Before you read on, we have a favour to ask of you. If you enjoy this feature and are currently OK for money, can you consider sparing us the price of a pint or a couple of cups of fancy coffee. A rise in donations is the only way tQ will survive the current pandemic. Thanks for reading, and best wishes to you and yours.

The live album – especially in rock and pop – is a curious beast, often seen as little more than a way of rinsing cash out of a dedicated fan base; a means to keep enthusiasm for an artist ticking over when they have temporarily lost contact with their creativity through "exhaustion", or a way of plugging the gap until a "real" album turns up. But given how much rock (and funk and soul and metal and any other genre that thrives on the promotion of ‘virtuoso’ musicians) is supposed to be all about chops, the mercurial talent of the idolised star, the supposed authenticity of the real experience versus the supposed sterility of the engineered artefact, this is plain weird. Surely the live gig or concert is the arena where frenzied love from their fans can push artists on to ever more stratospheric levels of creativity… it’s downright odd that most music fans don’t actually place more of a premium on live albums. Certainly it’s odd that these LPs don’t really have the same centrality to the genre that, say, jazz, classical and opera live albums do.

(There are things to take into consideration of course, like the idea of improvisation in jazz being generally much, much freer and exploratory than it is in rock and also a relatively high level of connoisseurship among listeners of classical and opera, allowing them to make judgements on performances based on criteria which would seem baffling to those outside of the cognoscenti. Ironically, rock – a genre which is often seen as being overly concerned with musical prowess and power – can seem weak when seen in this larger context. Even when judging live albums on the more ephemeral qualities of "rawness" or "groove", rock, funk and soul don’t particularly have that much of an edge over jazz, generally speaking.)

So, why are live rock albums second class citizens? Is it because most of the time the live album doesn’t really reflect the punter’s experience of the gig? From albums that are constructed mosaic-like, cherry picked from recordings taken from multiple nights on a tour (or in some cases from entirely different tours) to albums that are over-dubbed mercilessly in the studio to downright fraudulent studio releases with dubbed on applause. (We’ve included some some of these grey area, "fraudulent" releases here, in fact I voted for one – Sex Machine by James Brown – which should probably be seen as having been mainly played live in the studio.)

There are more than a few hardcore fans out there who will tell you that bootlegs are the real document. and that they’re not interested in live albums at all. Producers are aware of the allure of the bootleg and will allow the odd bum note or fumbled drum fill past the edit and on to the final release simply to signify how ‘real’ the album is, how ‘caught in the moment’. But to pick and choose the optimum deployment of stunt mistakes to act as a signifier is no less fake than slapping the applause from The Who’s Live In Leeds over your four track demo.

But despite all this, there are a handful of artists whose live albums are their greatest releases and many more aside who have released astounding concert documents that should be sought out with extreme prejudice. The recent reissue of one of my favourite all time concert LPs, Hawkwind’s The Space Ritual Alive In London And Liverpool by EMI, prompted me to take a straw poll from our writers and soon, with no science, logic or planning I had a list of 40 albums, all of which are phenomenal in one way or another.

The list is unranked and instead of date of release, and the year in brackets is the year (or years) that the material was recorded in. You can also listen to a pretty extensive selection from the list via the Spotify playlist above. This is a list of our favourite albums as we remembered them on a particular day last week and not an attempt to draw up an objective best of list, as these nearly always turn out to be rubbish anyway. That said, please let us know what you would have included, and there’s a handy list of all the titles at the foot of the piece should you want to cut and paste elsewhere.

I’ve discarded live ‘electronic’ albums, mixtapes and bootlegs from this list as they are all being dealt with by other features coming later in the year. I hope this is as much use to you as it has been to me… I’ve already been out and bought albums by Albert Ayler and Sun Ra off the back of it.

John Doran

Contributors: John Doran, Sean Kitching, Julian Marszalek, Charles Ubaghs, Andy Thomas, Kevin McCaighy, Wyndham Wallace, Matt Evans, Charlie Frame, Colm McAuliffe, Stewart Smith, Laurie Tuffrey, Austin Collings, Sophia Deboick, Russell Cuzner, Paul Tucker, Rachel Mann, Emily Bick, Chad Parkhill, Ryan Alexander-Diduck, Pavel Godfrey, Rory Gibb and Luke Turner.

Electric Masada – At The Mountains Of Madness

(Tzadik 2004)

This two CD set, recorded in 2004 in Moscow and Ljubljana, is always the first thing I think of whenever anyone mentions favourite live albums. John Zorn takes the Ornette Coleman inspired ‘radical Jewish music’ of his Masada songbook as a starting point and then nods to Live-Evil era Miles Davis and revisits the heaviness created by his own Naked City group. This combination was always going to be a winning idea. Then there’s the line-up itself. Two incredible drummers in the form of Joey Baron and Kenny Wollesen, with Cyro Baptista on percussion. Trevor Dunn on bass and Marc Ribot on guitar. Jamie Saft on Keyboards and Ikue Mori on laptop, summoning all kinds of sonic precipitation as Zorn’s mercurial sax shrieks, soars and spits electricity throughout. This is gorgeous, rich-sounding music, at times lyrical and beautiful and at others almost brain-meltingly intense and psychedelic. The differences apparent over the two discs, which contain essentially the same tracks, showcase the high-level of directed improvisation going on, to the extent that it’s not immediately apparent that you are listening to the same source material. The two versions of ‘Kedem’ are particular highlights. The CD package itself is also a beautiful thing, decorated with demonic-looking Tibetan Buddhist artwork.

Sean Kitching

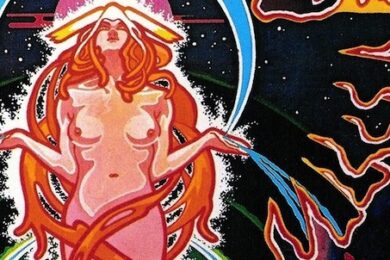

Siouxsie And The Banshees – Nocturne

(Polydor 1983)

Whether it was Bauhaus’ Peter Murphy swathed in the glorious sweeps of Mussorgsky’s ‘Night On Bald Mountain’ whilst advertising Maxell cassettes or Siouxsie And The Banshees electing to open this grand double live album to the strains of the once scandalous The Rite Of Spring by Stravinsky, it looked as if goth was attempting to align itself with classical music’s more dramatic gestures. But if Siouxsie And The Banshees failed to spark the kind of riots that greeted the 1913 premiere of Stravinsky’s experimental piece, the two concerts at the Royal Albert Hall in the dull autumn of 1983 that provided the songs for this live album caused no little excitement among the faithful. For this writer, attending the second concert on October 1, one of the thrills was my first visit to the stunning environs of the Royal Albert Hall. The other was the anticipation of seeing The Cure’s Robert Smith on guitar duties in the wake of John McGeoch’s departure and their recent smash hit, a cover of The Beatles’ ‘Dear Prudence’. Though the order of songs differs wildly from what was actually played across the two nights, Nocturne stands as both a representation of where they were at that point in their career and their status as an incredible live band. Be it Budgie’s precise and muscular rhythms, Steven Severin’s flanged bass, Siouxsie’s commanding presence or Robert Smith’s interpretation of other guitarist’s material, the performance is magnificent and convincing throughout. By cherry picking their finest material, Nocturne was – and still is – a kind of alternate Greatest Hits that acts as a gateway to their kaleidoscopic world.

Julian Marszalek

Neil Diamond – Hot August Night

(MCA 1972)

The bouffant. When perched high on a man’s head, a bouffant can look like a wild profiterole that’s come home to nest for the night. It’s absurd. Neil Diamond sports a mighty bouffant on the cover of his 1972 live double album Hot August Night. It doesn’t just tower above his head, it flows down and around the head of a man occasionally dubbed the Jewish Elvis like a hirsute crown. It’s absurd, but absurdity is not something lost on Neil Diamond the songwriter and performer. The absurdity in question here, though, isn’t the tongue-in-cheek, raised eyebrow commonly tossed about these days, and it’s not the skewered wit of a Randy Newman or Harry Nilsson’s self destructive sort. Diamond is a populist. Unabashedly so. And having first earned a living as a writer in the Brill Building and penning some of the Monkees’ greatest hits, he’s proven himself to be a songwriter and performer who’s never concerned himself with notions of hipness or wrapped himself up in personal mythology. Diamond is a man who writes for the masses. It does means he’s often prone to teetering into gauche schmaltz that no amount of critical re-apprasial could ever hope to salvage. At his best, though, Diamond’s work reflects a sensibility that refuses to whitewash the difficulty and absurdity of existence, nor does it retreat into the elitist spheres of knowing that such awareness often leads to. Diamond has experienced real life’s little absurdities, and he looks for the collective meaning within that experience by sharing as directly and honestly as he knows how… which is through huge, mass appeal pop songs. Admittedly, maintaining a healthy balance between schmaltz and collective joy is a tough one. Which is why Hot August Night is arguably Diamond’s most complete album. It’s certainly the only one that showcases the connective tissue running through his crowd-pleasing showman shtick and the introspective side of the songwriter who wrote ‘Solitary Man’. It’s all gloriously absurd, but what is great pop music if it doesn’t kick back against the everyday, even when it’s clad in double denim and a mighty mound of hair? Diamond gets it. Diamond knows. And it’s on Hot August Night that he shows it best.

