There’s a dank odour in the Friday night air of this corner – and you do feel a little cornered – of East London as we descend the steps from Limehouse Station onto Commercial Road. Fluorescent light emerges from the windows of the late-night off licences that break up the lines of shuttered shop fronts and plywood-boarded windows. A few hundred yards down the road from Limehouse Station, The Troxy sticks out like a manicured finger in a box of sore thumbs. If the rest of the area bears the scars of slow decline since the 30s, inside The Troxy it feels like it still is the 30s. The dinner-jazz aesthetic, combined with the venue’s surreal presence amid such crusty surroundings, makes for an apt location to mark the release of Steven Ellison’s latest flight of fantasy, Until the Quiet Comes.

Before that happens, FlyLo collaborator and tonight’s main support act Thundercat (aka Stephen Bruner) is imploring the crowd to make more noise, which they would if two thirds of them weren’t still queuing out of the Troxy’s glitzy front entrance. That so many people miss Bruner’s set is a shame. Arriving onstage in a thickly draped crimson scarf and a golden tabard with ludicrously flared-shoulders, Bruner looks every bit the eighties, parallel-universe, cartoon hero; more Master of the Universe than Thundercat perhaps, but that will certainly do.

Managing to incorporate two layers of rhythm and lead into his own basslines, Bruner (accompanied by drums and keys) is a far more impressive proposition than any of those trashy drums-and-guitar bands that decided they could do without four strings cluttering their low end. More than just displaying the technique that has earned him gigs with both Stanley Clarke and Suicidal Tendencies – it’s surprising to know that Bruner is a full time member of the veteran thrash band – this is a funky, soulful and immersive set from the man whose groove underpins much of Ellison’s cosmic venturing.

And then, as the queues continue to filter in, not much happens for a while. Those outside wonder what’s keeping them there, while those inside are left hoping; hoping that FlyLo appears onstage soon otherwise these drugs are going to have been a waste of time, and what’s with the decks being hidden behind a big white screen?

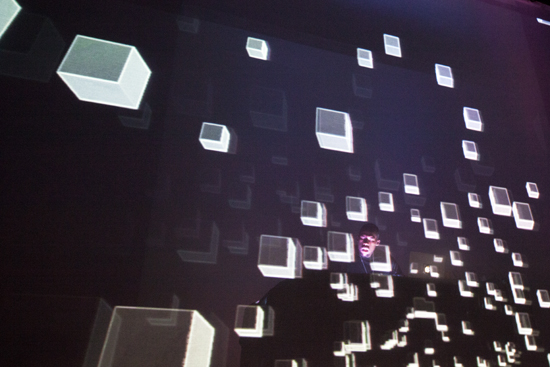

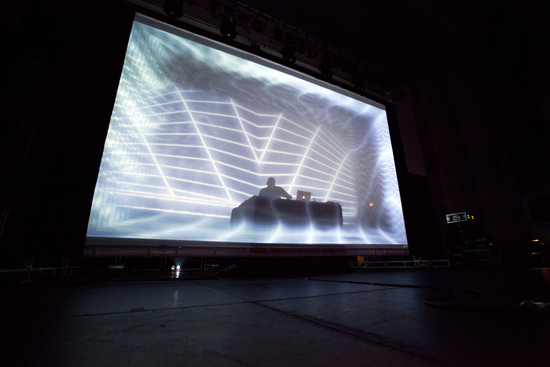

Eventually, half an hour late and after one false start, Ellison arrives, points a forefinger to the sky and shouts "LUNDUUUUN!" (as he will do periodically over the next hour and a half) while summoning the first rumblings of monstrous bass from the equipment in front of him. Instantly, attention is drawn to that big white screen, or rather screens, which have come to life. It’s a relatively simple setup – two screens display images projected from the front and rear of The Troxy’s stage, while Ellison works in the shallow space in between. The animations – developed by FlyLo associates Strangeloop and Timeboy (of course that’s what they’re called) – shapeshift constantly, morphing between marching, Kraftwerkesque robots, multicoloured Jackson Pollock splashes, throbbing neon orbs. It’s all stunningly well executed.

Even as individual layers, the two screens generate a three-dimensional existence of their own, separated by Ellison, who exists as a further 3D presence in between. The result is a collage of three (and bear with me here) simultaneous, three-dimensional fields that both exist independently of each other and bleed into one another. At its simplest, the effect is of Ellison trapped inside a giant, hi-definition screensaver. At its most elaborate it becomes a truly mind-blowing audiovisual experience, even for those with a journalistic responsibility to refrain from being quite as fucked as the majority of those present tonight. If anyone is having a bad time, it’s the photographers huddled in front of the stage, who are presumably wondering what to focus on, and how.

Musically, Ellison possesses the wizardry to hold his own amid the visual show; in fact he is sonically as well as physically at the centre of everything that happens onstage. Bass throbs feed laser pulses, thinner musical textures are echoed by clarity onscreen. And all of it feeds the mass of grinding, bouncing and gurning figures that bathe in Ellison’s glow. Ellison, despite bigging up the new album a handful of times throughout the evening, spreads his own material fairly sparsely between other tracks and samples. However, it is worth bearing in mind that, such is his lust for sonic playfulness, stepping onstage to simply play a succession of his own album tracks would be completely at odds with the spirit in which those albums were created in the first place. Far better to cut and splice, to form a kinetic, sonic landscape that will do those visuals justice.

When the album tracks do arrive, they do so as expansive, multilayered projections in their own right, bursts of transcendent sound that have found their way out of Ellison’s basement studio and now crackle and boom in the air. And who’s to complain, as we stumble back out onto Commercial Road to catch the first available night bus out of there, if among the evening’s spectacle we were also graced with cut-up, percussive transformations of ‘Baba O’Riley’ and The Beastie Boys’ ‘Intergalactic’?

Another Dimension indeed.