In Teatro Micaelense – a gorgeous theatre at the heart of Ponta Delgada, the capital of Portugal’s Azores archipelago – Ben Chasny sits stage right and unspools deep, resonant arpeggios on his acoustic guitar. He’s leaning forward, slightly off his chair, fixed in concentration, and his glance flicks back and forth between his instrument and his collaborator, Norberto Lobo. Sitting to Chasny’s left, Lobo appears as laid-back as his bandmate does tense, sloped over his own guitar – this one electric – with his legs loosely crossed. He interjects with a melody of his own. This one is spikey, off-kilter, discordant at first, as if attempting to throw Chasny’s steady acoustic loops out of whack.

Gradually, however, it emerges that the relationship between the two guitars is not antagonistic at all, that Lobo’s mercurial flicks and flourishes, his gentle jumps forwards and backwards in tempo, are actually finding pockets of space in Chasny’s playing that would be imperceptible to most other musicians. The result is a sonic lattice that is both beautiful and unknowable in its complexity – you might even call it heavenly.

The following 45 minutes of their show, part of 2025’s edition of Tremor Festival, continues to push the boundaries of a traditional two-guitar jam. Chasny takes lead on the next track, while Lobo manages to make his guitar sound like plunging whale song, echoing little motifs that he lifts from the other’s melody. Then, it transforms into something akin to a church organ, while Chasny unravels into a hypnotic drift. There are points where the two trade dazzling solos, and others where they dovetail together into something greater than the whole. It is, in short, a magnificent performance.

And yet it is another guitarist – in their eyes, far greater than they – that took them to this point: Carlos Paredes, the virtuoso who redefined what was possible to elicit from the traditional 12-string Portuguese guitar in a career that spanned from the 1950s to the turn of the millennium. Also maintaining a parallel public service career, working in the radiography archive of a Lisbon hospital until the mid-1980s, Paredes spent 18 months in prison during the dictatorial Estado Novo regime, owing to his membership of the Portuguese Communist Party. When he died in 2004, a national day of mourning was declared. Chasny and Lobo were brought together to collaborate to mark this year’s centenary of his birth.

With Tremor Festival providing a residency in Ponta Delgada for them to explore creative ideas, before the two embarked on a short Portuguese tour that culminated with that magic at Teatro Micaelense, Chasny and Lobo quickly saw the futility in attempting a straightforward set of Paredes covers. For one thing, he’s such a towering figure that you sense such a direct approach would fall flat. Secondly, it quickly became clear during the residency that their creative partnership was taking on a scope beyond the original brief – other influences they were sharing back and forth, their shared love for other guitarists who have pushed the instrument’s boundaries with the same attitude that they do today.

In both the live performances and an already-recorded studio project to come, it’s Paredes’ spirit, as much as his sound, that has guided them, the two explain, speaking to tQ in their hotel foyer in The Azores, a few hours before their performance.

Norberto, could you give us an idea of just why Carlos Paredes is so revered in Portugal?

Norberto Lobo: Well, have you listened to his music? That’s why. He’s a genius. It’s just so mind-blowingly good that he had to become a hero.

Ben Chasny: I doubt that Norberto, having grown up with it, can really step outside of that. For me, and this is very superficial so excuse me, the first time I was here in 2004 he was introduced to me as being to fado what John Fahey was to folk music, as far as taking the form and expanding it and making it one’s own. And then I started listening to and then slowly getting sucked into the world that Norberto’s talking about.

NB: He’s kind of the soul of Portuguese music, you know? It’s hard for me to have a distance. I can’t really listen to his music with fresh ears.

Is it like asking someone from Liverpool why The Beatles are important?

NB: Kind of, yeah. It’s our Beatles, Jimi Hendrix and Aretha Franklin combined in one person.

Ben, can you tell us more about your first impressions of his work when you were a newcomer?