Charles Ubaghs

Sun Ra & His Arkestra – Live At Montreux

(Saturn 1976)

When Gilles Peterson recently paid tribute to Claude Nobs, the founder of the Montreux Jazz Festival, there was only one LP to reach for. Recorded live at the Swiss festival in the summer of 1976, Live At Montreux remains one of the most revealing documents of the genius of Sun Ra and his Arkestra, and one of the heaviest live jazz records, period. Originally issued in 1977 on his own Saturn label, with a hand-drawn cover, the LP remained out of print and all but lost until 2003 when it was finally re-issued by the Italian label Universe. And the blast of hearing the classic Arkestra line up (including the horns of Marshall Allen, John Gilmore, and Pat Patrick alongside the space vocals of June Tyson) in full flight has not diminished in the last 10 years. Check the YouTube clip below for the full impact of the creative improvisation and free-form expression at work. A sensory overload from somewhere out there!

Andy Thomas

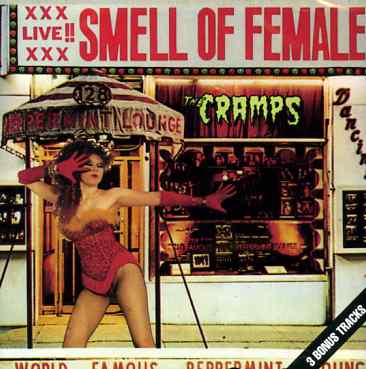

The Cramps – Smell Of Female

(I.R.S. 1983)

Hampered by an enforced two-year recording lay-off thanks to a legal dispute between The Cramps and Miles Copeland’s I.R.S. label, psychobilly’s prime movers became one of the most bootlegged bands in the world. With the quality of numerous illicit live recordings ranging from excellent to dire, the thirst for new material from The Cramps was finally satiated in the form of this live six-track mini-album. Recorded over two nights in February 1983 at New York’s famed Peppermint Lounge, Smell Of Female marks both a return and a farewell of sorts from The Cramps. Opening with the fuzzy onslaught of ‘Thee Most Exalted Potentate Of Love’, this document finds The Cramps moving away from the murky, reverb-drenched madness of its predecessor, Psychedelic Jungle, into much more muscular and musically aggressive territories. Similarly, ‘You Got Good Taste’ and the truly demented ‘Call Of The Wighat’ sees the dynamic of Congo Powers’ crackling fuzz guitar coalescing beautifully with six-string dominatrix Poison Ivy’s twangs and singer Lux Interior’s salacious intentions. Inspired covers of The Bostweed’s theme to Faster, Pussycat! Kill! Kill! and The Count Five’s seminal ‘Psychotic Reaction’ introduced a whole new generation to the respective joys of Russ Meyer’s mondo trash and the first wave of 60s punk rock. Smell Of Female not only marked the end of the two-guitar-no-bass line-up but also of The Cramps’ near-unhealthy interest in schlock-horror B-movies for lyrical inspiration, as they began turning their attentions to double and, more often than not, single entendres. Though The Cramps went on to rock for another couple of decades, they never quite rolled like this again.

Julian Marszalek

The Velvet Underground – 1969: The Velvet Underground Live with Lou Reed

(Mercury 1969)

Recorded in Texas and California in late 1969 and finally released in 1974, this double live album from The Velvet Underground is one packed with a number of delicious ironies. Indeed, around eight years after its release and at the height of post-punk and the chart-worrying sheen of new pop, The Velvet Underground was the name to drop, with this album often held up as the one to go to. Though regularly cited as one of the most influential bands ever, these recordings are of the post-John Cale line-up, and rather than finding them weaving the sonic tapestries that had seen them make their name as part of Andy Warhol’s Exploding Plastic Inevitable revue, this album reveals them as a colossal rock & roll monster. The interplay between Reed and fellow guitarist Sterling Morrison is a joy to hear while the rhythm section of drummer of Maureen Tucker and Doug Yule is utterly watertight across the album’s four sides of vinyl. Thanks in part to the rudimentary recording set-up, the lack of an audience mic gives the impression that The Velvet Underground constantly played to a succession of empty venues and so added to the myth that the band was universally reviled. In truth, the band had picked up a sizeable live following which allowed them to stay on the road for the best part of 1969. The album also contains some radically different and, in some cases, superior versions of officially recorded songs. ‘Rock And Roll’ is a more elementary reading of the version that appeared on Loaded a year later, while the hypnotic and circular rendition of ‘What Goes On’ remains the definitive account. Like all the best live albums, it simultaneously gives long-term observers a different side of the artists concerned, as well as acting as a welcoming gateway for the curious novice.

Julian Marszalek

Ramones – It’s Alive!

(Sire 1977)

"WUNCHEWFREEFOR!" Such is the visceral power of the live recording contained herein that, as was the case with your humble scribe, to hear this before the studio LPs that it draws deeply from – Ramones, Leave Home and Rocket To Russia – means that the source material can feel a little… well, light, upon first encounter. Captured live at the Rainbow Theatre in London on New Year’s Eve 1977, the album’s 28 songs are spewed out at a breathlessly frantic pace in just under an hour. Making a valid claim for being one of the greatest live albums of all time, It’s Alive! is an incredible testament to the sheer joy and energy of undiluted rock and roll; snotty, deviant, brash and as much fun as one can have without resorting to illegal or morally questionable means, this is an album that demands to be heard at full volume. Moreover, it is one of those rare examples where a live album actually transcends its studio origins.

Julian Marszalek

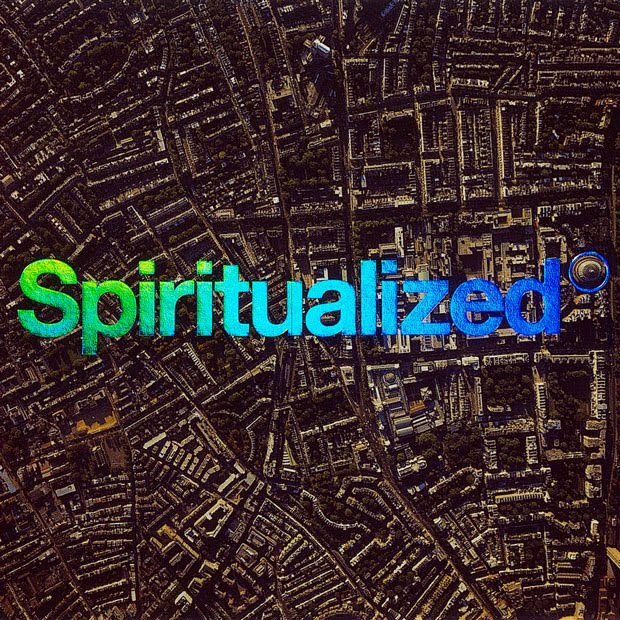

Spiritualized – Royal Albert Hall October 10 1997

(Dedicated 1997)

Can a live album ever improve upon the albums that it draws from? Spiritualized’s second live album (the first, Fucked Up Inside was only available via mail order) makes the doubly bold claim of making good on that premise as well as attempting to gain pole position in the pecking order of their ever-increasing yet diminishing back catalogue. Woven as a continuous piece linked by a dreamy drone that runs like a thread throughout, this live performance in the wake of the peerless Ladies & Gentlemen We Are Floating In Space album sees Jason Pierce marshalling his band, members of the London Community Gospel Choir, a string quartet and a horn section to create a lasting and continually satisfying statement. With the influences of soul, gospel and psychedelia reaching their peak, this live recording works beautifully as a symphony with each track becoming a movement within it. Painstakingly crafted and executed with emotion, care and controlled chaos, Royal Albert Hall October 10 1997 is a testament to ambition and a far-reaching sonic vision, and proves conclusively that the live experience can, when played this well, leave its origins back on Earth.

