In the 1960s and 70s, Hebden Bridge – the small Yorkshire town at the top of the steep Calder Valley between Leeds and Manchester – attracted scores of writers, artists and musicians looking for cheap living and studio spaces in the stone terraces and mill buildings which once supported a thriving set of industries. As documented by Martin Parr’s 1970s photographs of the town, collected in The Non-Conformists, this was a time of transition, when old traditions and practices – films at the oil-lit Picturehouse, congregations in hillside Methodist chapels, independent coal mines run by a handful of men – were dwindling. In their place, Hebden has evolved into a slightly mixed-up place: a liberal bubble of a town selling a Sunday supplement spectacle of rural bohemia – all handmade soaps, dog cafes and overpriced organic veg shops – whilst a still-rich vein of genuine creativity and alternative culture sits at the fringes of things.

Tucked down a side street in the town centre, between the post office and the canal, is The Trades Club. Built in 1923 by a group of the town’s trade unions, The Trades – sprung floor and all – had a successful few decades in providing a space for local revelry, before falling into disrepair with the decline of industry. In 1982 a committee was formed to bring life back to the building, and now The Trades has a name as one of the best small venues in the UK (thanks in no small part to Mal, the booker), bringing the likes of Patti Smith, Julian Cope, The Fall and Andrew Weatherall to this small ballroom stage.

And on a Thursday night in Hebden in midwinter, where the heavy snow on the tops has been reduced to slush in the town’s narrow streets, Heavenly Recordings host the first of a four-night residency at the Trades, bringing the majority of their roster up north to celebrate the label’s 25th anniversary. The walls of the Trades’ band room whirl with oil-like projections like the reflections of a lava lamp filled with fizzing lager. On the bar, the Bridestones brewery – based up the hill close to the gritstone outcrops from which it takes its name – has brewed a Heavenly bitter for the occasion. The tight wound corridor and snug working man’s club bar slowly fill with a diverse bunch of people: teenagers channelling Lou Reed and Grace Slick; the older crowd seemingly a mix of the curious and the seen-it-all, all Breton tops and Barbour coats.

And in the midst of it all, Heavenly’s founder Jeff Barrett, full of exuberance. I ask Jeff, "Why Hebden?"

"This time last year Jimi Goodwin played at the Trades Club, and I came up from London to see the show. As the train doors opened at Hebden station, a lad in front of me said to his mate "you can tell you’re in Hebden by the smell of the ganj". And I thought "right!" But walking from the station to the Trades, what I could actually smell were the chimneys, the wet air, the cobblestones. And in the few hundred yards to the venue, you cross two waterways – the canal and the river – to The Trades itself, which is a brilliant venue, and properly run. When we were planning the 25th anniversary weekend, it seemed to make sense to come back."

Tonight we were due a bill of Temples and The Wytches, but due to their guitarist having an (slightly bizarre, Spinal Tap-esque) accident with a chisel whilst building a pedal board, Temples have not made the trip. As Jeff recounts, the phonecall from Temples to let him know came at a tricky time "we were in our hire car, trying to get up the steep, snowy hillside roads to where we were staying. At one point we took a wrong turn, lost control and ended up in a snow drift. A tractor was pulling us out when I got the call: I said "let me call you back…" "

With 24 hours notice, Irish-Brazilian-Norwegian trio All We Are make the short trip from Liverpool to open the weekend. After a couple of – understandable – false starts, their clipped, minimal funk is a little lost in the room, with the edges and nuances of the band’s records rolled off. It works better when they ramp things up a bit, with widescreen processed guitar, clever stuttering beats and Guro Gikling’s taut basslines and heavenly vocals lending a feel of Julianna Barwick fronting The New Power Generation.

Before long, The Wytches are on stage, in a whirr of flailing headstocks and hair, with songs led by Love Buzz-saw guitar in lysergic smears of vaguely Eastern scales, frayed at the edges by stormy feedback and delay, and pulled back from the brink by a tight rhythm section. This is a band who have clearly been touring – there’s a practiced method in their chaotic whorls, not contrived, but carried along on a set of shared glances, nods and off-mic chants. It’s a hoot to watch, and the young crowd begin to get suitably rowdy, which – in an echo of Temples’ pedal board accident 24 hours earlier – leads to an early end to the set, as a pint of beer ends up all over plug sockets and pedals on stage, shorting the power and shortening the fun.

