© Mark Allan / Barbican

The programme says tonight’s performance of Remote Orchestra by the Aphex Twin is "Featuring The Heritage Orchestra and Choir"; which is good otherwise the audience would be facing an empty stage in the Barbican Arts Centre. Or that’s how it initially appears at least. Of course the Aphex Twin is no stranger to the concept of playing with audience expectations of what they want from their favourite electronic innovator. One could spend all day listing the number of events where James has taken the usual utopian acid house trope of the DJ as faceless anti rock star and twisted it beyond all sense. He has hired doubles to walk round clubs where he is DJing, freaking out the odd pilled up raver here and there. Giant Kangchenjunga demons with his face in garish acid colours would wander round the crowd of mid 90s festival performances like Teddy bears gone horribly wrong. At more recent raves he’s taken to using face mapping technology to superimpose his own face onto crowd members filmed and projected onto big screens in real time. And of course he’s DJ’d from a completely different location from where the evening’s dancing celebrants happen to be, his information beamed in electronically.

He is on stage however. He just happens to be hiding in plain view, in the only portion of the stage at the centre back which isn’t lit in low crimson. He is simply incognito behind a desk with mixing equipment on it. The idea of the DJ being less important than the crowd has been applied tonight to conductor and orchestra but not for idealistic reasons, simply so we can get a good look at the technology guiding tonight’s event, which requires conductor and musicians to be flipped around.

There is a Samuel Beckett play Acte Sans Paroles I which features a mime artist in a desert reaching for jugs of water which are lowered down above his head but always remain just out of reach no matter how hard he strains to reach them. This is drama boiled down to its most brutal and existential essence. When tonight’s performance of Remote Orchestra begins it is five times more interesting than this play.

