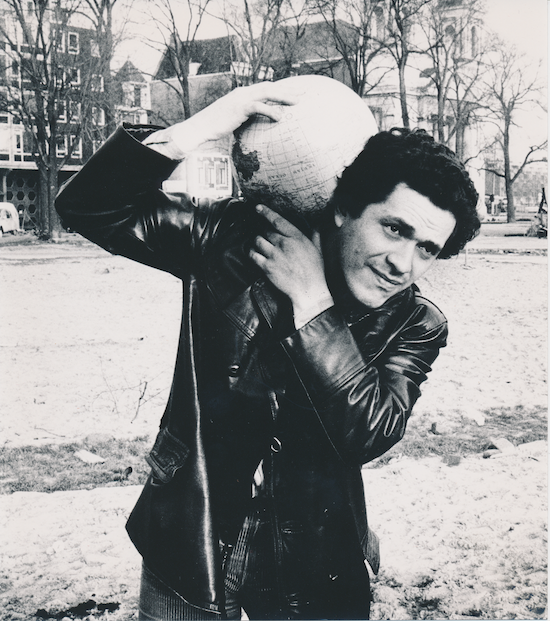

Michel Waisvisz. © The Michel Waisvisz Archive

At first glance, Touched By Sound is a tribute show like any other. Marking the life and work of the pioneering musician, performer and instrument-maker Michel Waisvisz, who died in 2008, the artist Tarek Atoui was given access to Wasvisz’s archives. Working in collaboration with Waisvisz’s former colleague and partner, the academic and engineer Kristina Andersen, they have put together a special day of programming as part of this year’s Sonic Acts Biennial in Amsterdam, consisting of workshops, talks and a closing concert, which takes place on March 3 at BIMHUIS.

So far, so straightforward. Dig deeper, however, and you’ll find that this is not a straightforward tribute show. There’s no freezing of Waisvisz’s life and work as an artefact, no attempt to canonise his legacy, no inertia. Rather, as Atoui and Andersen explain when tQ speaks to them via Zoom, it was a chance to embrace the immediacy and progressiveness that always defined Waisvisz’s work. He was an artist whose approach was daring and forward-thinking, largely improvisational and performance-based, and, therefore, Touched By Sound is too.

At the Studio For Electro Instrumental Music (STEIM), a research centre for the development of new musical instruments where he was artistic director, Waisvisz created and co-created such contraptions as the Cracklebox, a small box with metal contacts on top which makes unusual sounds when pressed by the performer’s fingers, their body becoming a part of the electronic circuit; and The Hands, one of the world’s first gestural MIDI controllers attached to the player’s palms. Approaching sound as something multi-sensory, that can be touched as much as heard, his performances were mischievous and unpredictable even to the artist himself.

"We didn’t want to think of it as just a freezing of his ideas or a scholarly work," says Andersen. "Rather, we’re saying, ‘How can we take that stuff that has a certain spirit, and use it in new forms, so it’s available to be questioned, played and engaged with?’ Otherwise we’d just be putting things into boxes, which would be completely meaningless." Working alongside other instrument-making artists, including Boris Shershenkov and Görkem Arıkan, and former STEIM engineers, as well as restored versions of Waisvisz’s original instruments, the event will feature entirely new creations, some of which were inspired by photographs of performances uncovered in Waisvisz’s archive. These will be demonstrated in a presentation by the artists discussing the process of building and re-editing them.

This will be followed by a performance, which will see Atoui, Arıkan and Shershenkov joined by Takuro Mizuta Lippit (AKA dj sniff), Ji Youn Kang and Julia Giertz. In addition, Atoui will be hosting workshops called Under Scores, working with different participants to engage with a variety of Waisvisz’s musical scores. Each of those scores demonstrates a different approach to music, from notes, drawings and diagrams, to software codes and instructions. Atoui also leads another workshop called Within, in collaboration with Kentalis, an organisation supporting those who are hearing-impaired, deaf or deaf-blind, which will further explore non-auditory approaches to sound and a focus on touch.

Touched By Sound takes place on March 3, 2024. Find more information here, and read tQ’s conversation with Atoui and Andersen about the event below.

Atoui and Andersen exploring Waisvisz’s archive. © Amie Galbraith

To those who are unaware, could you explain who Michel Waisvisz was, and why he’s such an important figure?

