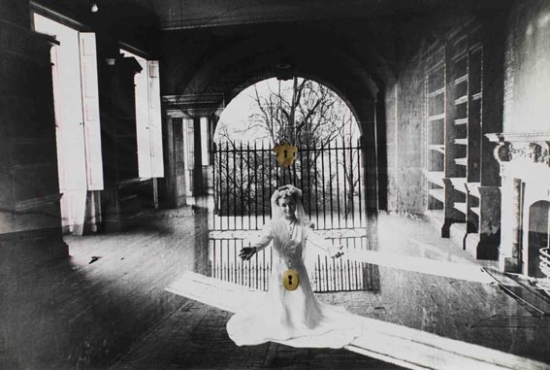

If the sight of a Georgian gun-maker’s shop in present day Soho throws your sense of time, the image displayed in its window will go one better and throw your sense of sense. A Jacobean country house with a woman’s face as its nautical figurehead, a jewel for its third eye, guarded by a headless body:

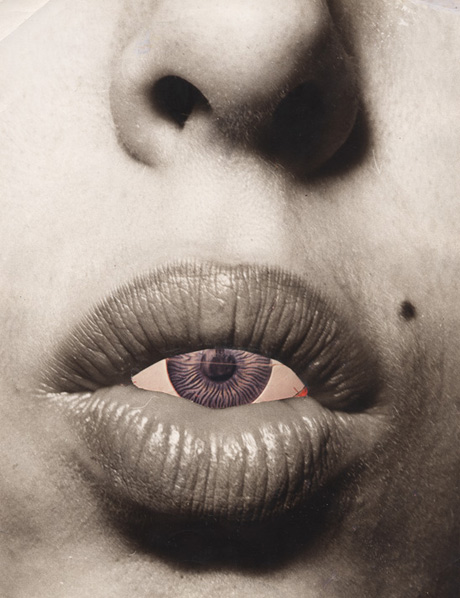

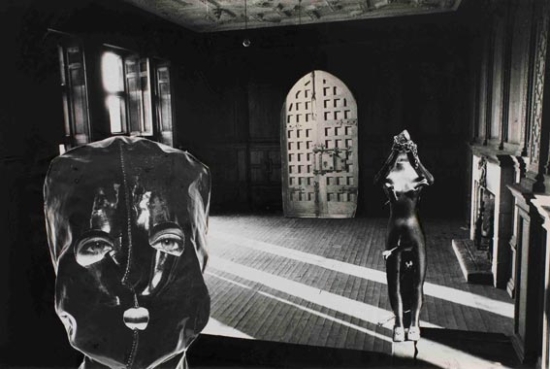

Through the shop window an eyeball peeps out from inside some lips. Across the room there’s a golden head draped with chains like slender dreadlocks, lips sealed with a small key. From the wall a blood-red mouth emerges, letting drop a ruby drip.

Devotees of that decade’s cultural treasure will immediately clock Penny Slinger’s photo collages and sculptures as products of the 1970s. Their pop art boldness and exploration of self and myth feel familiar from Angela Carter’s fiction, Alejandro Jodorowsky’s films, Roxy Music and Eno record sleeves. The models’ looks and the ubiquitous lips could have been taken from contemporary fashion mags and adverts from the other side of the looking glass.

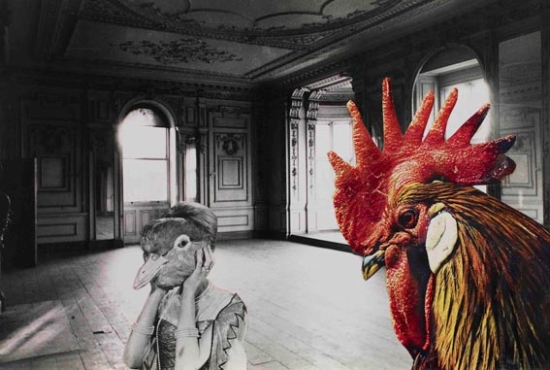

It’s easy to forget how rare it was then for women to call the shots on such imagery. Slinger also art-directed and performed in Jane Arden’s The Other Side of the Underneath – the only British feature film directed solely by a woman in the Seventies. The variety and nuance in feminist art (from any era) is often forgotten too. Slinger’s naked bird-people and lips within lips don’t rebut the hetero male gaze; they disregard it. She assumes her psychic space and explores it freely. There’s a lightly worn frankness, a seemingly un-British ease with sex in the images that haunt this creaky old shop. (Linder Sterling’s approach in her punk-era collages makes a nice contrast).

Their gothic, mythic and esoteric aspects, however, reach across time. The surrealists also gorged on this stuff. Max Ernst’s avian pulp collages (like Une semaine de bonté ) were a starting point for Slinger’s own. People still tend to think ‘surrealism’ means wacky, colourful paintings. But the term’s probably best used to connote a quality rather than a style: anything that pushes the primitive, magical buttons in your modern, rational mind is surreal. The multimedia, magpie movement claimed everyone from Edgar Allan Poe to utopian socialist Charles Fourier for its canon; once it had a name you could spot it anywhere, anytime.

Other common misconceptions are that that women played a marginal role in surrealism, and that it’s never been a significant force in British culture. Leaving aside our knack for popular surrealism from Lewis Carroll to Vic & Bob, many of the movement’s strongest female artists happened to be British: Leonora Carrington, Eileen Agar, Ithell Colquhun, the still-neglected Emmy Bridgewater. Their cheerleader, Roland Penrose, went on to co-found the ICA, where he ended up championing the young Slinger’s work.

Pop music itself may (often unwittingly) have been surrealism’s greatest delivery system, its parade of sound and vision bypassing the rational mind with ease. Naming surreal moments in pop would take forever, but during the time these images were produced glam rock, the Parliafunkadelicment thang, Kate Bush and punk all happened. There must have been something in the air.

Hear What I Say runs until 30 October at the Riflemaker gallery, London

_See Penny Slinger’s surrealist works on her website_

All images copyright Riflemaker