Two viewing postures: the first, upright, in a brightened gallery, the second, reclined, in a darkened screening room. How does the surrounding setting affect how we watch? The first LUX/ICA Biennial of Moving Images takes artists’ films out of the gallery, the archive, or the hard drive, and into the cinema.

One of the panel discussions, ‘Cinema as Art’, raised this question of physical context, and framed the biennial in terms of the boundaries between cinema, moving image and art. What happens when the cinema becomes not only the site of viewing, but of display? How does material place influence our engagement with moving image? If in the gallery, there is always another adjacent work to see, the cocoon-like black of the cinema may promote too much comfort for an active viewing experience. Now, there’s another frame within which viewers meet moving image – that of the laptop, screen glow reflected onto a too-close face. The distribution of artists’ moving image online brings a certain amount of accessibility, but the internet acts as a transient screening room, with skip forward controls and the temptation of new tabs.

The LUX/ICA Biennial launched then a two-pronged prerogative: to show a selection of often hard to find shorts, and to seek out an active engagement from viewers. While some of the works on the programme have been digitised, many remain on that format long precious to artists, 16mm film. The programmes of the biennial, curated by film enthusiasts, artists and writers from London and beyond, demand our undivided attention. For just as we slip into the shots of one filmmaker’s oeuvre, we are presented with another, often juxtapository film style. Curatorial themes poetically touch the necessary bases: places, politics, psychology, bodies, objects, technology. At times, the transition from one film to another is smooth, or seductively contrary; at others, the rhythm of passage from one artist’s work to the next is jolted and uncomfortable, like a misguided track on a mixtape.

The biennial coincided with the final weeks of the ICA exhibition, ‘Remote Control’, which explores the influence of television on contemporary culture, and marks the precedence of digital over analogue technology. The festival opened with a reincarnation of Mark Webber’s 1990s film club, Little Stabs At Happiness, named after the cult 1963 film by Ken Jacobs. Aside from the subsequent screenings there were evening performances, marrying theatrics with serial drama, live soundtracks with bodily response. There was also a synchronous Artists’ School, plus a documenting Live Journal. Here are some selected discoveries…

‘We only dream of places and resistance, for now’, curated by Carmen Billows

This programme, selected from an open call, looked at how bodies can offer resistance within socio-political spaces. Cyprien Gaillard’s Cities Of Gold And Other Mirrors (2009) stalks ravers on electronic highs in modernist buildings, then lingers within those buildings long after the people have gone. Gaillard’s setting is Cancún – the Benidorm of South America – where ’70s architecture, which forms the focus of most frames, outlasts the hedonistic parties that ravage it. Emptied of bodies, the resorts are left to host swimming dolphins and crawling vines; they are sites that become idyllic only after the tourists have gone. Finally, a glass building collapses, a slow motion implosion of culture.

The images of Hannes Schüpbach’s Falten (Folds, 2009) are meanwhile imprinted on my mind. Like a visual ode to the Baroque, Folds is a choreographed symphony of overlaps between material and movement, surface and skin. The camera performs pirouettes around fingertips and porcelain sculpture, flesh turning to marble and tracing paper to stone. Schüpbach orchestrates a montage of gestural arabesques, to provide a mesmerizing view onto the curves of the world.

‘Friends with Benefits’, curated by Ben Rivers

Ben Rivers curated the programme, ‘Friends with Benefits’, whose title, he claims: "refers neither to the Justin Timberlake sex friend movie, nor to people on the dole – though both these themes may have crossed over into this selection of films." ‘Friends with Benefits’ reflects certain of Rivers’ own concerns and constraints in filmmaking: to represent human relations, and, frequently, to have to do so on a limited budget. "Please will you come to the woods with eight other people, take off your clothes and cover yourself in mud and paint?" he jokes in his accompanying text, a reference to the making of his series, Slow Action (2010).

Rivers thus chooses the works of filmmakers who use their surrounding loved ones as subjects, for a warm hour and a half of intimate encounters. Ron Rice’s Senseless (1962) skirts between grainy, black and white shots of bull fighting and lovers’ entangled hair during a heady Mexican summer. Carnivorous and carnal, it is the antithesis of its title – a sensual celebration of the harvesting of crops, the carving of raw meat, and copulating bodies. Robert Nelson’s Deep Westurn (1974) shows a line of middle-aged male friends repetitively falling off chairs backwards at varying speeds (you had to be there), until the chairs become gravestones. It’s in memory of a friend. Laida Lertxundi’s Footnotes To A House Of Love (2007) occupies a couple’s relationship in an isolated house in the Californian desert, creating soft brushstrokes of sun and shadow. The couple’s cello and The Shangri-Las’ ‘Remember (Walking in the Sand)’ provide the soundtrack.