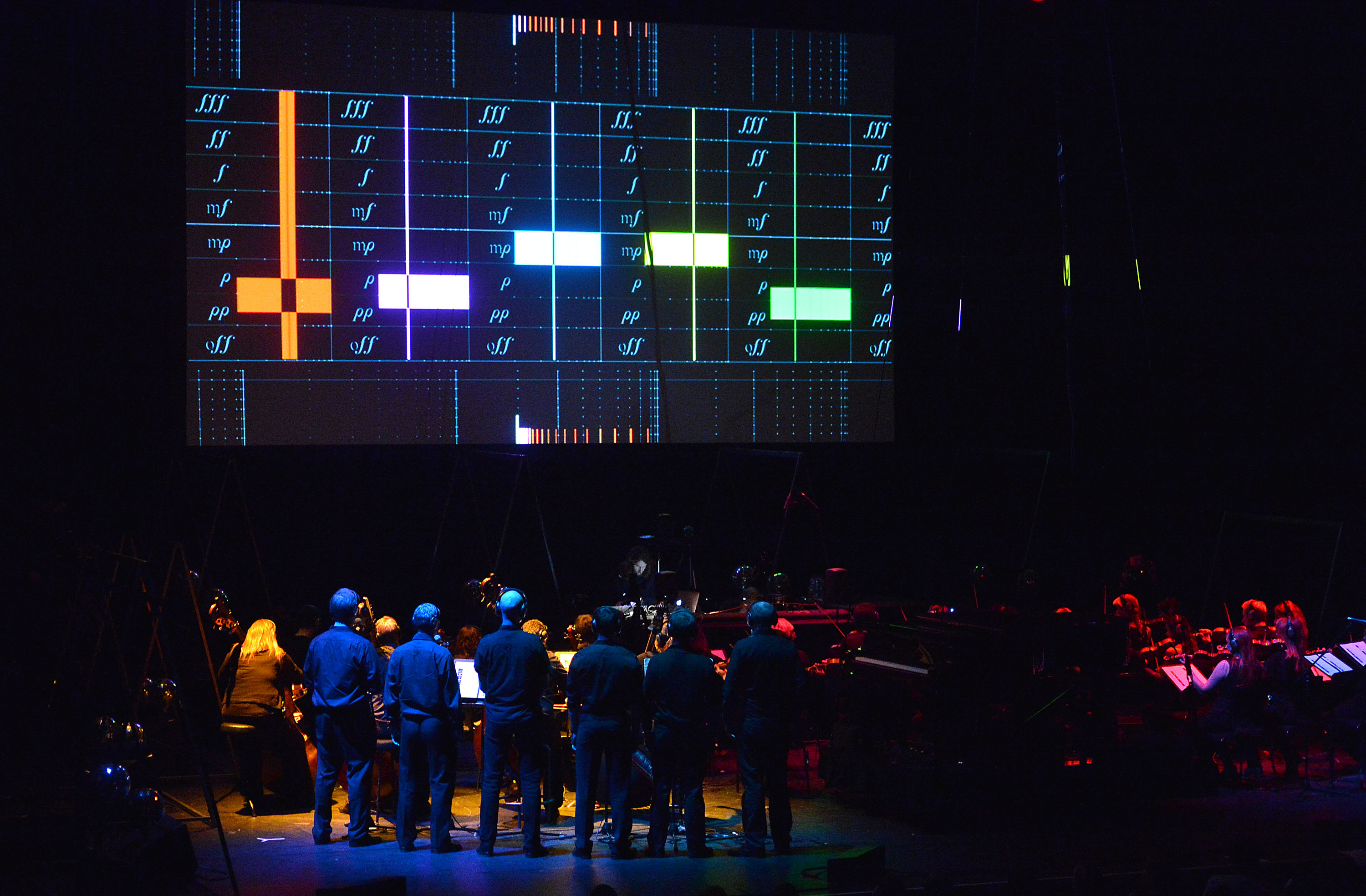

Richard D James manipulates a mixing desk-like contraption which is, in turn, represented by a large graphic display and projected onto a big screen above the stage which all of the string orchestra and choir are looking at. Five blocks of colour (representing the four sections of the orchestra and the choir) move up and down individual channels from noiseless, through pp to fff and the musicians follow suit with their volume.

The orchestra saw away at their instruments in a slightly arrhythmic manner but with the volume rising and falling across all five channels according to how the bars on the screen move. There is little variation in notes and it starts resembling Ligeti in a really roughshod way. Then however the lines in each section divide multiple times and additional lines start flickering across grids at the top and bottom of the screen controlling the actual notes being played by each section, as well as other techniques such as string scraping, and the sound begins to resemble actual Ligeti. Even for a short time the complexity becomes quite impressive and primitive minimalist tune structure begins forming but it is clear that this manner of marshalling music isn’t quite as precise as a sequencer and as melody forms, it just as rapidly falls apart. I’m too busy taking notes to see it myself but in a funny touch apparently the mask from the Scream films appears in the central blue column eliciting a literal response from the choir. Perhaps in a nod to the indeterminate composer Morton Feldman, a graphic of horseshoes appears although it’s hard to say what musical endeavour this is meant to encourage.

One has to feel for the more fastidious fans of both neo classical (the new complexity especially) and techno in attendance as it is quite obvious that there is a large element of chance at play tonight. Some of James’ moves on the MIDI screen are too fast, abrupt and violent for the orchestra to keep up with and the noise shifts between being a good approximation and a rough approximation of what is happening on the screen.

The Barbican has great pedigree for instigating these concerts that put producers and their audiences outside of their comfort zone. In fact it is 11 years since James played a ‘silent’ set to an audience wearing radio signal receiving headphones in the Tropical Conservatory. The idea for tonight’s show came from an Aphex Twin collaboration with Krzysztof Penderecki last year at the Polish Cultural Congress in Wroclaw, where the publicity shy techno and rave producer/DJ played notes on a MIDI keyboard which was projected to give visual cues to the orchestra.

