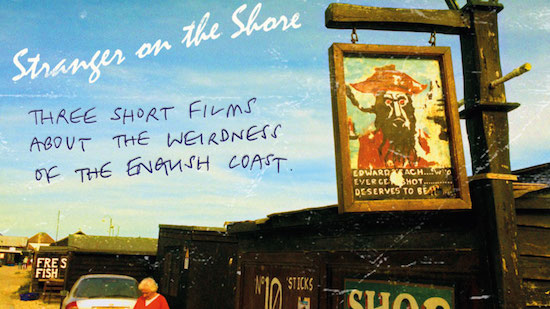

The novelist and broadcaster Michael Smith has again joined forces with the filmmaker Maxy Bianco to make three new short films, a cycle of video-poems exploring the weirdness of the English coast.

Smith and Bianco visited three locations to make the films – Hastings, the Essex Estuary and Whitby – and the resulting films are as beautiful, strange and singular as the places they depict, with Smith’s poetic prose imbuing them with a dark and doomed romance.

The films have been scored by Andrew Weatherall and Nina Walsh, with saxophone from the French composer Etmo. Smith has collaborated with Weatherall before, when the veteran acid house DJ provided a musical accompaniment to his last novel, Unreal City, a union that came about when Weatherall was the artist in resident at Faber, Smith’s publisher.

The films are being screened at the BFI as part of Sonic Cinema on May 31, with a live score from Weatherall and Walsh featuring alongside the screening. You can purchase tickets for the screening from the BFI here.

Ahead of the event, Smith spoke to The Quietus to reveal the inspiration behind the films, his move to St Leonards-on-Sea, how Brexit could affect Britain’s seaside resorts, and how he got the funding to make the films.

What was the inspiration for this cycle of films?

Michael Smith: I grew up by the sea and it’s sort of always in the blood, and in the imagination. I had a few places that I wanted to write about or film for a long time, but they were just short ideas, separate fragments. One day I had the thought, ‘the coast is weird’ and realised they could all fit into a bigger whole, and then these fragments joined up in a little flurry in my mind.

How did you decide on the locations for the films?

MS: The singularity and strangeness of their atmospheres. That’s always the fertile ground these kind of projects grow out of for me. I had a longer list of places, but the three I chose – Hastings, Whitby, Essex Estuary – were the ones that resonated most on some mysterious gut level.

What is it in particular that fascinates you about the towns and people of the English coast?

MS: The way they are in both a physical and metaphysical sense living on the margins, the edges of the country, the place where our culture meets something much bigger and more mysterious. This threshold quality just imbues it all with a sense of mystery, poetry and romance.

Stranger On The Shore (Trailer 1) from Maxy Neil Bianco on Vimeo.

You have fully immersed yourself in this world by moving to St Leonards-on-Sea, the "archetypal faded seaside town". What drew you there in particular and how have found it since you made the town your home?

MS: We moved because of me researching the place for the films actually! It just wove its magic spell on me. It was like a breath of fresh air, a second chance after London just got grindingly over expensive and impossible to keep afloat in. It’s got its grotty, dodgy side, but that’s kind of how I like it, as this means the creatives and eccentrics can afford it. When the sun gets low it looks impossibly pretty.

Post-Brexit, how do you see these places changing? Do you think tourists will come back to British resorts if travelling to Europe becomes more expensive?

MS: It was really interesting timing, because we were just finishing the films when the massive shock of the referendum came and suddenly the films took on a new emphasis. There is a David Shrigley cartoon that says: “GOOD LUCK IN THAT STRANGE AND BRUTAL KINGDOM YOU CALL HOME.” I became morbidly obsessed with it around the time. Suddenly all the St George crosses in the ropier pubs of St Leonards acquired an added menace. There’s a kind of totemic patriotism about the English seaside that’s bordering on the xenophobic, especially when these places are poor, like here, and that all came bubbling over a bit last summer. However, the diaspora of displaced metropolitan creatives has found a growing enclave here, and all this annoying media noise about the seaside becoming trendy again unfortunately means the second mortgagers are Air BnBing the shit out of it. Brexit has helped to polarise an already precarious balance of the cosmopolitan and the parochial.

What do you think is it about Andrew Weatherall and Nina Walsh’s music that particularly fits the mood of your films?

MS: It must have a lot to do with their skills, sensitivity and experience as musicians and producers. I’d like to think it’s also because we’re singing from the same hymn sheet. Whenever I work with them it just seems to fall together really effortlessly.

In the past you’ve made programmes for the BBC and written novels Faber – this time you had no backing from any outside sources. How did you go about funding the project and making the films?

MS: I was very lucky having the backing of BBC Four on earlier projects but this one was a real cottage industry effort where we just decided to get on with it. As with the handful of independent films I’ve made, they were very challenging logistically and financially, at points very frustrating, but also incredibly satisfying to make because of their complete artistic freedom. A film for any Broadcasting Corporation, British or otherwise, will always be a creative compromise. In any case, I don’t think they would have been interested or willing to commission these films, they’re too leftfield for their tastes.

The kind of films I like making are doable on a shoestring these days because the technology’s accessible, and it’s very liberating to work this way, according to your original vision of what the films should be with no other concerns or editorial pressures. I prefer the DIY approach, the old indie spirit – you get to do exactly what you want that way.

Saying that, it would have been impossible to complete the project without the modest Arts Council grant we applied for. In an era when creatives have effectively become free content providers, they’re one of the last bastions keeping England’s cultural life afloat. We got some very useful help and advice from Northern Film & Media, and also the Estuary Festival in Essex, who gave us a big spooky mansion to stay in while we filmed; our good pals over at Caught by the River/The Social have been as supportive as ever, helping give us a platform to get it out there, and the BFI likewise, so we’ve relied on quite a bit of support over the course of the project.

What’s next?

MS: Presuming those evil bastard Tories stay in power, I really want to make a longer film about the darkness that’s engulfing and poisoning the country at the moment, a kind of Brexit road movie. Again, that Shrigley postcard (“GOOD LUCK IN THAT STRANGE AND BRUTAL KINGDOM YOU CALL HOME”) keeps popping into my mind. If, by the grace of God, they don’t get back in, I’ll have to think of something else.