Now celebrating its 50th anniversary, Edinburgh-based art gallery Fruitmarket presents the annual Deep Time festival of new music this November. This year’s festival, curated by vocalist, movement artist and composer Elaine Mitchener, imagines conversations between two famous New York artists who each had work on display at the gallery in 1984 – John Cage and Jean-Michel Basquiat.

Deep Time begins on 27 November and continues through 30 November, with a lineup of interdisciplinary and musical performances by artists including Apartment House, Rie Nakajima, NikNak, Aidan O’Rourke, Mitchener and her frequent collaborator, Dam Van Huynh, among many others. Accompanied by the concerts are intimate conversations that illuminate the dinner table-like, conversational ethos behind the festival.

We caught up with Mitchener in advance of the event to talk about her curatorial perspective and why she wanted to use Cage and Basquiat as inspiration, her world premiere piece, her love of Julius Eastman, how his work continues to resonate today, and more.

How did you get involved with the Deep Time festival?

Elaine Mitchener: I heard about Deep Time through some friends who performed in it last year. Sam Woods, who is the curator at Fruitmarket Gallery, dropped me a line and asked me if I would be interested in performing at the festival. She talked about how Jean-Michel Basquiat presented his first solo show in an institutional organisation in 1984 and Cage had also presented work in the gallery in 1984. There’s no evidence that they met – their exhibitions did not coincide – but I’m sure Cage had heard of Basquiat, and Basquiat knew of Cage and in fact admired his new approach to music. So I thought, “Wouldn’t it be great to have a festival that tapped into these two artists and those who orbited around them and imagine this is this huge conversation?”

Sam also shared some reviews of both exhibitions at the time. They were effusive with Cage. With Basquiat, they were incredibly dismissive. I’d like to say borderline racist, but actually, you could just sense it. They didn’t know what to make of this Black, American, New Yorker, young graffiti artist. I thought it’s time to readdress that. For me, it’s not about hierarchy – they’re equals. Let’s present them as such to correct that wrong that happened 50 years ago.

It’s a huge task to imagine a conversation between John Cage and Jean-Michel Basquiat and then pick artists who are going to further that conversation. How did you come to that?

EM: I didn’t want to lead with the idea of “I’m the curator of what I say goes.” I’m just going to be excited and intrigued by the programming ideas of the artists that I’ve approached. There are people that I know who have performed the work of John Cage a lot, like Apartment House. The artistic director, Anton Lukoszevieze, is very knowledgeable about Cage, but also about other things. Anton came back with a Cage piece called Score (40 Drawings By Thoreau) And 23 Parts, and he talked about David Wojnarowicz, who was in the orbit of Julius Eastman. One of his works is said to have influenced a painting that Jean-Michel Basquiat then went on to make. So there were these Venn diagram-like connections that really intrigued me.

