After 50 years, the buzz is back. Fans of The Texas Chain Saw Massacre have been clambering for an official soundtrack of Tobe Hooper and Wayne Bell’s terrifying score, and it’s finally happening through Waxwork Records. It’s been a long road for Austin native Bell, who not only composed Chain Saw’s score with the late director Hooper, but also handled its sound design. And he knows there’s a ravenous audience for this that have been girding their loins for half a century.

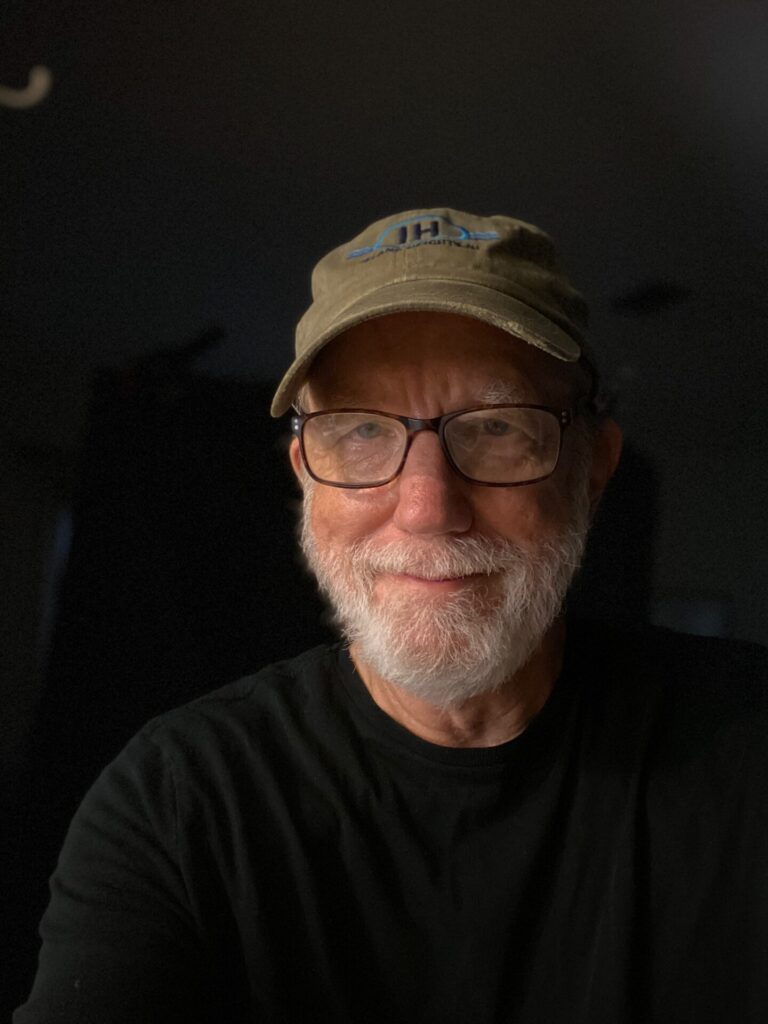

“I’ve laid up onto a few conventions,” Bell tells me over the phone from Texas, “where all of the chainsaw alumni, both in front of the camera and behind the camera, are there signing autographs and meeting fans, and it’s pretty fun because the fans are a very happy lot. And the film is beloved so they’re just pleased as punch to meet us, and I’ve had more than one person say this inspired me to get into rock & roll or inspired me to do differently what I do without learning guitar or things like that. And so industrial music is a genre that leans on what we created, apparently it went a long way to influence that.”

Chain Saw has been seen as a commentary on the transformation of the industrial landscape in America through technology, and subsequently it’s more metal than Black Sabbath and Slayer put together. “It’s true,” Bell says, “that a lot of the sonic quality is metal, but that’s the associative that helps your imagination. There’s not much in the way of wind instruments going in this one. I mean there are cymbals all over the tracks – I had two cymbals; an 18-inch Suspension cymbal and a 20-inch ride cymbal – and that metallic quality allows it to go further afield from just stinging. I did bring up a little bit of sound effects but not much. For instance, there is no actual sound of a chainsaw on this album, because the chainsaw is its own thing. That’s why there’s no music at the very end when Gunnar [Hansen, who played the iconic Leatherface] is dancing and swinging that chainsaw around. What a great sound.

“But in the opening, I do include sound effects, because there’s a piece of story that needs it. We’re in darkness and it’s night and you hear some kind of scurrilous activity going on, and I needed to sell the flash frame of the camera. I needed the real-world sounds of the digging and the crickets and the grunting and breathing of the hitchhiker and the camera click and the little flashbulb sound. So, the first images that you get to see are these still shots that that camera has taken of these body parts. And along with that is the stinger, which is not the first musical thing but certainly the most the first and still the most arresting. The first musical sound you hear is actually cymbals, but it’s not just this cymbal, it’s doing some kind of business a little, and someone pointed out to me that the first they thought it was a wind track. It’s atmospheric and in a way just does the job that a wind would do if you were trying to imply wind in a haunted house.”