Julian Marszalek

Judas Priest – Unleashed In The East

(Columbia 1979)

This extraordinary metal monument from 1979 captures Judas Priest at the apex of their early aggressiveness, setting the seal on their first flush of acclaim with a blistering ‘live’ set captured in an appropriately exotic setting. What’s clear is that the album was conceived less as a raw document of the group’s live prowess but as a purposefully constructed statement by a group on the cusp of global super-stardom. From the opening salvo of ‘Exciter’ to the climactic ferocity of ‘Tyrant’, Unleashed in the East is a consummate demonstration of every aspect of the Priest live agenda, the subtlety and savagery of their already impressive back catalogue skilfully executed by musicians galvanised by their success. Rob Halford is on immaculate form throughout, delivering a lifetime best vocal on the definitive version of their signature epic ‘Victim Of Changes’. More importantly, the photos adorning the front and back sleeve enshrined forever Priest’s visual aesthetic as the quintessential oufit for any self-respecting metal warrior. The studio amendments do nothing to detract from the album’s mythic power; these gilded edges merely enhance its aura as a symbol of the group’s ascent to metal’s high table.

Kevin McCaighy

Fela Ransome-Kuti And The Africa ’70 With Ginger Baker – Live!

(Regal Zonophone 1971)

Even though Cream split in 1968, it would take Eric Clapton until 1976 to really nail his colours to the mast about how he felt about people of colour when he wasn’t getting rich and famous off the back of strip mining their music. The blues guitarist launched into a hateful rant onstage at the Birmingham Odeon urging his fans to vote for Enoch ‘Rivers Of Blood’ Powell, drunkenly shouting: "Get the foreigners out, get the coons out, get the wogs out." The very same year, former Cream drummer Ginger Baker was enjoying his seventh year living in Lagos, Nigeria, and we know this because he recorded a particularly blazing drum duel with Tony Allen, Fela Kuti’s 1970s sticksman and Afrobeat co-originator. The 16 minute rhythm track has been tacked onto the end of several CD reissues of this must-have live album as a fifth track – which is weird because the actual concert happened some six years earlier. But still… just how good do you want a live album to actually be? The first two tracks featuring ‘just’ Fela and backing group Africa ’70, ‘Let’s Start’ and ‘Black Man’s Cry’ are phenomenal, but then ‘Ye Ye De Smell’ and ‘Egbi Mi O (Carry Me I Want To Die)’ take proceedings stratospheric when Baker is introduced into the line-up. Allen and Baker – who remain close friends to this day – are clearly in awe of each other’s talents, and the interplay is a joy to listen to. That white blues rock musicians leant on and profited from black talent in a deeply unpleasant way in the 1960s is an uncontroversial fact; but for the most part it’s probably how they handled themselves afterwards and how respectful they were of black culture in general that they should perhaps be judged against.

John Doran

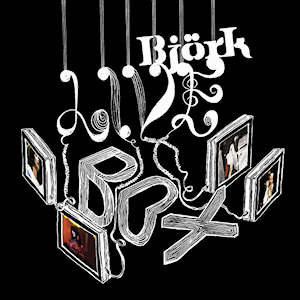

Björk – Live Box

(One Little Indian 2003)

Until I sat in the stalls of the Royal Opera House on December 7, 2001 – just short of 12 weeks after my business partner’s suicide – I had no idea how much Björk’s Vespertine album meant to me. But when the opening musical chimes of ‘Frosti’ first started I broke down crying, and I continued to weep for the duration of the show, hiding in a corner of the bar through the interval as my shoulders refused to give up shaking. The record, I slowly realised, had been playing when I received news of his death. Every note, every quiver in Björk’s voice, took me back to that moment, one in which most of my professional dreams combusted in the time it took to deliver a single short sentence. There’s a DVD of that performance, but I’ve never been able to watch it. Instead I turn to the Vespertine live collection [CD four of Live Box], which is somehow one step removed from that dreadful night of grief. The goosebumps still rise, sorrow still seeps into the sounds I hear, but the sheer magic and beauty of Björk’s otherworldly, innocent music – given extra human warmth by its live context – nowadays comforts me. I still fight back tears when I hear that Inuit choir, though, especially on ‘It’s Not Up To You’: "I can decide what I give/ But it’s not up to me what I get given."

Wyndham Wallace

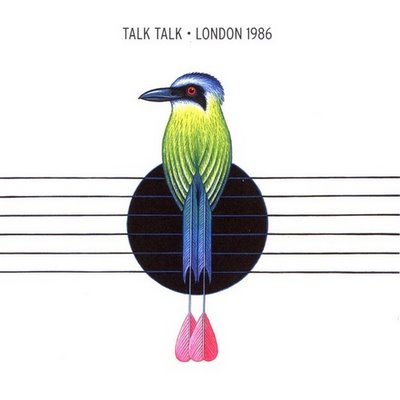

Talk Talk – London 1986

(Pond Life 1986)

The legend of Talk Talk is frequently advanced by their refusal to perform their final two albums live. London 1986 reveals that this was an even greater loss to their fans than they might have imagined: the pristine veneer of their early material is given an organic superiority on stage, with the sluggish tempos of ‘Renee’ and ‘Does Caroline Know?’ emphasising their central melancholy, with Mark Hollis’ voice never more weary. ‘It’s My Life’ and ‘Such A Shame’, on the other hand, never sounded more effervescent. Tracks from The Colour Of Spring also benefit from the band’s immaculate tightness: ‘Life’s What You Make It’ and ‘Living In Another World’ overflow with ferocious energy, and the Hammond Organ on ‘Give It Up’ emotes with such tremulous potency that it seems to be as alive as the musicians surrounding it. The distant sound of crowd participation may seem at odds with the records they would soon make, but there’s something uplifting in the knowledge that music like this could fill the Hammersmith Apollo for two consecutive nights. Though it lacks the expansive treatments on display on their Live At Montreux DVD, London 1986 – which also sadly fails to contain everything they performed that night – defies the belief that Talk Talk were only interesting once they’d burrowed deep into the avant-garde.

Wyndham Wallace

Donny Hathaway – Live

(Atlantic 1972)

It’s unlikely any party we ever attend will be as great as that documented on these recordings from two shows – one in Hollywood, one in Greenwich Village – from 1972. Separating the jubilant quality of the performances from his apparent suicide seven years later is hard, of course, and the opening track, a passionate, uplifting cover of Marvin Gaye’s ‘What’s Going On’ – still only a year old then – highlighted there was always a dark side to this too often overlooked soul man. You’d be hard pushed to find anything more thrilling than his twelve minute version of ‘The Ghetto’, however: Hathaway’s piano solo is electrifying, the rolling bass line one of the simplest but most effective grooves ever laid down, and the extended breakdown at its centre justifiably elicits the kind of response normally restricted to gospel services. Hathaway was always a superb interpreter of other people’s material, and his version of Carole King’s ‘You’ve Got A Friend’ is spirited, stirringly tender and touchingly redemptive, even if his take on ‘Jealous Guy’ is a little throwaway in comparison. But the final, near 14 minute version of his own ‘Voices Inside (Everything Is Everything)’ – the title track of his debut album two years earlier – more than compensates. No wonder the crowd can be heard yelling for more as the record fades. In a perfect world, this album would bring the dead back to life.

