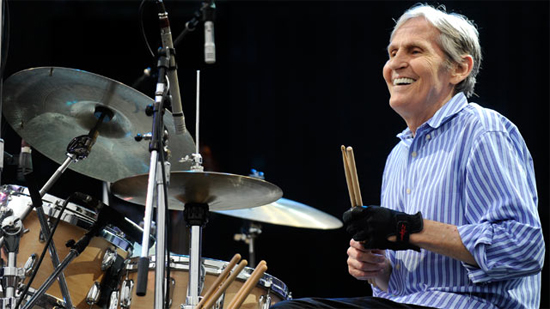

Tributes to Levon Helm, the former drummer and singer with The Band who died this week from throat cancer at the age of 71, have been widespread and perceptive. But the whirlwind that was Helm, as both man and musician, is best experienced in sound and vision. This was a man who was, after all, a doer, not a theoriser, and whose life was so beautifully and emphatically lived.

Thankfully, there are two remarkable renderings of Helm on screen that are both illuminating and profound – and that’s aside from his many dalliances as an actor. Firstly there is, of course, Scorsese’s famed documentary of The Band’s 1976 farewell concert, The Last Waltz. While the overwhelming high regard it’s held in is understandable, this film is also open to accusations of overratedness, what with much of its appeal coming from the fact of its extraordinary cast and the clearly dispirited energy of Robbie Robertson. But Helm throughout is a beacon of soul and enthusiasm, arguably the centrepiece of the film, all rippling muscle with a workman’s tan and newly embedded crow’s feet. There is plenty more footage of Helm in the throes of his vintage years – in Bob Smeaton’s Festival Express, shot in 1968, at Woodstock – but The Last Waltz perhaps shows his stage presence, unusually strong for a drummer.

Secondly, there is the superb 2010 documentary Ain’t In It For My Health, which deals with Helm’s final years living in Woodstock, NY. The film depicts life with his family and friends and his famous Midnight Ramble sessions and tour. It shows off his attitudes towards everything from farming to The Band’s legacy, and his amusingly astute disdain towards winning a Grammy for his 2007 LP Dirt Farmer. The film offers an abundance of cigarettes, warmth and excellent music. Most touching is a scene where Helm, with his half-voice reduced by the cancer that eventually claimed his life, croaks out Leadbelly’s ‘In The Pines’ to a new-born grandson in his mother’s arms. Thirty-four years after The Last Waltz, his impassioned authenticity remained.

And it is because of that authenticity that Helm will also be remembered for being involved in one of the most long-running and tedious feuds in rock history with Robbie Robertson. The reason, as Barney Hoskyns succinctly put it in Ain’t In It For My Health, was to do with the ingredients that made up The Band’s seminal style. In a band with such an even distribution of talent, Helm not only played drums and sang, but provided the knowledge and innate feel for the music from his native South (Helm coming from Arkansas). Chief songwriter Robertson, along with the other four members a Canadian, was enthralled with this music and used Helm as both instructor and muse. Helm’s main gripe for decades was that royalties did not reflect the weight of his contribution in this way, as Robertson dominated the group’s financial rewards. Helm was also strident in his rage at the treatment of other band members.

This loving devotion to his friends in The Band over the years is another thing that should not be forgotten. Helm was on hand when Richard Manuel, singer and multi-instrumentalist, killed himself in a Florida hotel room in 1986, a devastating and lasting blow. He was also left distraught upon Rick Danko’s death in 1999 and speaks of both men in delicate and tender terms in Ain’t In It For My Health. His friendship with organist Garth Hudson, now the only surviving member besides Robertson, persisted to the end, with Hudson a regular at the Midnight Ramble shows in Helm’s barn.

It would be crass to dwell further on the Helm-Robertson rift, particularly with Robertson visiting Helm during his last days. He said, “Levon is one of the most extraordinarily talented people I’ve ever known, and very much like an older brother to me”.

Another, more uplifting question might be which song features Helm’s finest performance as either vocalist or drummer. As far as Helm the singer goes, obituaries in leading papers have mulled over ‘The Weight’ (on which Helm can also take credit for some wonderful lyrics), ‘The Night They Drove Old Dixie Down’ and ‘Rag Mama Rag’ – all fair enough.

Perhaps his greatest moment, however, was on ‘Up On Cripple Creek’, where he was called upon for both his voice and some sterling time-keeping to keep up with Hudson’s extraordinary feats on clavinet. A mention must also go to ‘Jemima Surrender’, and for the restrained pulse his drumming achieved on ‘Chest Fever’.

It’s true Helm was never in it for his health, but throughout his life he always appeared benevolent and absolutely sincere, and his massive contribution will linger on.