Divorce, speed dating and a day job at John Lewis are unlikely subjects for a noir thriller. But what makes I, Anna a little bit different from the average is that it strays into areas of life where that classic genre – even in its ‘neo’ incarnations – doesn’t usually go. Based on Elsa Lewin’s novel set in New York, the movie relocates the story to a well-heeled but lonely London, oriented around the brutally grandiose Barbican building. Here, a typically jaded, sleep-deprived detective falls for the suspect of a crime he’s investigating. A single woman in her sixties, she makes for a much less typical femme fatale.

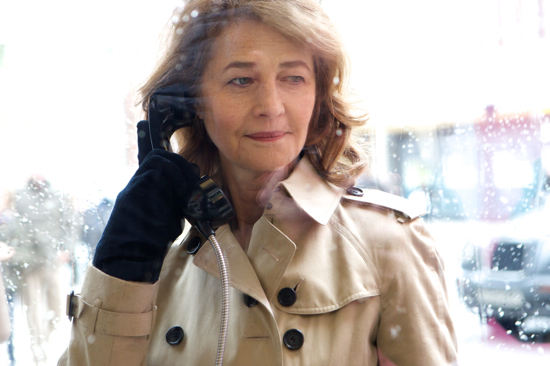

I, Anna is the debut feature of writer-director Barnaby Southcombe, whose mother, the eminent English actress Charlotte Rampling, takes the starring role. The pair describe working together as "oddly normal", because "we’re both professionals". Equally, when the Quietus meets them, their real-life relationship seems "oddly normal" too, with Rampling occasionally stepping in to finish Southcombe’s sentences, as most parents tend to do.

Whereas Rampling has an illustrious, intermittently controversial cinematic career behind her, Southcombe is only just starting out in his, having previously worked in television. The London he beautifully, but darkly, depicts here is a personal one. "I grew up with mum in France most of my life, and then I came to the UK for the first time to go to university. And I found London this incredibly, overwhelmingly large and daunting place… and it was very much that feeling that I wanted to capture. How, in a city of nine million people, you can feel so alone. And how the chances of meeting somebody seem so impossible, even though you have this gulf of opportunity."

This is a predicament that Anna (aka ‘Allegra’, to her prospective dates), faces. Having split with her husband, she reluctantly forces herself to "get out there" again, by attending faintly excruciating singles nights. At once aloof and utterly vulnerable, Rampling plays the part exquisitely, acting out a middle-age experience that’s increasingly common, yet stubbornly absent from the not-so-silver screen.

It’s this absence, Southcombe explains, that he wanted to address: "I’ve found we all share the same insecurities and the same desire and need for love and companionship and affection, and that journey – or that struggle – becomes more potent the older you get, and I think that’s something that happens to all of us. And to not have that reflected in the cinema is a shame. It’s great to see beautiful young vampires running around, having babies and stuff. It’s just that I also like to see the society I live in reflected."

It might seem like an unusual theme for a young man to want to explore, but Rampling understands it: "I think the big interest too is a younger man looking at an older woman – It’s like with François Ozon when I did Under the Sand, when I was in my early fifties and he was in his early thirties. He wanted to watch an older woman, who was in a state of grief. It’s a younger generation looking into the future of what relationships are. I think it’s very powerful."

Powerful this impulse may be, but it’s certainly not popular, with roles for older women remaining thin on the ground. "There are very few leading roles," Rampling admits. "This is a beautiful leading role for an older woman – but there aren’t many of them, that’s for sure. There are interesting smaller roles – like in Melancholia, and another film I did with Todd Solondz, Life During Wartime…" At this point, Southcombe interjects, "You’ve done loads of stuff. But unfortunately, they aren’t leading…" to which she replies, firmly, "But that you need to accept."

"I’ve had wonderful leading roles. Now I can find these smaller roles, and then from time to time there might be a very beautiful leading role that comes, but it’s not going to be, probably, anything like as much as it was before… But that’s what happens when you get older. It doesn’t mean that you’re being forgotten. So you need to make sure that you’re not forgotten, you need to keep them interested in you, and be ready to play very different types of roles – roles that aren’t ordinary ‘older woman’ roles, like grandmothers… Of course, Anna is a grandmother – and I’m a grandmother – but I don’t play the ‘grandmother’ role, necessarily. I play it differently."

This difference, in the way Rampling plays her, helps to make Anna a fascinating, at times frankly terrifying, character. Soft, almost huggable one moment, then – with a mere twitch of her green eyes – brittle and deadly the next. Rampling calls it, "very moving sands. You get a flash, maybe, of her being fatale… What is going on in this woman’s mind? What happened? Why is she like this? She seems very attractive, why is she going to these single bars? What is this? It’s that moving sands feeling that makes for a film noir." "But", Southcombe begins to say, "femme fatales are…" and Rampling finishes, "fatale. That’s it – just that."

Southcombe continues: "Yes, they’re purely objectified. They’re only seen through the vision of the male protagonist – through his gaze. So I wanted to spend time with Anna without that. So of course, when you have a cop who falls for a suspect, who he’s following, you’re going to have to look through his eyes. But I also wanted to actually go and close the door, and spend time in her apartment, and see who she is."

This coupling of generic noir tropes with more ‘natural’ moments is reflected in I, Anna‘s soundtrack, which is part shadowy electronic score by French duo k.i.d. (Keep It Dark) and part love songs by Sheffield crooner Richard Hawley. The decision to include the latter, Southcombe recalls, was made in a moment of serendipity. "What I was lacking was the voice of these two [of Anna and Bernie, the detective played by Gabriel Byrne], of their relationship… I came across Richard Hawley, actually, on my iPhone – it was on shuffle – and this song, ‘Precious Sight’, came as if floating through the city, with this extraordinary melancholy voice, and I thought, could we have vocals on this film? And I added it in, and we all thought, God, this is it."

Strangely, it sounds as though the song’s writer was struck by a similar sense of fate. "I approached Richard Hawley and sent him the film with his music on it. He called me back at two in the morning and said that he loved it, and that he’d had this odd experience with his own mother who had gone to a singles evening and who had brought this kind of odd character back. [Hawley] happened to be walking past her house, and had seen through the window that things were not going particularly well, and had had to go in and extricate this man. So there was a strange kind of personal resonance for him."

It’s these kinds of strange personal resonances, picked out through the impersonal metropolitan gloom so ubiquitous in thrillers, which add depth to this movie, and save it from showing us simply more of the same.

I, Anna goes on nationwide theatrical release from Friday December 7.