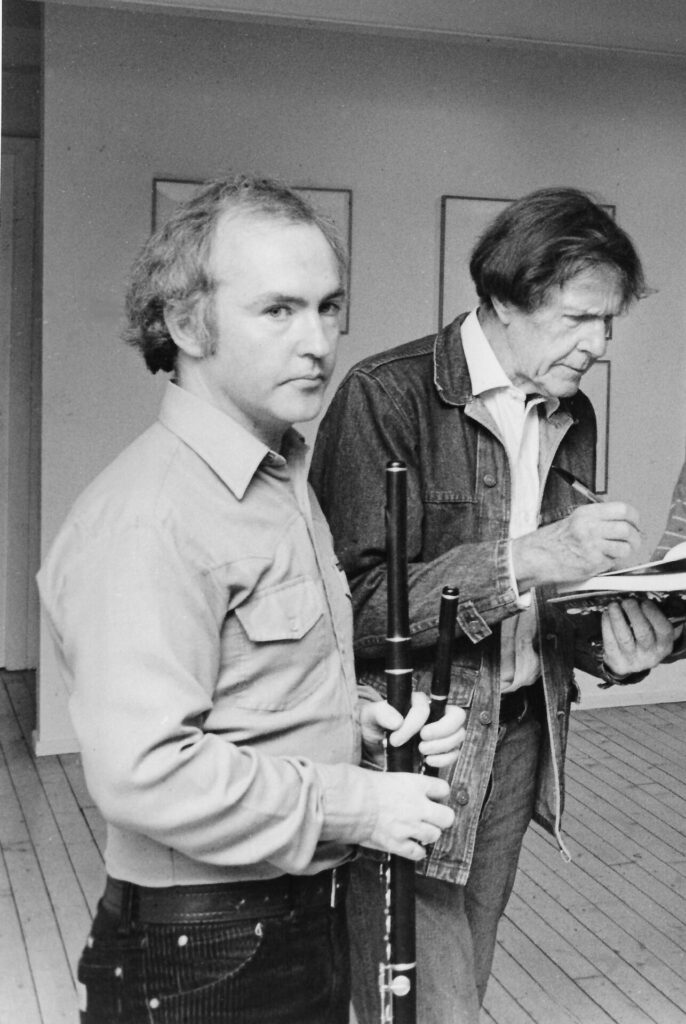

Rie Nakajima is a wonderful artist — she’s got this incredible way of using objects to transform a space. Her piece, which is called The Detail Of The Whole, is a performance installation that engages with both Basquiat and Cage’s interest in found objects, images and sound. We also created a new ensemble, Scottish Circus Ensemble, to perform the same night as Rie. Scottish Circus is a piece by Cage that came about when Mark Francis, who was the curator who brought Basquiat and Cage’s work to Fruitmarket in 1984, introduced Cage to Eddie McGuire of The Whistlebinkies, which is a Scottish folk band. They got on like a house on fire, and he asked them to each come in and just play some traditional tunes. A commission came out of that for a piece that premiered in 1990. I was talking to a Scottish avant folk musician, Aidan O’Rourke, and I said, “What I’m interested in is who is playing Scottish folk music now, and how is Scotland representing itself? It’s in a much more diverse place than it was 50 years ago. Can you find folk musicians who are living in Edinburgh or Glasgow, who are not necessarily white Scottish folk musicians, but they can also bring in their own folk heritage, and let’s see where that takes us?” So, that’s what we’ve got. It’s a very diverse group – very diverse in their heritage and also their musical approaches.

On the first night, I’m in conversation along with my longtime collaborator, Vietnamese-American choreographer Dam Van Huynh. We’ve worked together for 10 years on and off, and he approached me with this idea about Eastman – he wanted to use Eastman’s life story and his legacy as a departure point for a new piece. I learned so much more about Eastman through the process of research [for the piece]. I’ve rediscovered work that I’d read about but didn’t really listen to, because we know the famous pieces and the provocatively titled pieces, but there are other works where scores don’t exist, or maybe only a recording exists. This new piece is also a celebration of Blackness, of being who you are, of your sexuality. In Eastman’s case, being homosexual to the fullest, being Black to the fullest, being a musician to the fullest, and also not wanting to be held. He says, “I emancipate myself from the bind of the past and the present.” It’s that thing of always moving forward. I’ve learned a lot about myself from through this process of working on this piece with Dam.

What did you learn? And, what are you taking away from that experience?

EM: One of the things that really struck me is the shared experiences. My life hasn’t been as extreme as Julius Eastman. I’m not on the streets, I’m not impoverished – I’m not rich, but I’m not impoverished. It’s more about this frustration, the urgency to be yourself, and the urgency to be able to creatively be yourself and to present what you believe in. His interdisciplinary approach to making work has given me confidence to continue doing what I’m doing. It’s that boldness as well. Eastman wouldn’t let anything stop him from being 100 per cent unique, 100 per cent himself, and that’s the massive lesson that I’ve been learning throughout this process. I wasn’t expecting to, but things speak back to you when you’re doing them. Sometimes you don’t have a chance while you’re learning or developing a piece to answer those questions, but on reflection, I think it will sit with me for a very, very long time.

You can’t predict when you’re going to have those moments of questioning and learning about yourself, but it’s really special when it comes through art.

EM: Absolutely. Also, Dam was inspired in response to the writer Mitsuye Yamada’s observation that “invisibility is not a natural state for anyone.” She wrote that as a Japanese refugee in a concentration camp in the United States facing racial discrimination. That quote punches you right in the gut, because it’s absolutely right. There’s nothing you can’t disagree with that statement. Moving Eastman is also helping to ignite a necessary discussion about who controls the narratives in recording history, and who possesses the authority to tell their stories. The general narrative on Julius Eastman is about him being homeless, the controversially titled but politically charged piano series and n-series, and also his very vibrant and open sex life, his homosexuality, and his drug dependency. People tend to focus on the sad aspects of his life. But I don’t think he even felt sad about his life – he’s like, “Hey, you know, I don’t live anywhere, I’m a wandering monk. I love composing in the bar. I like going to bars. I like drinking. I love love, I love sensual things.” This is a man who had a really strong sense of himself. These are things that we’re trying to tease out and present in a more positive way.

It also struck me that these two geniuses, [Eastman and Basquiat], for whatever reasons, were living in a park, homeless. Two Black men facing daily abuse and suspicion – you can understand why substance abuse would happen, because you just have to numb the pain of it. I’ve been reflecting on that for a while. What really struck me is that these two remarkable individuals ended up living rough at some point in their lives – what’s happened to society that can allow that, and what’s happened to the artistic creative community that can allow that to happen as well? Because we call ourselves supportive, but it doesn’t always happen.

There’s so much about the infrastructure not supporting artists, especially artists of colour and especially in the States, where there’s not a lot of social welfare. I think that’s why there is such radical defiance, that radical joy coming out in this music. Despite all of that, they could still make art and they’re still geniuses. Now we’re getting a moment to look at it.

EM: Absolutely. I’m trying to focus on the joy now, because I think there was even joy in the sadness. And they were such brilliant minds as well and questioning society and holding society to account through their work. There’s a real strength of character and boldness in doing that, particularly when you know that just because of the colour of your skin, you’re hated or under suspicion. I feel this festival celebrates their genius and also their openness and love.

Elaine Mitchener is the curator for this year’s Deep Time Festival, which takes place from 27 to 30 November at Fruitmarket in Edinburgh. For full details and tickets, click here.