Friday night and the snow has stopped, replaced by a cold, stinging rain that whips through the streets. Inside The Trades bar, it’s standing room only, with raindrops evaporating off camel coats and Goretex hoods whilst plates of Thai food are passed carefully over the crowd to a group of lads playing pool in the corner, all watched over by faded photographs of union men on the wall.

The Voyeurs take to the stage as blue Viewmaster-like projections slowly turn above their heads. Dressed almost entirely in black, they have a loose, easy confidence on stage, hurtling through a set that refracts Faust’s ragged kosmiche repetition and British 70s glam beat through a Britpop lens. Charlie Boyer sings "rhubarb rhubarb" – the phrase is a theatrical device used to crate background dialogue on stage and on the TV – in a Verlaine-like yelp over a slow Velvets strut, as the bassist runs out of fretboard for his high melody lines and the zen-like guitarist repeats two grumbling notes like a mantra. Ending on ‘England Sings Rhubarb Rhubarb’, the mood is jubilant, as twinkling keys and time signature shifts evoke Suede playing ‘Joy Of A Toy’, and the crowd – now filling the room – show their appreciation.

Whilst there’s some shared aesthetic between The Voyeurs and Toy – the headliner’s opening song sounding like a motorik ‘Common People’ – Toy flout the openers’ sense of pop structure, as their extended psych-outs – made up of slowly-opening squalls of wah-ed guitar, metronomic drums with the kick mixed high, and tritone pulses of synthesiser – take on a real ferocity and force in this small room. Frontman Tom Dougall’s voice sits softly somewhere in the middle of it all, washed out by waves of echo, as the band sing laconic "aahhs" in backing. The juddering rhythm and distorted bass on ‘Fall Out Of Love’ rumble the sprung floor as rainbow light refracts over the stage and stars flicker off a mirror ball.

After a mid-set lull, where it seems the band are in need of a new idea or two, Toy end with ‘Join The Dots’, the Oscillations-like intro morphing into a long, celebratory repetition, repetition, repetition of charging rhythm and feedback, as blokes climb tables at the side of the room, arms aloft and bathing in the overwhelming volume. As the band exit stage left, the DJ starts up with Barrington Levy and Missy Elliott, the weight of the bass an apt continuation of what went before, as the crowd filters out to the bar and the glistening streets, and groups of local teenagers quietly slip in past the absent doorman, wide-eyed about it all.

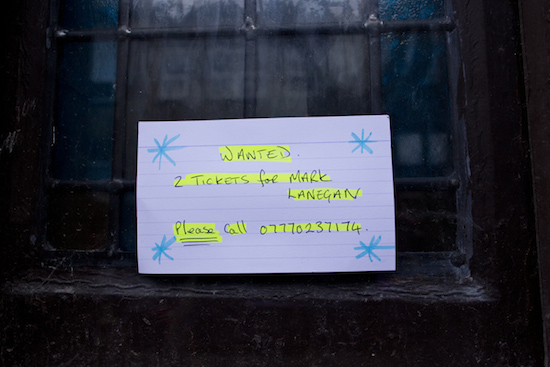

The air is heavy, cold and close on Saturday afternoon, as groups of shoppers slowly potter around town. In The Little Theatre, round the back of The Trades, Mark Lanegan is in conversation with journalist John Robb. Whether in nervousness or anticipation, Robb rocks on the front legs of his chair towards his interviewee, who talks slow and low, and is by turns wry and witty, particularly seeming to take pleasure in repeatedly teasing out the Anglo-American syllables of "dickhead" for comedic effect, in a way oddly reminiscent of Vic and Bob’s DI Fowler.

Lanegan’s wide-ranging and often self-deprecating chat takes in his childhood (in the Washington state ‘desert’, inland from the more commonly known tracts of misty forest); the beginnings of Screaming Trees (joined as a drummer with half a drum kit traded for a bag of weed; quickly migrated to vocals); his friendship with Josh Homme ("we go out to eat, to the movies, and occasionally record a song"); his numerous collaborations ("I say yes to things; my ex-wife called me the Michael Caine of rock"); and writing lyrics for his solo albums ("songs are pieces of dreams, sometimes the real meaning of a line reveals itself to me as I’m singing it on stage, and I get knocked off my stride").