Listening to the music in clear remastered sound just re-emphasises how unsettling and disturbing Hooper and Bell’s score actually is, and how it blurs the line between music and sound design. Ruminating on the scene where Kirk and Pam go up to the house, Bell says: “As they’re approaching the house, there’s no music. And as Kirk is going in the house, there’s a wind track. And it kind of does the job in a way, sound effects can be very musical and do the same job that music does. And that wind track is kind of a good haunted house wind. And then there’s also the pig sound. That pig sound is actually my father, imitating a pig.”

There were no electronics used in the score, and Bell says that “we wanted to be looser, more abstract, as opposed to, you know, tonal western style. Of course, there’s another reason and that is that there was no budget.” Money seems to crop up again and again, and Chain Saw really was the little film that did, using those financial restraints to get an experience as grungy as possible. But it also meant that Bell wasn’t able to participate in the final mix.

“We mixed at Todd-AO, a wonderful sound house in LA. Tobe as a young filmmaker had a good experience out there and had been mentored a bit by a sound mixer named Robert “Buzz” Knudson, who won an Oscar for mixing The Exorcist. Buzz arranged a sweetheart deal at Todd, but they had to mix it very fast because we were so low budget that there wasn’t money to pay for anybody but Tobe to go out there. It was a classic film mix of the time, done fast, and the end result was a mono track. They did a great job, Buzz, and the second mixer Jay Harding. They were pros and they work really fast.”

“People have been after me for decades,” he says when he talks about the soundtrack finally being released, “and I would get phone calls and emails, often from young upstart record labels thinking wouldn’t it be cool if they got to be the one that released the soundtrack for the Texas Chain Saw Massacre. They would reach out to me, and I would say ‘thank you very much, that’s not happening now, but if it can I’ll seek you out,’ and I would let Tobe know that I had another one. Tobe didn’t seem to have any interest. And since it’s both of us, neither of us could put it out by ourselves. I had gone to Los Angeles after Chain Saw and worked for a while and made the choice to come back to Texas. In fact, I was out there with Tobe and we did the score to his next picture, which was Eaten Alive [Hooper’s 1976 picture about a hotel owner who feeds guests to a local swamp crocodile] although the unofficial name in Toby’s parlance was Croc, with a double entendre. There are those that love it and I’ve even had requests to do a soundtrack album [for that film], but I don’t have any rights to that music. But we retained the right to our music from Chain Saw and finally I was able to put it out for people to hear.”

I ask him what his philosophy was when approaching putting the new release together. “To stay true to the original,” he says. The masters he found in an Austin archive were in surprisingly good condition considering they were five decades old. “The tapes that I was able to access were tapes that I recorded, and the only person that ever handled those tapes was me, because I also oversaw the dubbing of them from tape to a sprocketed medium. And so I was pleasantly surprised. I’ve been working in digital so long and away from the hiss of tape that I was afraid that they would be noisy. But in fact, they’re pretty clear, and that’s good because I didn’t want to do noise reduction unless it was really necessary. I could just play the stuff and duplicate exact edits that we did back then.”

There are, however, three tracks on the album that will be new to any Chain Saw fan, no matter how rabid. Bell calls them sketches, and they act as connective tissue for the album. “They’re just little sketches that aren’t actually in the finished picture. I’ve been wanting to do this for a while, so I thought just seeding it with these little short outtakes would be a good thing, and I hope that plays well for people.”

But he takes the whole thing as seriously as possible. “I felt a huge responsibility, because I’ve seen how beloved this film is and how beloved this soundtrack is. So I owed it to Tobe to do it right, I owed it to the music itself, you know, to present it as good as possible, and to the fans to deliver. When they hear that there’s a Chain Saw soundtrack, I want it to be something that they walk away satisfied with that, you know, ‘yeah, that’s it.’”

So how does he feel now that this chapter of his life is finally closing? “I’m ready to put it behind me. You know, it was just one of the things I did. But unfortunately, it’s the one famous thing. I’ve done a lot of really interesting stuff so it’s a drag that I’m remembered for this one thing, you know, from when I was quite young. I was 22 years old. But on the other hand, it is what it is. And it’s a good piece of film, so I can’t complain too much because it’s very effective and done on the cheap – certainly the score and the film in general are examples of necessity being the mother of invention and that limits can actually free you up. The story, the filmmaking, the image, the sound, this is a great example of the creativity that having only so much budget can result in.”

“I’m anxious to see what people think of the album. I’ve been pleased with the response so far and I will be interested to see how it works for people. I’m hoping that I delivered what they wanted. And then some.”

The Texas Chain Saw Massacre is released today by Waxwork Records