Wyndham Wallace

Cardiacs – All That Glitters Is A Mares Nest

(Alphabet Business Concern 1990)

June 1990. Napalm Death are recording a live video at a Salisbury church-cum-arts centre. Sensing a bulk-buy bargain, their manager sorts an afternoon gig for another band in the same venue. And the greatest live album ever made barely available to the public is captured between Going For Gold and Countdown. Mare’s Nest is wondrous for several reasons. Firstly, it takes Cardiacs’ kaleidoscope-prog and ultra-pop impossibility and gives it a fiery hoof up the colon. From the bruising, nigh-industrial intro through the perilous frenzy of ‘To Go Off And Things’ to the sustained climax of unlikely minor hit ‘Is This The Life?’, this is delirious, potent stuff, the sound of wild ideas obsessively woven from flesh and wire and moments. Second: Tim Smith is a captivating host. Absurd, charming, malevolent and juvenile, his betwixt-tune chat exists at the intersection of Spike Milligan, George from Rainbow and Dennis Hopper. Who else could bellow "KISS THE BIG UGLY SHARK!" with such glorious conviction? Third: live-album crowd noise usually resembles a dead dog dragged through autumn leaves, but here the audience are central, individuals, their boisterous community palpable. Fourth: self-haruspicy. The footage reveals future Cardiac Jon Poole, then but a fan, giving serious hand jive down the front. Finally: this was my first Cardiacs album. The deepest loves are sneaky, grow exponentially and just won’t leave.

Matt Evans

Depeche Mode – 101

(Mute 1988)

If some live albums leave you with a "you had to be there" feeling, 101 pretty much immerses the listener in you-are-there hysteria from the start as ‘Pimpf’ fades up in a booming cascade while huge waves of screaming crash down on top of it all. Credit for 101‘s success llies not just with the band’s tour-concluding performance in the Rose Bowl in Los Angeles, although they do put on a great show. However the real secret here is Alan Moulder – his engineering of the tapes, one of his earliest credits, made the full wallop of Depeche’s theatrical electronics pound out more forcefully than most LA hair metal bands of the time could ever hope to achieve, while making even the quiet songs like ‘The Things You Said’ sound moodily powerful.

Ned Raggett

Fields Of The Nephilim – Earth Inferno

(Beggars Banquet 1990)

By the time of the 1990 shows that were recorded both for video and live release, Fields Of The Nephilim had transcended their Sisters of Mercy-meets-Morricone start into something moodier on record, a queasily, dramatically bleak and psychedelic series of songs that ended up being more than a little secret influence on plenty of orchestral and dark metal to come. But Earth Inferno ended up producing the definitive versions of nearly everything they’d done from the beginning, the compelling textures driven forward by a monstrous rhythm and riff combination for the ages that they never quite seemed to get right in studio. When ‘Last Exit for the Lost’ slowly transformed from tense atmospherics to a blasting overdrive, Carl McCoy sounding like he was being cast into an abyss and then crushed by an avalanche, it’s a wonder anybody left those concerts under their own power.

Ned Raggett

Talking Heads – Stop Making Sense

(EMI 1983)

"Hi, I’ve got a tape I wanna play you". And so starts one of the most ambitious, conceptual and divisive live documents of the 1980s. By 1983 Talking Heads’ transformation from scratchy post-punk four-piece to Eno-helmed art-funk superstars was complete. Their previous two albums had been very much products of the studio – spliced, layered and dubbed to the point where even the band members themselves felt in the dark as to the songs’ structures during the process. And yet even in this incarnation David Byrne’s troupe remained very much a live band. The husband-and-wife team of Tina Weymouth and Chris Frantz had become impeccably honed to their crafts, locking grooves and playing as a singular rhythmic superforce. Byrne himself had blossomed from a reticent murmurer to a bug-eyed, all-yelping, all-dancing stage performer. Meanwhile, Jerry Harrison worked as the essential glue that bound the band together. Perhaps capitalising on these abilities, Byrne brought in the help of a number of new musicians, expanding his Heads line-up into a full-blown live revue. As new members are introduced to the stage for each consecutive song, Stop Making Sense tells the story of Talking Heads, beginning with Byrne singing acoustically the first song he wrote for the band, ‘Psycho Killer’, ushering-in his band mates one by one and then adding backing singers, percussionists, members of Funkadelic and Parliament, until it’s just one big meticulously-orchestrated onstage meltdown. While the music has come to be eclipsed by the celebrated film documentary of the show, taken on its own terms, Stop Making Sense is still a wonder. Many of the performances are sharper, nimbler and all-round better than their studio counterparts, particularly the songs from the underrated Speaking In Tongues album. Tracks like ‘Making Flippy Floppy’ and ‘Slippery People’ truly come into their own here, while the live version of ‘Once In A Lifetime’ is also infinitely more powerful than its studio version, soon coming to outgrow it in popularity. Stop Making Sense as a film is a remarkable conceptual work, but as an album it’s also the perfect primer for anyone looking for an introduction to the band.

Charlie Frame

Curtis Mayfield – Curtis/Live!

(Curtom 1971)

During the 1960s, via his group The Impressions, Curtis Mayfield helped soundtrack the civil rights movement and also assisted in laying the foundations of funk, but he struck out on his own just as the 1970s started. As well as starting the Curtom record label, he gave his solo material a harder edge that was more concerned with clear eyed reportage than utopian dreaming. He’d literally only just got his debut Curtis out of the way when he recorded his first live album, and it shows, as there are only a few of his own solo songs on offer and he turns in a set studded with generous versions of Impressions songs such as ‘People Get Ready’ and interesting covers. One of the many stand-out tracks on this double is what he says some might find "inappropriate" for the underground, a version of The Carpenters’ ‘We’ve Only Just Begun’ but removed from its romantic context and remade as a political statement of intent for the decade ahead. What really impresses here is the sheer intimacy of the recording. It’s the work of a four piece during one teeth cutting residency at the Bitter End nightclub in New York in January 1971, and Curtis’ in between song "raps", the frequent exhortations (not to mention backing vocals) from the audience and ambient noise place you right in the middle of a perfect set by a man who is singing with an angel’s voice, an artist’s eye, a lover’s heart and a radical’s mind.

John Doran

Tim Buckley – Dream Letter: Live In London

(Enigma 1968)

By 1968, Tim Buckley was approaching the apotheosis of his creative ingenuity, ushering in a period which would result in three remarkable, often wildly differing, releases, Happy Sad, Lorca and Blue Afternoon. The primary influences on this ravishing, rambling stream of sonic extemporising? Well, if the stage patter punctuating Dream Letter is anything to go by, it was all down to the paucity of carnivals in New York city and the considerable influence of three hundred grams of shredded meat. Buckley’s set, recorded in October 1968 on his second (the liner notes erroneously state it was his first) UK tour, showcases the 21-year old’s increasing fondness for improvisation and glorious unpredictability. The addition of Danny Thompson on double bass to the stripped-down sound further affords Buckley the space to test the limits of his octaves at altitude; the two-hour set, comprising a number of songs which never made it on to his LPs, effortlessly flits between originals, show tunes and even a Supremes cover, and shimmers with a transcendent melancholy, sensuality and quite remarkable freedom of expression. ‘Dream Letter’, glimmering in equipoise between the ‘curly haired mountain’ folk singer of yore and the horny-as-hell devil of priapic funk evinced by 1972’s Greetings From L.A., showcases a singer at the absolute apex of his power, and still succeeds in inducing a shiver of primal, sensory bliss.

Colm McAuliffe

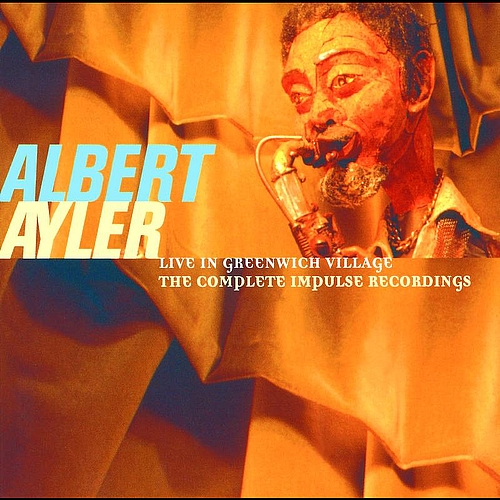

Albert Ayler – Live In Greenwich Village – The Complete Impulse Recordings

(Impulse! 1965-1967)

There are several excellent Albert Ayler live recordings out there, not least the recently issued Stockholm, Berlin 1966, but the complete Greenwich is the motherlode: a desert island worthy two-disc set documenting the inspirational free jazz saxophonist’s performances in the Village between 1965 and 1967. These capture Ayler in his prime, drawing inspiration from American tradition, while fearlessly pushing his music out into the unknown. On these discs you’ll hear parade tunes, old world psalms and folk dances, their forms exploded in an ecstatic march to freedom. ‘Holy Ghost’ bursts out of the pulpit with Albert and his brother Donald speaking in tongues, the latter’s trumpet sputtering while Albert’s tenor burns. Sunny Murray hammers at his snare like Hephaestus in the forge, while bassist Lewis Worrell responds with tectonic arco groans. It’s an extraordinary opener, fearsomely avant-garde yet full of uncanny resonances. ‘Truth Is Marching In’ begins as a New Orleans funeral lament, the Aylers holding the stately melody while Beaver Harris’s drums detonate around them. It then alternates between an uplifting marching band reveille and hair-raising improvised passages featuring Albert’s wailing tenor, Donald’s urgent trumpet squalls and the careening double-stops of violinist Michel Sampson: a thrilling embodiment of Ayler’s radical folk vision. The playing can get plenty dissonant and wild, but there are also moments of rare beauty and grace. The hymnal ‘Our Prayer’ and Donald’s divine ‘Angels’, the latter performed with voluptuous piano accompaniment from Call Cobbs Jr, are deeply moving. Even in these most gorgeous of tunes, Ayler’s saxophone retains its physicality, his gospelised tone reaching for the sublime. This is astonishing music, a testament of soul and fire.