‘Inner Cinema: Films by Eric Duvivier’, curated by Yann Chateigné Tytelman

Surely the rarest find of the biennial, the films of Eric Duvivier study the most obscure reaches of the mind, inspired by Henri Michaux’s "l’espace du dedans" ("inner space"). ‘Inner Cinema’ was sourced by Swiss curator, Yann Chateigné Tytelman, from the archives of Sandoz Pharmaceutical, where Duvivier was commissioned over the course of several years to produce medical films. Out of over 600 productions meant to educate students on states of mental illness, Duvivier managed to make a handful of absurdist wonders.

Duvivier was the nephew of a Surrealist – and it shows. In Concerto méchanique pour la folie (Mechanical Concerto For Madness, 1963), for example, a female and a male in cream and black onesies approach a giant, Dali-esque telephone, before running through an assault course of pipes and zombies made out of speakers. Autoportrait d’un schizophrène (1977), which supposedly documents the mental state of schizophrenia, in fact plays out a moment of drugged delusion – the terrified realisation of one’s own reflection in a mirror, or the spiralling paths of an inward-turned mind.

Close to the ’70s French avant-garde (he also collaborated with Henri-Georges Clouzot), Duvivier references art of the period, including Gordon Matta-Clark’s Conical Intersect. You can watch Duvivier’s adaptation of Max Ernst’s collage novel, La femme 100 têtes, on Ubuweb.

‘Nine Films by Luther Price’, curated by Thomas Beard and Ed Halter

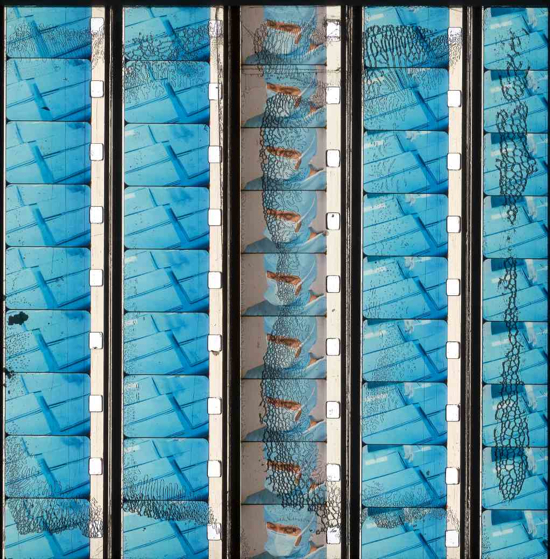

Luther Price engages with the physicality of film, though not out of preciousness or nostalgia. Rather, Price has a sculptor’s relationship with the medium – indeed, he previously trained in this craft. The curators of Light Industry in New York, Thomas Beard and Ed Halter, who also screened Price’s work at the Whitney earlier this year, described his meticulous ways of reworking old film stock. Collecting and appropriating found footage, from ethnographic documentary to home video and porn, Price carves, cuts and overpaints film strips on a light box. While the work of Price’s hand is at times intricate, at others it is crudely visceral, as much about effacing images as producing them.

The visual results of Price’s techniques range from the kaleidoscopic, as with his Inkblot series (2007), which involved painting and scratching off layers of colour, to the formally filmic – for A Patch Of Green (2004/2005), he placed pieces of 8mm film within a 16mm leader, so that scenes appear naively within a negative border. For his After The Garden series (2007), Price buried films in his garden until they decomposed in the soil, willing the aesthetic effects of decay. Played back on the projector, his reels often leave behind shards of their disintegration.

Handmade slide from Meat (1999), courtesy of Luther Price

For traditionalists, then, Price’s executions represent filmic abuse – a sentiment that is carried through to the experience of the viewer, who is at turns sonically and visually bludgeoned by flashing abstraction and white noise. Price’s films provide a physical exploration of form and matter, and how form might then fuse with feeling. Unlike the work of Stan Brakhage or the Structural-Materialists, there is an emotional import to the artist’s work, as he pushes the viewer to feel, be this in positive or negative ways. Curators speak of an "ecstatic violence" in the work of Price; there is a kind of orgasmic throb to the images as they pulse in and out of focus, coupled with the staccato assault of exposed sprocket holes as the filmstrip passes through the projector.

Price is anti-preservation. He wants his films to play out until they play no more, and it is worth any opportunity to experience them before they fade. Ed Halter expresses the artist’s ethos as such: "Film is only going to die once: we might as well enjoy it."

The LUX/ICA Biennial feels far from a celebration of film’s death. The spectrum of formats seen in the programme does, however, seem to mark a period of piqued awareness of the material and technology through which moving image arrives on the screen, be this analogue or digital.