Kristina Andersen: He came out of a period in Holland where the boundaries between art and society and music were breaking down. This was something happening across Europe, there was lots of experimentation, but Michel was very much somebody who became a part of the Dutch ‘flavour’. We also have a lot of free jazz here, and a lot of what some people might call ‘composing the now’, the idea that composition is something to be done live. He came out of art and theatre communities that wanted to merge and play around with these formats, and as a person he was incredibly single-minded. He managed to keep doing this work over a lifetime. He became the director of STEIM, which was a small lab for experimental electronic music where Tarek was [later] artistic director, and where I worked for close to 15 years. We would invite people to come with their instrumental concerns, guests might want to build a new instrument, or work out new material, or do concerts and workshops. It was essentially a safe house where you could explore, and this was very much Michel’s doing. He created this environment where we always used to say that sound isolation goes in both directions. It’s not just saving your surroundings from the noise, but it’s also allowing you to step away from the world and try something that might be risky, or different from what you normally do.

Tarek Atoui: In my case, Michel was a friend and inspiration, and somebody I had the honour of meeting in the last few years of his life, when I was a resident at 26 or 27 years old. It was a privilege to be an artistic director at that early age, under his invitation. We shared a lot of common ideas about what electronic instruments are, and the role of the performer to adjust reality; the expressiveness of it. Sampling was also very relevant and interesting to both of us. He was my anchor to Holland too. After he passed away I actually left Europe to see other parts of the world.

Why is now the time to pay tribute to him, 16 years on from his death?

TA: As well as me being mature enough to pay homage to somebody who was that important to me, [16 years] was also the time I needed to be able to look back at his influence, now that I know a bit more about where I stand in my practice and in my art. Maybe it’s also because I’m a father, and I’ve started to think about what heritage is. What do we pass on and what do we leave behind? How can things be behind us and still speak to us today? That’s what has driven the project since we started to dig into Michel’s archives.

KA: I was married to Michel, and we have a daughter, so I had a double role in that sense. We worked together, but I’m also the caretaker of his archives. Part of my job is to consider whoever in the world might be interested, but in my mind I’m also caretaking the archives for our daughter. The other thing is that we’ve all had to figure out how to archive a practice that doesn’t lend itself to archiving. Michel was a performer, he was a maker of instruments and of games that were very much about the moment. We went through stages of trying to archive these things in the traditional sense, which was pointless and horrific and wrong. You have to make all the obvious mistakes first. Now we’re at the point where we’re saying, maybe we’re not here to freeze this information, maybe we are here to look at this ephemeral knowledge and reproduce it in other ephemeral forms. I think it took time for us to get there.

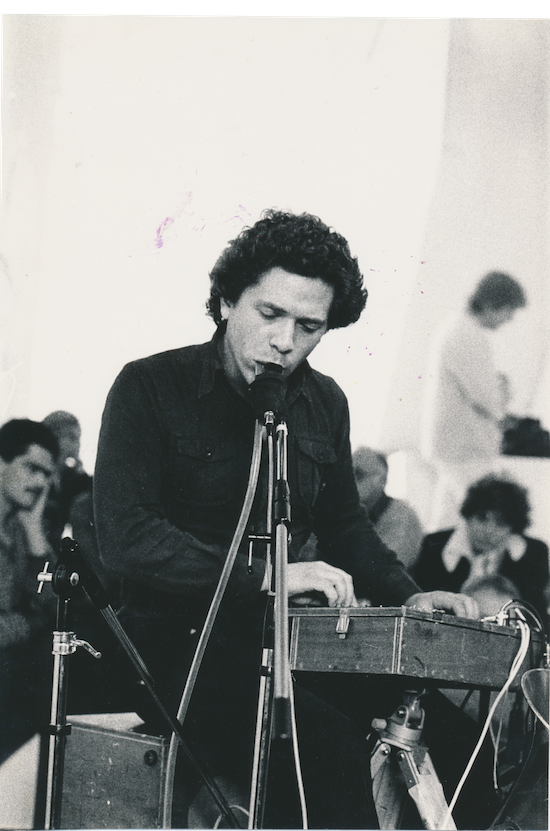

© The Michel Waisvisz Archive

What does the archive actually look like at this point?