Stewart Smith

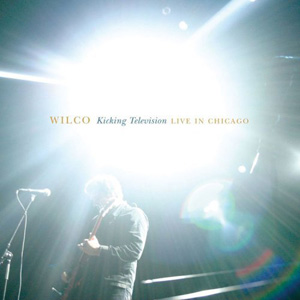

Wilco – Kicking Television: Live In Chicago

(Nonesuch 2005)

Recorded over a four-night residency at the Vic Theater in their hometown of Chicago, Kicking Television marked Wilco’s first release with Nels Cline, a freakishly virtuoso guitarist whose inclusion effected a transformative moment for the band, first documented here. Across the tracks, cherry picked from almost every one of the band’s albums, Cline’s guitar has a semi-liquid texture, transcending what should be possible with a battered ’59 Jazzmaster: encased in the hails of feedback on ‘Handshake Drugs’s coda or the spasms of pure euphoria on ‘Shot In The Arm’, they’re the sonic equal of the coruscating light-glare on the album cover. Grounding everything, meanwhile, is Tweedy. His introspective, imagistic lyrics are what had always touched Wilco with genius, a fact never before as transparent as it is here: amid the rhythmic cataclysm halfway through ‘Via Chicago’, there he is, intoning the beautiful obliquity of fragments like "crush of veils and starlight" in a resolute Midwestern burr. On opener ‘Misunderstood’, once Tweedy has navigated the jaded afternoons of youth, maybe his youth, dappled with apathy and withdrawal, the band crash in, stopping at the line "I’d like to thank you all for nothing", and cycling over it as Tweedy screams that last word 36 times. If their studio LP immediately prior to this, A Ghost Is Born, was Tweedy’s reflective catharsis of post-rehab, Kicking Television was him staring the black dog straight in the eye and shouting it down.

Laurie Tuffrey

Neil Young & Crazy Horse – Live Rust

(Reprise 1979)

Something of the overlooked younger sibling, Live Rust was recorded on the same half acoustic/half electric 1978 Rust Never Sleeps tour as the film and album of that same name, and only released four months later. But where Rust Never Sleeps is a celebrated yet occasionally underwhelming hybrid of live recordings and studio overdubs, Live Rust feels like the real deal. The first half’s acoustic songs almost all best their studio counterparts. ‘Comes A Time’ becomes a clear-eyed anthem, with the aphoristic poignancy of the chorus worn openly, while for ‘After The Goldrush’ Young switches to electric piano, providing the album’s most luminescent moment: the French horn gets replaced by a harmonica, with the air around Young audibly riven by the solo’s heartbreaking cadences. The ‘concept’ for the tour featured roadies dressed as the Jawa from Star Wars blasting out sound clips from the Woodstock concert film, a remnant of which turns up before ‘The Needle And The Damage Done’, imprinting the album with the kind of brilliant (and ridiculous) excess that only Young could bring to the table. It’s there as well in the Crazy Horse songs, thrashed at with an almost punk-like febrility, yet simultaneously stretching out to become vast, hulking behemoths. One of them, ‘Hey Hey, My My (Into The Black)’, with its three chord sucker punch sounding like a lightning strike playing out within Young’s vastly-oversized amp casings, reflects the album as a whole, primal, howling and gloriously laced with ragged excess.

Laurie Tuffrey

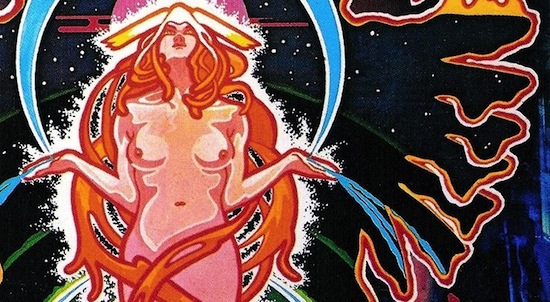

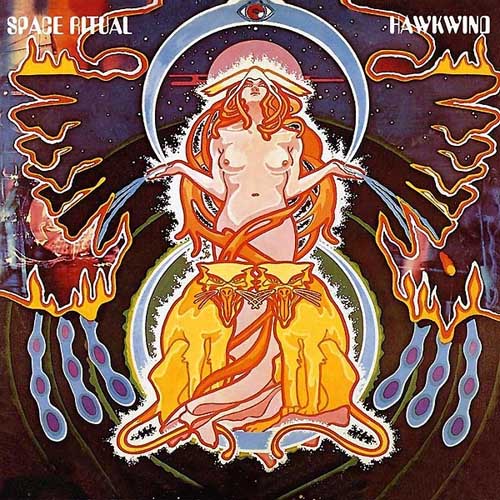

Hawkwind – The Space Ritual Alive In Liverpool And London

(United Artists 1972)

I interviewed Luke Haines for Noisey last year and, naturally, talk turned to Hawkwind, or as he called them the band that Pink Floyd could have been, if they’d been less middle class and shit. (At least I think that’s what he said, it was a very odd morning.) I also asked him what people should do to remember the recently departed Huw Lloyd-Langton and he replied simply, "Levitate" in reference to the band’s excellent 1980 album Levitation. After you have done this you could celebrate your return to Terra Firma with a blast of this astounding 1973 live set recorded in London and Liverpool. Lloyd-Langton wasn’t part of the line-up at this point, having departed to play guitar for Leo Sayer, but regardless this, to many, is the ultimate space rock artefact: bonkers Bob Calvert poetry, whirring hyperdrive oscillators, interstellar dust cloud flute solos, a performance piece written by sci-fi author Michael Moorcock [‘Sonic Attack’], a starship hull blistering performance of ‘Space Is Deep’ and the unstoppable cider, amphetamine and motor oil chug of ‘Orgone Accumulator’, all linked into a preposterous tale of astronauts traversing the galaxy in hypersleep, and encased in fantastic faux art deco packaging, based on Hawkwind’s painted Amazonian dancer Stacia, pictured with plasma flowing from her fingertips flanked by giant firey eagles and what appear to be golden space leopards.

John Doran

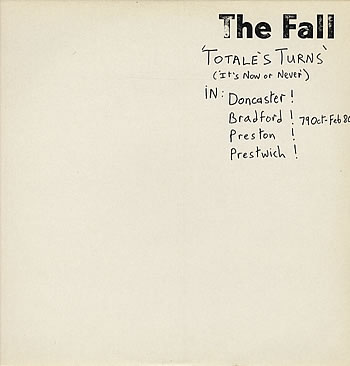

The Fall – Totale’s Turns (It’s Now Or Never)

(Rough Trade 1979-1980)

Quoting Samuel Beckett, this is The Fall’s "mutilated statement of an identification". A fiercely ordinary live document that may have been recorded inside a just-drunk can of Skol. It’s also the sound of a V-sign; of Tom Courtenay in The Loneliness Of The Long Distance Runner, David Essex in That’ll Be The Day, Richard Allen book covers, and a slew of past and future young chip-skinned, feral-chested rebels without a coin, at war with the obvious crap, and gifted with great negative potential. There’s an element of The Stooges (vinyl stand-off) Metallic K.O. in there as well. Only the audience is not a crowd of hostile bikers, but hard-to-please, art-threatened proles fogged in lung-achers, and soaked in Bass, out for a "good night" in working mens clubs in Bradford and Preston. Barricaded within brick, fighting their corner, the group are by turns Gene Vincent’s Blue Caps, Can and something brilliant and barking and never heard before – or since. And there at the front, baiting the flummoxed audiences with his customary sarky bite, stands Mark E Smith, channelling the antagonistic spirit of Lenny Bruce via Granada’s Wheeltappers and Shunters – "The difference between you and us is that we have brains…" – skin like a rhino, in his element, at the start of a special career that continues to enthral and mesmerise.

