In opener ‘Spacelab’ an image of the Evoluon flies over the heads of the audience. To be honest, the UFO shaped building in the Dutch city of Eindhoven is appropriate for visuals that attempt to express the ultimate challenge of space: being infinite and yet ready to be explored. Incorporating the venue in the opening visuals of the show could easily be mistaken for something that is merely a nice touch; a credit to the remarkable place where the group are playing. Truth is, the Evoluon is the only place where Kraftwerk’s music really makes sense.

Let’s go back to the 50s, the decade of the Marshall Plan, which guaranteed the reconstruction of Europe. In 1952 The European Coal and Steel Community was created, the first step to the federation of Europe that was established after the Treaty of Rome in 1957. The Second World War seemed far away and despite the the Iron Curtain splitting Europe in half, the future looked bright. The optimism cumulated in the World Fair in 1958 (called Expo 58) in Brussels, the new capital of Europe. One of the most, perhaps the most, astonishing contribution was the Philips Pavilion, designed by Le Corbusier. The idea for the building came from Iannis Xenakis, specifically his composition ‘Metastaseis’.

The pavilion turned out to be one of the first real multimedia installations. Within the building, which consists of nine hyperbolic paraboloids, Edgar Varèse’s ‘Poème Électronique’ could be heard through speakers set into the walls. Rapidly changes images of technologic progress and the horrors of mankind were projected on the walls, creating a rich spectacle that the Canadian media theorist Marshall McLuhan would describe as an acoustic space: time and space disappearing in a non-linear story. At the entrance and exit Xenakis’ ‘Concret PH’ was heard.

One of the 41 million visitors of the expo was Ralf Hütter, one of the founding members of Kraftwerk. The Philips Pavilion made quite an impression on the young Hütter, who was twelve at the time. It is not that difficult to the the connection between the naive belief in the future at the end of the 50s and the work of Kraftwerk MK II and MK III – the Kraftwerk of Autobahn, Radio-Aktivität, Trans Europa Express and the Kraftwerk of Die Mensch-Machine and Computerwelt. Although the music sounded astonishingly new and fresh, Kraftwerk was in fact trying to regenerate the future, thus the 50s.

Back to Philips, the multinational behind Le Corbusier’s pavilion. During the 50s the Dutch company was led by Frits Philips who believed that the company had an obligation to the world to make it a better place through technological progress. As well as the Philips Pavilion at the Expo 58, this idea was further realised by the NatLab, the Philips Physics Laboratory, where all kinds of research took place. This lead to some major inventions, including cassette tape and the compact disc. While Karl-Heinz Stockhausen was experimenting with sine waves, in NatLab Dutch composers Dick Raaijmakers and Tom Dissevelt were using synthesizers to make electronic music. Songs Of The Second Moon, composed in 1957 by Raaijmakers as Kid Baltan, sounds like Kraftwerk only twenty years earlier. The same goes for Syncopation by Dissevelt. Both composers were way ahead of their time, you could say. But that isn’t the case at all. Their music is in essence pure 50s: it’s longing for the future, reaching for it with both hands.

Although we tend to see the 60s as the decade of social change and emancipation, you could argue that the future stopped around 1960. With the introduction of new electric media like television the world became a global village at a pace nobody was able to handle. From the 60s onwards we were congregated in a one dimensional society – as Herbert Marcuse called it – where nobody, especially governments and big companies, could be trusted and only consumption could give relief. The Iconic building Evoluon that architects Louis Kalff and Leo de Bever built to mark the 75th anniversary of Philips in 1966 is in essence nostalgic. Shaped like a UFO, it was meant to show the technology Philips invented to the public; the building reminds one of the time in which there still was a strong belief in the future and in technology making the world a better place. In 1966 that dream was already shattered. A few years later Philips would release the first four Kraftwerk records.

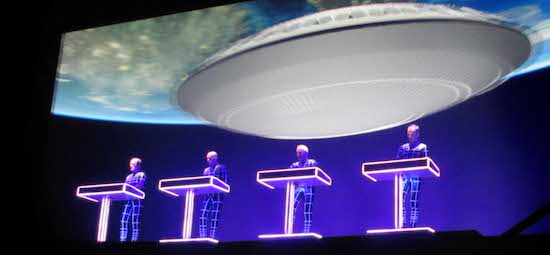

The music of Kraftwerk mark II and III is like the Evoluon. It is 50s nostalgia. It is longing for the past. Sociologist Fredric Jameson wrote that "sci-fi is nostalgia for the future". If that’s true than Kraftwerk is sci-fi and Evoluon is too. The story goes that Hütter, the only remaining original member in the band, himself wanted to perform in Evoluon. The combination is sci-fi to the max, and breathtaking, too. With the audience (only 1200 each show) gathered at one of the terrace rings, Hütter and his three Kraftwerk colleagues are standing behind their desks in the top of the building. Behind them the 3D graphics are as nostalgic as the music. They breathe an optimism that maybe is more compelling today than ever before. We are in need of dreams, in solutions for problems we do not understand yet.

Kraftwerk doesn’t give answers but maybe it tells us where to look, just like the Evoluon does. ‘Trans Europa Express’ tells the dream of the European Union: everybody connected through technology. Just like ‘Autobahn’ does, celebrating a free Europe without borders and only freeways to drive and drive on. In ‘Tour De France’ the essence of cycling – perhaps the king of sports – is shown: the lonely hero pushing his own physical and mental boundaries in a time where money and winning have become inferior to self-realisation. And then in ‘Heimcomputer’ (home computer): "Am Heimcomputer sitz ich Hier und programmier die Zukunft mir" – "I program my home computer, beam myself into the future".

After nearly two hours the UFO returns home with a clear message: we can’t go back to the exciting world of the 50s, but we can learn from the way that technology was perceived in that decade of progress and believe in the future. We still have Kraftwerk, the music made in NatLab and Evoluon to remind us of that. Now let’s program the future.