KA: it looks like a room full of cardboard boxes, simply because a cardboard box seems to be the unifying medium for things to end up in. But within the cardboard boxes is an absolutely unholy mixture of things. There are drawings, electronics, maps, home built instruments and modified commercial instruments. There are recordings in every kind of media you can imagine.

TA: For me it was all ephemeral. Michel didn’t do any of this for it to be taken back by others, it was just responding to the moment, whether with improvisation in the studio or the moment of being on stage for a show, troubleshooting and building and soldering at the last minute. So [with the archive] you are in a world where you feel that you’re a bit of an intruder, because you’re opening doors that were not meant for you to open. Kristina told me that if Michel could see us doing this work, he would say, ‘Why?’

KA: It’s not that he would stop us, but I have a feeling he would be like, ‘Why don’t you go and do some concerts?’

Which you’re now doing, with the performance at Sonic Acts. How are you taking his philosophy with you into the show?

TA: Kristina did a lot of work revisiting, restoring and re-activating certain things we mapped out in the archive. Sometimes I took another path, taking photos of Michel’s performance on an instrument used for a one-off show, and asking someone to make another, or asking people who were regular visitors at STEIM to [revisit] certain techniques or experiences they had in their early career. There was a spirit of not just reading Michel’s work, but using it as productive. An archive from which it’s possible to get a lot of new ideas, not just to revive the past.

How much of the performance is going to be improvised?

TA: What’s not improvised is the musicians’ names. There’s a lot of improvisation, like one of the evenings we used to have at STEIM, where a lot of people would share the same stage. We will do some rehearsals in advance and structure different inputs for the instruments that we have built and rebuilt for the project.

Tarek Atoui. © Locus Athens

What can you tell us about those instruments?

TA: One came from an idea [sparked by] a performance Michel did in the late 1970s with reel tape. I asked a friend and longtime collaborator Boris Shershenkov to look at a photo [of that show] and try to imagine what was behind this mechanism. Can we think of something similar that plays with long rolls of tape? A second was done by a person who used to go to STEIM, Görkem Arıkan. He went to the BIMHUIS Sound Lab and came back with ideas of working with flex sensors to create a dynamic frame, a work that you live in like a spider web. Boris’ instrument requires more practicing and virtuosity, but Görkem’s is much more open to the public.

KA: From my side, we’re recreating some of the older instruments. One of Michel’s synths was at the point of being unplayable because it was getting quite fragile – it took quite a beating in its time – so we remade one, just to give us the tools to actually play it. With some of the speaker boxes we did the same thing – figured out what they originally had been and made some copies. The idea is that over time, after Sonic Acts, we will be using these devices as starting points for making entirely new things.

Given the project’s forward-thinking nature, do you view it as having a future beyond Sonic Acts?

TA: I have in my notebook six chapters of things I would like to do with Michel’s work. At Sonic Acts we’re doing one chapter. A museum exhibition about Michel is not the way to go, but experiences like Sonic Acts, where we produce pieces, produce instruments, learn something out of organised workshops, this allows us to tackle chapter two.

© Amie Galbraith

STEIM no longer exists as an institution having closed in 2020 after cuts in the national funding system. Does this project feels like a continuation of its ethos?

KA: STEIM doesn’t exist any more, but it is there as almost a conceptual place that all of us are able to enter.

TA: And thanks to Kristina, parts of the STEIM family were gathered again in recreating instruments.

KA: All my renovations of instruments are being done with the original STEIM engineers, so I’m bringing a bunch of people out of retirement with the promise of lunch. When we re-opened one of the speaker boxes, we could immediately say ‘So and so made that, that’s their solder joint! They never used the proper range of wiring.’ We were talking about how every time you make a solder joint, you have to pull on it after, because that’s the STEIM test. I remember when I first came there, and one of the technicians came over and started jerking out all my solder joints. I remember being like, ‘Why would you do that?’ and they said that STEIM is building instruments that we’re going to use, and we never fail.

Touched By Sound takes place on 3 March at BIMHUIS in Amsterdam. For more information and tickets, click here.

It is part of Sonic Acts Biennial 2024: The Spell Of The Sensuous, which includes more than 50 events across 15 locations in the Dutch capital and takes place until 24 March. For the full line-up and further details, click here.