© Mark Allan / Barbican

The piece barely lasts half an hour and if it sounds roughly like the music from the end of 2001: A Space Odyssey, then some people are acting like they’ve seen the Monolith during the interval. The intermission is to allow the second piece to be set up and it is interesting to eavesdrop on people queuing for the bar. "Jesus wept", says one man succinctly. "Unpleasant. Unpleasant in an interesting manner", says another. "I’m going to back in there buuuuuuuuut…" trails off another his face betraying the fact he really doesn’t want to. We live in interesting times when fans of songs such as ‘Ventolin’ and ‘Isopropanol’ (if indeed that’s what the crowd are) are mortified by the vaguely modernist racket made by an orchestra. But of course this is a good thing. (For some of this crowd) the time honoured string section has been recontextualised as a radical musical force once again, even if tonight’s fans are far to polite to actually riot like Parisians hearing Rites Of Spring for the first time.

And if the first piece was unsettling, so is the second but for very different reasons. A concert grand piano – a Yamaha clavinova which can be played remotely – is put on a platform suspended by cables a foot above the stage and winches swing it in a gracefully large arc from one wing to the other. James plays a simple melody by remote control. But the music is enhanced beautifully by the creaking of the wires it hangs from, several ropes running across pulleys, the natural phase and slight Doppler of the piano flying past backwards and forwards. The dampened and sustained chords feel like they are being processed but it is all the ambience of movement and simple machinery. With each swing the environmental noise shifts slightly, every pass is minutely different, like one of Basinski’s Disintegration Loops, it is the same but different, always reminding you that you are listening to an organic process, not so-called processed electronica.

It is beautiful, funny, thought provoking, hugely entertaining and doesn’t last nearly long enough.

The last piece – Interactive Tuned Feedback Pendulum, based on Steve Reich’s Pendulum Music – involves 18 mirror balls suspended from frames that look like they’re more used to supporting children’s swings. Nine helpers get them swinging through big arcs before walking off stage. The squeaking and metallic groaning that this produces is miked up and run through a mixing desk by James (who is now brightly spotlit) standing onstage at a desk, as green lasers are fired at the disco balls. For some reason he looks more at home in this bizarre vista. As the swings slow down inexorably, the alien sounding drones and groans slowly head towards a sludgy medium tone. The sickening lurch of the lasers around the concert hall becomes the slow undulation of futuristic bright green sea urchin spines.

Each of these performances is as much designed to focus your mind on one aspect of live performance as John Cage’s 4’33" is. The first makes you visualise an imaginary boundary or perimeter that marks the extent to which a conductor has control over an orchestra and makes us figure out what elements in classical music must be learned and practised by rote by musicians. The second makes us consider non-musical noise generated by a performance as part of the actual piece; it could as easily have included the scraping of sweaty finger tips on guitar strings, the breathing of brass players, instruments being placed on stands, guitar pedals being turned on, leads being plugged in… The final piece turns the tables. Normally one isn’t encouraged to think about the mixing desk during a live show but here it is, literally, centre stage. The audio sources are all much of a muchness and individually, not that interesting; and they get less and less interesting over the course of the performance making James work even harder to wrest dynamic texture out of the metallic creak and drone.

The premise of David Byrne’s new book, How Music Works is that contrary to popular belief most music is written with a specific venue and template in mind. While this is no doubt true of 99% of music I still don’t think it’s true for Aphex Twin’s non-rave work. It’s not clear whether his slightly confusing orchestra should be in the Barbican or at Jupiter Approach. Likewise his swinging piano could easily be suspended from the lofty dome of Istanbul’s Blue Mosque (if the scaffolding were removed first at least). As for the laser lit swinging disco balls, well there’s always Stone Henge. It would certainly be more apt than a load of old bongos.

As he leaves the stage to rapturous applause he gives a cheery double thumbs up. More! More! Bravo! More!

© Mark Allan / Barbican