As basslines wander over from the soundcheck next door, punctured by the crash of last night’s recycling being put out, things draw to a close in The Little Theatre with Lanegan talking about his love of Johnny Cash, "Every song I’ve written, there’s a piece of him in there: a man that could not have been nicer. And, maybe sometimes, I guess I could be nicer." On this showing, it’s hard to tell whether that’s true.

An hour or two later, and up past the doorway smokers, chatterers and people wolfing bags of hot chips, and through the narrow corridor crowded with plaid and rad-dads, London singer Duke Garwood is on stage with his band. Garwood’s murky, instinctive blues has him teasing out rung harmonic notes from a hollow body guitar that seems to be constantly on the edge of being blown apart by swirls of internal feedback. It’s a treacle-heavy and stately performance that at times channels Ali Farka Toure’s hypnotic, playful Niger-Delta blues and at others Dylan Carlson’s sombre desert-noir.

Later, Mark Lanegan emerges out into a still blue light, accompanied by guitarist Jeff Fielder to open with ‘When Your Number Isn’t Up’ from 2004’s Bubblegum. With eyes clamped shut and the tendons of his hand tensed around the microphone, the atmosphere is brooding and the reception is warm, with the capacity crowd (bar a group of women by the bar who eventually pipe down) silent in the flint-struck rattle of Lanegan’s careworn baritone. Before long, the rest of Lanegan’s band joins him, apparently a man down after their bassist was admitted to hospital, but juggling instruments around admirably. Their playing is in turn sparse, with high guitar notes like electricity crackling off telephone wires, and then full, rich and bludgeoning, with a series of grungey torch songs lifted by stabs of synthesised mellotron, and Lanegan still and seethingly intense in the middle of it all.

More surprising, perhaps, to anyone who hasn’t followed Lanegan’s most recent albums are the synth and drum machine heavy songs drawn from last year’s Phantom Radio. Live, the beats (programmed from the iPhone app Funkbox, apparently, I can’t figure out whether this is inspiring or slightly disappointing) are pummelling, and songs like ‘The Killing Season’ take on a Gary Numan-like intensity that is missing on record. Duke Garwood is back on stage for the encore, smiling in the wings as they run through ‘I Am The Wolf’ from Phantom Radio in a loose, rolling lope, and the crowd beam back, enthralled.

Sunday afternoon, and the mist is hung like a white curtain pulled halfway up the hills around the town. Underneath, it’s like walking through a cloud, the raindrops a glistening surface sheen on every exposed surface, picked out in the Calderdale colour scheme: mottled browns, mossy greens and burnt reds. It’s nice to duck out of the weather, and into The Little Theatre to watch a double bill of Heavenly Films, both imbued with different forms of saturated nostalgia.

Released last year, How We Used To Live melds BFI archive colour footage of London shot between the 1950s and 1980s – largely taken from tourist films, and those about the royals – to evoke a city that was "no longer postwar but pre-something else". Written by St. Etienne’s Bob Stanley and writer Travis Elborough, directed by Paul Kelly, and set to Pete Wiggs’ subtle, electrified score, the archive clips are cut from a period broadly bookended by the formation of the Welfare State and the building of the Festival Theatre at one end; and the advent of Thatcherism and the construction of Canary Wharf at the other.

This is a film made in politically austere times, and has a definite warm nostalgia for the culture and landscape of this timeless smudge of post-war London, yet it wears its politics relatively lightly. And, whilst the overarching storytelling through the archive is skilfully done, most of the individual clips have something interesting or beautiful about them: a sailor singing shanties on a concertina to a group of children, with sailboats lining the Thames to Tower Bridge behind; steam engines being cut down in cartwheels of sparks during the Beeching cuts; a tower block carpark in the snow, looping patterns drawn in black slush by car tracks; and pop mogul Mickie Most out jogging in dress shoes, chocolate brown shirt and dark sunglasses (predictably, this gets a decent laugh from the crowd).