Austin Collings

Dr. Feelgood – Stupidity

(United Artists 1975)

As a document of the live sound of a band who predominantly thrived live, Dr Feelgood’s Stupidity was, unsurprisingly, their only number one album. Recorded partly on home soil at Southend-on-Sea’s Kursaal, the album captured their raw R&B energy in a way their studio material had distinctly failed to. Frontman Lee Brilleaux said of Stupidity that it "was the culmination of the revolution against the stack heel and platform shoe brigade… We said bollocks to all that, this is how a live band really goes to work." Indeed, by 1976 glam was over and the point of decay was tipping over into renewal. Writer and ex-Essex pub rocker Will Birch’s contention, later vividly taken up in Julien Temple’s Oil City Confidential, that the band were essentially proto-punk, is borne out by Stupidity, where their grit is writ large. For those of us who grew up in south east Essex in the band’s late-Brilleaux years, the Feelgoods’ earthiness was underscored by them remaining a very ‘local’ band, despite pan-European success. It didn’t matter that they were of our parents’ generation – in Wilko Johnson’s words, this was simply music "for people who want to have a good time" – and Stupidity remains evidence of the universal appeal of four blokes pounding away on HP instruments and raising a riot.

Sophia Deboick

Coil – …And The Ambulance Died In His Arms

(Threshold House 2003)

Coil avoided the crowd-pleasing roll-out of ‘greatest hits’ to offer sets of evolving, embryonic songs, confirming their progressive creativity. But these highly-anticipated yet unpredictable experiences could often race past, leaving you wishing for more than a residual sense of what went down musically. On the long journey home from the Autechre-curated ATP Festival in 2003, my mind surged with memories of Coil’s most fragile, "quiet set". In the following days droplets of its details helplessly evaporated, leaving me primed but lacking the catalysts essential to become more fluent in their intoxicating new language. This album provided the necessary chemical reaction to rapidly re-hydrate the drying stock of precious, sensual memories the show initially bestowed. Once more their gentle noir-ish refrains and hypnotic pulses, scorched by spasmodic electronic shards and cooled by a stirring marimba, carried Jhonn Balance’s mesmeric mantras and fervent banter to touch on the mental health issues that influenced his unique praxis. And yet, as the first Coil release to follow his tragic death at the end of 2004, the performance is now forever imbued with emotions not present on stage. Since then it has become perhaps both the rawest and most accessible evidence of Coil’s continuing unworldly affect.

Russell Cuzner

Sepultura – Under A Pale Grey Sky

(Roadrunner 1996)

When Sepultura departed the Brixton Academy stage on December 16, 1996, they trooped toward an almighty dressing room row that led to frontman Max Cavalera quitting the band he had founded as a fifteen year old. After the split the band soldiered on, while Cavalera launched Soulfly – his Sepultura for the nu-metal generation. For many fans though, that night marked the final worthwhile chapter in the band’s history. Under A Pale Grey Sky may have been released against the band’s will – Roadrunner dropped Sepultura shortly before releasing the album in 2002 – nevertheless it catches the band at the peak of their ascent from corpse-painted death-metal teens to one of the most important metal bands of the 1990s. With their concrete-shod riffs bolstered by additional percussion and Amazonian field recordings, the band’s 28-song set covered everything from 1985’s Necromancer to the blunt-edged material from Roots. Combining fierce social commentary, a love of 80s US hardcore and a uniquely percussive approach to metal that reflected a pride in their Brazilian heritage, Sepultura’s music could rarely be described as nuanced, but live it displayed more heart than the majority of their contemporaries could ever dream of mustering in their own shows. As the set draws to a close with a raucous version of Motörhead’s ‘Orgasmatron’, you can’t help but wonder, despite the band’s untimely split: could there really have been a better finale than this?

Paul Tucker

James Brown – Sex Machine

(King 1969-1970)

More than any other 20th century performer, James Brown owned the format of the live album. Even the whitest, most rockist of music magazines will always include Soul Brother Number One’s Live At The Apollo (1963) (alongside their other token black pick, Marvin Gaye’s What’s Going On?) in their lists of the best albums ever recorded. And while …Apollo is a fine, fine soul album, it simply lacks the militant, explosive power of Mr Super Bad in 1970, given that he had instigated a funk coup across America in the intervening years. It’s certainly an act of inverse racism that sees the far superior Gaye album Let’s Get It On overlooked in favour of the ‘serious’ and ‘political’ What’s Going On? (it’s almost like these clowns haven’t heard Curtis Mayfield’s magnificent post-Vietnam album, Back In The World). Is it the same reasoning that stops critics from favouring Sex Machine or Love, Power, Peace: Live At The Olympia Paris 1971? Are these albums are simply too damn rampant for ‘serious’ critics to take seriously? It could be, because whereas Apollo is bright, romantic and playful, Sex Machine, recorded on Mr Dynamite’s home turf of Augusta, Ga, is dirty, torrid and sweat slicked. Never has the olfactory etymology of funk been easier to sniff out on a live recording. This is certainly a live document of the best backing band Brown would ever have, and one that only lasted for a year. The J.B.s at this point included the funky drummer Mr Clyde Stubblefield, Brother Johnny Griggs on congas, time-served side-man Bobby Byrd, a teenage Bootsy on bass, a twenty-something Catfish on guitar, Maceo on tenor sax, Mr Fred Wesley on trombone and Ms Marva Whitney (R.I.P.) on backing vocals. Leave it to the geeks to argue about whether this album is actually live or studio, and just revel in rhythms produced by the unstoppable machinery that was James Brown.

John Doran

Sunn O))) – Dømkirke

(Southern Lord 2007)

Praise be to the enlightened clergy of Bergen, who permitted Sunn O))) to play a gig at the city’s cathedral, despite their association (via vocalist Attila Csihar) with the church burning antics of the Norwegian black metal scene. Indeed, Dømkirke in many ways is a useful tool for explaining Sunn O))) to those who quake before the robes and noise and mutter fearfully, ‘but are they Satanists?’. It demonstrates that their attitude to religion is a thoughtful one, and also shows their mastery of different tones, sound, and sense of space in music. ‘Why Dost Thou Hide Thyself In Clouds’ begins with a long drone through the church pipes, as if the organist had croaked mid-‘Thine Be The Glory’, before Csihar’s vocals lurk around the lingering note. To combine the organ, riffs and vocal as they do in ”Clouds’ and ‘Cannon’ is surely a difficult task, but it’s achieved to great effect throughout. Interestingly, where lesser live albums are retrogressive ‘play the hits’ meanders through catalogue, Stephen O’Malley later told The Quietus that Dømkirke had a profound effect on Monoliths & Dimensions, the album that remains an artistic high-point in early 21st century music.