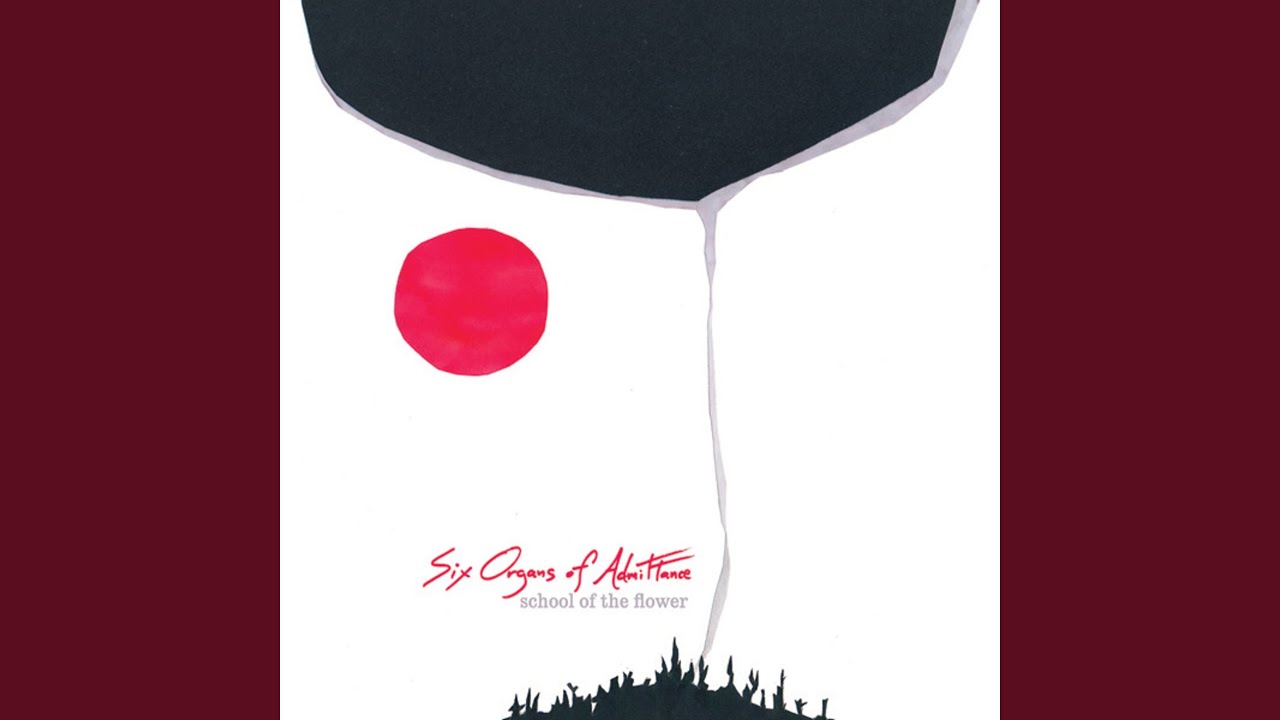

BC: I hadn’t heard anything like it before. It had like, this perfect combination of stateliness and absolute passion. Plus, it had a technique I’d never heard before. So, from a technical aspect, I could listen to it and from an emotional aspect, I could listen to it. All in one. I just dove in pretty hard, yeah, and then I dedicated even a song on my School Of The Flower record [‘Lisboa’].

You were also heavily involved in Drag City’s reissue of two of his albums, Guitarra Portuguesa and Movimento Perpétuo.

BC: There was a fella named Fred who was Portuguese and had just got hired at Drag City at the exact same time I got signed to them, and it was this double attack of ‘Get this out!’

Why was it so important to do so?

BC: I just thought it was a new sound that a lot of people who were into folk guitar music would have heard – especially in 2004, when that fingerstyle stuff was getting more and more popular, but it hadn’t quite reached the point where major labels were putting it out. I thought, ‘We’ve got to have more flavour than just Tacoma style or Bert Jansch, there’s all sorts of different guitar playing out there.’ I was seeing things get very narrow in that genre.

How have you been approaching the music you’re making together?

NB: Well, we always thought it would be more of an excuse to be inspired to make music together. From the beginning we decided not to play [cover versions] of Paredes’ music – also because we probably can’t, it’s too hard!

BC: We’d have to ask for a three-year residency.

NB: We immediately started making original music, which we both thought would be more interesting.

BC: When the record comes out, I don’t think it’ll be really tied to [Paredes], except that that was the emphasis for everything.

NB: It’s the anniversary of his death, and he’s being celebrated this year, so it was kind of an excuse, to be honest.

What does the music you’ve been working on sound like?

NL: Like two guitars jamming.

BC: It seems like, whenever you have two guitars, there are sort of these blueprints, like ‘Let’s do the Bert And John record, you be Bert [Jansch], I’ll be John [Redbourn],’ and we try to not follow them for the most part. Also, Norberto’s playing electric, so that’s kind of a fun thing. He’s also been turning me on to music that I hadn’t heard before as well some guitar players, so I’ve tried to incorporate that immediate inspiration, translating them for myself, and then presenting them back to him.

What inspirations do you mean?

BC: Like D’Gary, a Madagascan guitar player I hadn’t heard of. So that was part of it, you know. There was the residency, getting up in the morning and going to work, but it was also at night, getting to know each other. You know, when you’re having a few beers and are turning each other on to some music, like, ‘Oh, you’ve got to hear this. You’ve got to hear that.’ Becoming good friends. Coming up with things like ‘This is inspired by what you just turned me on to.’ So it was a real friendship thing as well.

Is it getting further and further away from the original brief?

BC: When we get together and write songs, yeah, but not really performance wise, performance wise it’s still a tribute.

In what way?

BC: Well we do play one [Paredes] song. But also, it’s one of those things where you’ve absorbed so much of his style that you don’t really sound like it, you know?

Paredes led a storied life, particularly his time in prison owing to resistance against the Estado Novo dictatorship. Is that any part of his appeal?

NL: For me, not at all. If you follow that logic, you will be a fan of every Portuguese artist from the 60s and the 70s. They were all in jail for being against the regime. I mean, my family has a history of being in jail for being communists, so that’s kind of normal. I couldn’t care less about the biography of artists. I think there’s a misconception there that somebody with a rough life makes better music, and I don’t think I need to know anything about the musicians I like.

BC: That said, there are some pretty amazing stories about him being in prison, walking around playing his songs on the air guitar because he didn’t want to forget his songs, and the other prisoners thought he was going crazy. That’s a good story! And as someone whose own country is currently suffering under a regime, it’s very romantic to think of an artist actually standing up, where today there’s not a lot of that in the acoustic guitar world.

NL: But here, as a Portuguese, you cannot romanticise Communism and Fascism. I think his music speaks for itself.

Six Organs Of Admittance and Norberto Lobo’s residency took place as part of Tremor Festival 2025. For tQ’s full review of the festival, click here. Next year’s edition takes place from 24 to 28 March, with more info available here.