There are more laughs in the screening of Lawrence Of Belgravia, Kelly’s intimate and bleakly hilarious portrait of Felt’s lead singer. Lawrence bemoans that if only he could meet Kate Moss then they’d probably get married and open a shared bank account where "she could put in her millions, and I’d put in my dole money. I could take out £250,000 to make a record." But despite critical acclaim for Felt and Denim, fame never quite arrived for Lawrence. Why? "Because John Peel didn’t like it" Lawrence reckons (he went as far as to make the late DJ send back the 7" promos he’d been sent). Now leading Go-Kart Mozart, ("we’re a band for hire, we’ll go anywhere, all danger zones"), we see Lawrence touring small venues, driving other bands, and being evicted from his flat, all whilst keeping alive the (perhaps delusional, perhaps not) dream of the public finally cottoning on to his genius.

Back over in The Trades, new Heavenly signings Hooton Tennis Club slope on stage. There’s more than a touch of Felt about the young Liverpudlians and their endearingly shambolic and hazily melodic tunes. The drummer chides the guitarist about his tuning ("I only put these strings on today!") and a pedal tuner is unplugged and passed across the stage. No matter, really, there’s definitely something about this band, and new single "Jasper" is a highlight, all woozy Guided by Voices melodies and Malkmus-esq lead-lines shaken between dissonance and golden harmony.

H Hawkline (or, Huw Evans in real life) writes tricksy art-pop songs that slowly get under your skin, and tonight, flanked by Stephen "Sweet Baboo" Black on guitar and Guto Pryce (Gulp, Super Furry Animals) on bass, he’s on good form, running through a set drawn largely from the upcoming LP In The Pink Of Condition. The lithe, propulsive ‘Everybody’s On The Line’, is picked out with washes of psychedelic colour, and Evans sings "bring summer back" in a rich and laconic, baritone Welsh drawl under saturated yellow light on ‘Rainy Summer’. They end with ‘Black Muck’ from the Black Domino Box EP, the lines tumbling out with fizzing energy, and the drummer dropping a stick but – impressively – keeping up with the runaway band with one hand.

At the end of a long weekend, The Trades band room has filled up for the final set from Stealing Sheep. The stage set-up for the three-piece – cowbells, chimes, lapsteel, bells, an array of keyboards – looks a bit like the ‘miscellaneous’ section from an instrument shop, but the slightly ramshackle edge to the band’s live shows of a year or two ago has been replaced by something tighter, heavier, more together, more exciting. They’re nothing short of fantastic: trading smiles as their peals of highlife guitar, 808-precise runs of cowbell and toms and the subterranean synth lines evoke Julia Holter by way of ‘Stop Making Sense’ era Talking Heads, and the exuberant dub-post-punk of Explode Into Colours.

Two new songs, ‘Apparition’ and ‘Not Real’, from their upcoming LP (due in April) are huge, and make sense of the quote the band gave in a Quietus interview a couple of years ago that their ideal line-up would be "Beyoncé in Captain Beefheart’s band."

Between songs a pulse of delayed sine waves flutters off into the condensation-thick wooden rafters. "I quite like that, but I don’t know what it is!" jokes keyboardist Rebecca Hawley. "It’s a cheap delay pedal, is what it is!" comes the wry reply from across the stage.

A lone women at the front of the stage has her hands in the air as the band sing a beautiful wyrd-folk dirge (‘Evolve And Expand’) with nylon guitar and shimmering electric drones, and circular projections like dividing cells in a petri dish flex overhead. After collaborating with the Radiophonic Workshop at last year’s Branchage Festival in Jersey, the band locate the trance-ritual heart to Delia Derbyshire’s ‘Ziwzih Ziwzih OO-OO-OO’, the robotic tape loop voice ("praise to the master" reversed, apparently) sung in close, forceful harmony. Leaving the stage after the euphoric CocoRosie does Merseybeat vibe of early single ‘Shut Eye’, Hawley pauses to smile at the crowd, "go to bed, you must be shattered!" Aye, everyone probably is, but as the crowd peels off into the damp night, there’s no doubting the rejuvenating effects of four days and nights of bands and films from a label in fine health.