Luke Turner

Miles Davis – Agharta

(Columbia, 1975)

I’m not going to pretend I’m an expert in the work of Miles Davis. Like most people, I only own a few of what most consider key recordings (Kind Of Blue, In A Silent Way, Bitches Brew, On The Corner, and a scattering more), so I’m probably not particularly qualified to comment on Agharta‘s exact place in the canon of his work. But this is the album of Miles’ that I find myself returning to most frequently, simply because it’s one of the most electrifying and psychedelic live recordings I’ve ever spent time with. 33-minute opener ‘Predule’ is my favourite thing here: a swirling vortex of heavily effected guitars and drums whose cyclical motion seems to stop time entirely, creating an extended state of blissful rhythmic freefall above which Davis and saxophonist Sonny Fortune trade increasingly frantic solos. Eight minutes through, Fortune’s sax screams upwards through the mix with enough power to bring the musicians around him to a juddering halt, cracking open a rift in time for a delirious and tantalising few seconds before the band crash in once again at what feels like double the force. Davis took an extended break from music after the two-part show during which this album and its sister LP Pangaea were recorded, as a result of mounting exhaustion and ill health. But even aside from his deteriorating physical condition, given the amount of energy he pours into Agharta – both into his own playing and his implicit guiding presence as band leader – it hardly seems surprising that he was utterly knackered afterwards. Rory Gibb

Throbbing Gristle – Heathen Earth

(Industrial Records 1980)

As far as these ears are concerned, a good live album ought to offer something substantially different from a band’s existing recorded output. No matter how dynamic the performance, I generally find it tough to be excited by a straightforward recording of well-honed songs, played verbatim. Heathen Earth represents the opposite of that approach, and thus is about as good as it gets for me, live album-wise: an improvised hour-long set that chewed up and spat out fragments of TG’s back catalogue in mutant noise/dub/jazz forms, played in front of an invited audience of 20 or so in their studio in Martello Street, and recorded by an associate of the group with no prior experience as a sound engineer (just to add an extra randomising factor to proceedings). There’s a controlled fury to Heathen Earth, a feeling of deliberation, purposefulness and restraint: the group repeatedly alight upon and explore single ideas – musical or lyrical – over long periods of time. As a result it’s the more thrilling when they occasionally do flare into full force: see early highlight ‘The Old Man Smiles’, when a battery acid-soaked scribble of guitar tears upward through the mix, rough, ragged and dry as the desert sun. Another late peak, ‘Don’t Do As You’re Told, Do As You Think’ bristles and blossoms into a driving, darkly funky slice of undead disco, scarred by aggressively dubbed-out blasts of cornet from Cosey Fanni Tutti. Admittedly the studio setting lacked the confounding factors – belligerent audience members, for one – that reportedly added a more chaotic and cantankerous edge to TG’s ‘proper’ live shows, but then perhaps that’s one reason why Heathen Earth feels so subtle and strange. Either way, it sums up the root of TG’s appeal for me: raw, sinister and caustic, restlessly sonically exploratory, and equally capable of moments of great patience and contemplation. Rory Gibb

Moritz Von Oswald Trio – Live In New York

(Honest Jon’s, 2010)

The list of musicians playing on Live In New York ought to quicken the pulse of most techno heads: bandleader Moritz Von Oswald, Max Loderbauer, Sasu ‘Vladislav Delay’ Ripatti, Carl Craig and Francois Kevorkian, all performing together onstage – how could the results be anything other than astounding? But it still does little to prepare you for how it actually sounds. Von Oswald’s Trio have come closer than most to matching Underground Resistance’s famous notion of techno as ‘hi-tech jazz’ – this performance, and others by the band from around the same time, was largely improvised, and here each musician plays with an impulsive, almost childlike freedom, sending modular synth squeals and bleeps (think early Doctor Who radiophonics) wheeling wildly through the mix, periodically drowned out by huge, billowing melodies that explode outward in slo-mo and dissipate like supernovae. But it’s ultimately all about the rhythms that propel everything along – the performance’s core pulse and clattering metal percussion hint towards club techno’s breakneck momentum, and during the times when everything crescendos all at once, it’s practically impossible to resist the temptation to whoop with excitement. Which is something Francois K, when mixing and mastering the recording afterwards, was clearly aware of: at those crucial moments he turns up the volume of the crowd, pushing their ecstatic response to the fore and providing a timely – and thrilling – reminder that this intuitive and adventurous music is all unfolding, spontaneously, in real-time.

Rory Gibb

Arab Strap – Mad For Sadness

(Chemikal Underground 1999)

By the late-90s, my record collection was in a bit of a pickle. The interesting end of Britpop that had defined my teenage years had given up music in favour of crack and heroin, and what I was hearing its stead – shabby indie rock from America, post-Radiohead bleating and laddy grunting over here – felt devoid of sex or romance. Thankfully, two pissed bastards came from Scotland, to my rescue, like knights in shining lager sweats. Debut Arab Strap album The Week Never Starts Round Here had passed me by, too lo-fi, but Mad For Sadness, acquired via a cardboard sleeve promo CD, had me hooked. This was sex and romance, alright, in all its regret, guilt and waking-in-the-wet-patch awkward truths. For a pair whose pre-gig thirst was the stuff of legend, it captures a remarkably focused performance, the songs of Philophobia rendered dolorous and immense by Malcolm Middleton’s booming guitar, which is not a million miles from what Mogwai were up to at the time. The contrast between this and the more minimal interludes give Aidan Moffat’s lyricism all the greater heft (even when he sings "I wanna have sex on the beach" in a break between songs) and the bitter caught-you-cheating ‘Piglet’s breakdown into vengeful misanthropy – "you can’t get over your dead dog / well it takes one to know one" – is unsettlingly intense. One question, though, if Aidan was always that pissed, how did he remember all the words? – Luke Turner

Wire – Document & Eyewitness

(Rough Trade 1979-1980)

"I want ’12XU’", shouts a fan before Wire launch into ‘Witness To The Fact’, neatly highlighting the point of this peculiar live record. Recorded at the Electric Ballroom and Notre Dame Hall in London at the end of the first phase of Wire’s existence, it saw them winding up the simpleton punk audience who wanted only their clipped minimalism to jump up and down to by playing mostly new material from behind a sheet – or as the LP sleeve has it "Sheet 6×12, makes regular circuits around performing area, entry and exist only possible behind sheet. Sheet." That’s not to mention oblique, surrealist stage descriptions: "vocalist accompanied and lit by a goose". They taunt the audience too – a few chords hint at 1978 track ‘Heartbeat’ in ‘5/10′, eliciting cheers from the crowd. The song never arrives. ’12XU’ is only delivered as a fragment. There’s a lot of heckling. Interestingly, some of this material – such as the aformentioned ”Witness’ and ‘Underwater Experiences’ – has been revived and repurposed for Wire’s next studio album Change Becomes Us, the echoes of three decades ago living on as the band, bloody-minded as ever, continue to move forward by turning these fragments into modernist pop.

Luke Tuner

Iron Maiden – Live After Death

(EMI 1984 – 1985)

Live albums can be many things – farewells, documents of musical decline, even (once upon a time) secretive bootlegs passed from fan to fan like musical porn. Just sometimes, however, they are all about Fruit-tella, table tennis and barely disguised homo-erotic bonding. Musically Live After Death may or may not represent the moment Maiden became the complete behemoth – able to pack two hours of killers into a seamless, theatrical set – but personally, it represents the essence of my teens. Because of that album I cannot hear Churchill do his "Fight them on the beaches" speech in any context – and I’ve even been present at formal remembrance gatherings where I’ve heard it played – without wanting to air-guitar the opening riff to ‘Aces High’. Such is its completeness that for years it gave Long Beach Arena, where it was recorded, Valhalla status in my head. But it will stay with me always because it is the album my mate Chris and I wore out in his garage, high on sweets as we played endless table tennis. For the riffs & the rallies provided the means for two boys (one of whom wanted to be a girl) to talk about what really mattered: the sexual allure of spandex, what girls want and who we were going to be when we grew up.

Rachel Mann

Kevin Ayers, John Cale, Eno, Nico – June 1, 1974

(Island 1974)

So Kevin Ayers came back to London, after a long stay drinking wine in the south of France, to record a new album. It was the summer before his 30th birthday, so he rounded up some art/rock/whatever friends who were in town, and threw together a gig at the Rainbow in Finsbury Park. Besides Ayers, Cale, Eno and Nico, Soft Machine chum Robert Wyatt shows up on drums, and Mike Oldfield plays guitar. It sounds slapped together, for all the stellar cast. The music swings from Eno’s preening yelps to Ayres and Cale’s sleazy off-kilter blues to Nico’s interminable cover of the Doors’ ‘The End’, with lots of musical-theatre-caliber session singers filling in for extra drama, and am-dram at that. But who cares; instead of the supergroup this could have been, here is proof that even the artiest of art rock stars are perpetual lazy poncing teenagers, deep down. June 1st, 1974 is lovingly known as the ACNE record for more than one reason. It really should be shit, but the combination of awkwardness and swagger keeps it fun. Then there’s the backstory, which is about as ridiculous as the one for Rumours. The cover photograph says it all: Cale and Ayers are sort of squinting and grinning at each other, faces puffed from a run of hangovers; Cale is allegedly pissed off because he caught Ayers in bed with his wife the night before. Meanwhile, Eno’s kissing Nico on the forehead, and the pair of them look like a couple of waxy rouged mimes from a needle park in Rotterdam, left to melt under stage lights. June 1, 1974 is a kind of inflection point for early 70s excess and self indulgence: most of the principals would spend the rest of the decade seeing how much further they could take their boozing and drugs, their weary Euro-decadence, their orchestral fantasias, and their studio brilliance. But June 1, 1974 is as unguarded as the punk that was supposed to displace this sort of thing wasn’t. Not really. And even if you don’t care about official or unofficial rock history, this still sounds like goofy summer fun.

Emily Bick

Carter Tutti Void – Transverse

(Mute 2011)

One of the most intriguing moments of Transverse arrives five minutes and twenty-two seconds into ‘V2’, when Chris Carter, Cosey Fanni Tutti and Nik Colk Void’s chugging wall of mechanised noise is joined for precisely a bar and three quarters by Ableton Live’s default metronome sound. An audio routing accident, or a deliberate wink to the beatmakers in the audience? Neither answer seems particularly plausible, but what makes Transverse so arresting is the extent to which the answer doesn’t matter. Where the mainstream live album employs a raft of studio tricks applied after the event to make the recording sound more ‘live’ than live, Transverse makes a virtue out of those parts of the live music experience we typically try to ignore: the high-pitched whine of a feedback loop, the ambient chatter of punters between songs, sub-bass bottoming out the woofers. These elements are folded into the improvised songs/movements of Transverse not in order to demonstrate the recording’s ‘realness’ (as a bum note might survive in a live album to ‘prove’ its authenticity) but to render the question of intent irrelevant. The show’s genesis reveals an openness to happy accidents: skeletons of the individual pieces were composed in advance in the studio, giving the trio room to flesh the tracks out in live performance. The CD version of Transverse wisely includes just one track in its ‘original’ studio form: enough to show us how the magic trick was pulled off without diminishing the listener’s sense of wonder that it happened at all.

Chad Parkhill

David Bowie – Stage

(RCA Victor 1978)

September 6, 1997

"Should the shiny side be up or down?" she asks, tearing a strip of aluminium foil from the serrated side of a cardstock box. "Shiny side up, sunshine. You want to see your beautiful face, don’t you?" I reply. "I don’t think it actually matters," she mutters. But we’re 19, and not really listening to one another. I finish flipping the record and wheel around on the worn-down carpet. I take the foil from her porcelain hand and fold it lengthwise a few times, like a paper airplane left unfinished. With one hand, she taps out a thin line of off-white powder down the foil’s centre groove. With the other, she lifts a hollowed out biro to her lips. "I would be king and you would be my queen", I sing, taking her by the hips. The lighter ignites. A soft strand billows up and quickly disappears into the biro’s broad end. The smell of burnt sugar and chemicals fills the air. Her eyes slacken back in their sockets. The record pops and crackles. "Why do we have to listen to this now? We’re gonna to hear it live in a few hours anyway," she slurs, her words punctuated solely by staccato puffs of blue smoke. She passes me the pen, and I inhale my long ribbon. "We can be heroes, just for one day." Mr. Bowie and I exhale in unison. "Why is the D side on the back of the A side?" she asks, her brown eyes transfixed as the record spins. "Because it’s the deciding side, dear. If you don’t like the A side, you can skip B and C, and go straight for the D sider. I don’t fucking know. But we should probably go." We collect the tickets and exit, the front door slamming behind us.

January 7, 2013

The front door opens, and I cross the threshold of my empty home, resting a bag of groceries on the stove, shaking off my snowy coat and boots. I put a record on, beginning uncharacteristically with the D side. David Bowie’s Stage – I haven’t heard this in years. He’s got a new album coming out. I wonder if it’ll be any good. Who cares? It’s already fucking great, I think. I shift the groceries to the counter and put the kettle on to boil. I toss my snail mail onto the table, along with a handful of pamphlets a friend gave me over coffee earlier in the afternoon. "We can be heroes!" the very same Bowie bellows, my eyes resting now on a leaf of blue photocopied paper which reads, "Just For Today".

Ryan Alexander Diduck

Iggy And The Stooges – Metallic K.O.

(Skydog 1973-1974)

Metallic K.O. is the punkest album ever made, and the sound of my favorite band choosing a glorious death in battle. Iggy And The Stooges, on the verge of their final collapse, return to Detroit. They play to hostile crowds dominated by a biker gang called The Scorpions, who hurl abuse and eventually a barrage of missiles, ranging from eggs to bottles to shovels. Iggy replies: "You can throw your goddamn cocks and I don’t care." The Stooges fight back. They push the notion of a "song" to the brink of collapse, ploughing through sprawling jams as their leader dodges, ducks, and spits ad-libbed venom at the audience. It becomes clear that Iggy’s grunts and exclamations were never just throwaways – they’re what his vocal style is all about. When he repeatedly calls out the "butt-fuckers tryna run my world" or starts screaming "keep your hands off of me!" he’s no longer delivering lyrics, per se, just the pure sound of rage. The heart of this album, though, is ‘Gimme Danger’, dominated by Ron Asheton’s booming bass riffs. Even in the depths of abjection and despair, the Stooges reach out for beauty and seize it. Even as he pushes himself towards the breaking point, Iggy calls out, "I’m gonna live." Metallic K.O. is the great mystery at the end of the Stooges’ death trip. It’s about passing into the Other Side and coming back again, still dancing.

Pavel Godfrey

Diamanda Galas – Vena Cava

(Mute 1992)

Live, the avant-garde all-too-often conforms to the cliché of a load of bald blokes looking at one bald bloke making very bald, blokey noise. Not so with Diamanda Galas. Encountering her in concert is like being pulled through a psychic hedge backwards, an intense and moving experience that, when I saw her in Brighton in 2009, reduced to me to tears and seemed to warp time. You might think this presence would be impossible to capture on tape – not so, as Vena Cava abundantly proves. Presented in eight parts, the performance (recorded at The Kitchen, New York in early spring 1992) was inspired by by the writings of Galas’ brother Philip-Dimitri, a poet who died of AIDS in 1986. The contemporaneous programme notes also explained that it was an exploration of "the relationship between the dementia of severe depression and what is referred to as AIDS dementia." Much is made of Galas’ formidable vocal range, but going on about X-number of octaves does not do her justice here. She conjures a chorus out of thin air, different voices, some surreal, some everyday, spiralling around in a frenetic gabble, fragments of conversation; an unravelling of life. Rarely does something so harrowing feel so human.

Luke Turner

The Quietus Writers’ 40 Favourite Live Albums Unranked

- Electric Masada – Live At The Mountains Of Madness

- Siouxsie And The Banshees – Nocturne

- Neil Diamond – Hot August Nights

- Sun Ra & His Arkestra – Live At Montreux

- The Cramps – Smell Of Female

- The Velvet Underground – 1969: The Velvet Underground Live with Lou Reed

- Ramones – It’s Alive!

- Spiritualized – Royal Albert Hall October 10 1997

- Judas Priest – Unleashed In The East

- Fela Ransome-Kuti And The Africa ’70 With Ginger Baker – Live!

- Björk – Live Box

- Talk Talk – London 1986

- Donny Hathaway – Live

- Cardiacs – All That Glitters Is A Mare’s Nest

- Depeche Mode – 101

- Fields Of The Nephilim – Earth Inferno

- Talking Heads – Stop Making Sense

- Curtis Mayfield – Curtis/Live!

- Tim Buckley – Dream Letter: Live In London

- Albert Ayler – Live In Greenwich Village – The Complete Impulse Recordings

- Wilco – Kicking Television: Live In Chicago

- Neil Young & Crazy Horse – Live Rust

- Hawkwind – The Space Ritual Alive In Liverpool And London

- The Fall – Totale’s Turns (It’s Now Or Never)

- Dr Feelgood – Stupidity

- Coil – …And The Ambulance Died In His Arms

- Sepultura – Under A Pale Grey Sky

- James Brown – Sex Machine

- Sunn O))) – Domkirke

- Miles Davis – Agharta

- Throbbing Gristle – Heathen Earth

- Moritz Von Oswald Trio – Live In New York

- Arab Strap – Mad For Sadness

- Wire – Document & Eyewitness

- Iron Maiden – Live After Death

- Ayers, Cale, Eno, Nico – June 1, 1974

- Carter Tutti Void – Transverse

- David Bowie – Stage

- Iggy And The Stooges – Metallic K.O.

- Diamanda Galas – Vena Cava