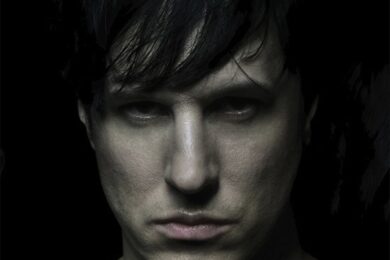

When I saw Atari Teenage Riot playing at this year’s OFF Festival, I couldn’t wait for the opportunity to talk to the man standing behind the Berlin-based, digital hardcore originators. The show thrown by the veteran sonic guerillas seemed more like a reconstruction than a reactivation. The fact that their approach to the sound and stage didn’t change throughout the years didn’t bother me at all, but the impact that used to start up riots in the streets of Germany, nowadays just forces people to move around like Twin Shadow was playing a disco set. It’s not only because the teenagers have changed, it’s also the fact that the guy who looked like the general of the New World Order dictatorship has lost a bit of his opinionated charm.

The chance to test his charm came faster than I would have thought. The fact that he was DJing at the Synesthesia Meeting in Wrocław a few weeks ago gave me an opportunity to ask all those questions that crossed my mind as I was watching ATR on stage, to get political and dwell on the subjects that most of the scene nowadays don’t even want to scratch on. The set in which he incorporated Freddie Hubbard, Sun Ra, Björk and Masonna – on the other hand – made me wonder if my perception of the OFF Festival show wasn’t a bit too harsh. The founder of Digital Hardcore Recordings, Thurston Moore and Merzbow remixer and Eat Your Heart Out representative is now working on some new material and touring intensely, and as such, we spoke over the internet; while that usually leads to curt answers and the lack of contact, this time it fitted perfectly well into the context.

Japan has just introduced the penalty of prison for illegal downloading and sharing music. Do you think it’ll set a precedent on the global music market?

Alec Empire: This has a longer history. Chinese bootlegs have always threatened the Japanese music industry as a whole. I think this is important to keep in mind. The situation is a bit different in each country. We will have to wait and see if people will actually be punished as hard, but it will definitely scare the majority off. I personally feel that it’s a waste of time to fight that battle. I see it like this: any artist can make his/her music available for free if they want to over the internet. So in my opinion to fight over the ‘freedom’ to download a song by pop artists who are mostly manufactured by big corporations is a waste of time. Any artist who is in control over his own work could always choose the free download option. The technology is in place. I personally respect it when someone does not make their work available for free, because they need to finance the production. Of course I hope that technology will always be ahead of the authorities and their laws, regulations and restrictions. I think the governments should stay out of this. In my opinion those from the entertainment industry who feel helpless because they want to ‘fight piracy’ but need new laws and regulations and such hard fines and punishments should invest their resources in inventing a technology that makes it work for them and convinces music fans to pay.

How do you approach the copyright laws? In the days of digital decay and increasing infiltration of the world wide web, what are the best ways of using the internet and not being used by it?

AE: I make sure I own the rights to my work. I have always done that since I started publishing my first songs at the age of 13. To give you an example, if a musician contacts me and asks for permission to sample parts of my music, I can always okay it. So it’s not a big drama really. Is it helpful when big corporations want to exploit your work financially, so you are protected from them? Of course. People keep forgetting this in the debate. It’s not about the kid in the bedrooms downloading a song or remixing it, it’s about opening the doors, so governments and multi-national corporations have total access to any idea that an individual can come up with. That is the threat and a danger to creativity. Why do I think that? Because I see already the best creative minds leaving the ship. I only care about creativity in this debate.

Is there a space in which you can – at the same time – launch an app for iPhone and support Anonymous?

AE: The iPhone app was a fun thing. It caused a controversy because Apple delayed the release in Germany because of the ‘Riotsounds’ audio player. This had more to do with ATR having an album on the index [list of censored material in Germany, which restricts who purchase the work]. So often the alarms go off when we do something. In this case it was also more about technical issues. If you have certain frequencies blast out of your iPhone, the speakers can be damaged. We left the audio player off and promised to add it when the issue is solved. But that was just the surface of what was really going on. Because this one album of ours, The Future Of War is on the index in Germany and as it means [that] it is forbidden to be sold or played in public, we entered a grey area in the case of the iPhone app. Because all our albums were in there for free, we were able to sneak that album back into Germany’s iTunes system. We do this kind of stuff for fun, find ways around restrictions.

Coming back to the digital decay theme for a second, it basically means that the more controlled and regulated the internet gets, the more people will avoid using it. I see the internet as one of the greatest experiments that shows that anarchy works. The sad thing is that it looks like we are missing this chance and will end up with something like a modern interactive television if authorities try to apply the rules of the non-virtual world. I think it should be the exact opposite way around. We must incorporate the ideas of the free internet into the non-virtual world!

Concerning the history with Phonogram Records raising the funds for the Digital Hardcore imprint, you could possibly write a book on "how to fuck the music industry while it fucks others". Do you have any advice for young artists starting the struggle in that market?

AE: Some people might get the wrong impression because these episodes are always highlighted in the media. I work on the principle that when both sides agree on a deal, both parties must come out winning. In the music industry there are too many people working who don’t share that approach; to screw someone over means, for them, that they achieved something. We must understand that the music industry always reflects our society. I come from an underground scene where people came together because they wanted to build an alternative to the status quo together. With this approach the biggest revolution in music happened in the last century: electronic dance music, techno and all its subgenres. If the music industry keeps selling old ideas disguised by new faces, it will not have a future. It’s not different to any other industry. My advice to young artists can only be ignore the glamour; most of it is promotion and it’s paid for. Don’t think that just because you hear something on the radio or on TV that this is a musical direction you must follow. The music industry of today is more top down then it appears to be. Make the music YOU believe in. It has to stay with you your whole life. Ignore fame, focus always on the music itself. It’s not as easy as it sounds.

The new Atari Teenage Riot album was released by Dim Mak, the label associated with commercial, straight-to-the-dancefloor productions and managed by Steve Aoki, a guy who asks for a dinghy and cakes with the label name in icing on his rider. Why have you chosen this particular imprint?

AE: You don’t want to know what I have in my rider… I like Dim Mak. They remind me of Grand Royal, the Beastie Boys’ label, who put out some of our records a decade ago. Dim Mak’s output is actually pretty wide. They have done very interesting compilations and also weird underground punk and hardcore stuff, like All Leather for example. Some people overestimate their role and assume they have a huge say in the creative process of Atari Teenage Riot. That’s not true. We always make our music exactly the way we want it, then we find partners who love it. With Dim Mak, this was exactly the scenario. They said they wanted to NOT keep releasing four to the floor dance records, even though this really works for them, due to Steve Aoki being a really successful DJ. Isn’t that good? Yes it is. They did a great job in supplying us with remixes. That is something I didn’t have on my radar enough. They found producers who did really cool remixes of ATR tracks. We respect each other’s opinions.

ATR reunited in the days of rising social awareness and civil disobedience, the Occupy movement, the riots, the Arab Spring. When you started in 1992, you started for a definite reason. What’s the aim for the new millennium?

AE: What is happening right now is the consequence of politics and many decisions that were made when we started in the 90s. The Euro crisis is one example. One thing is definitely on top of the list and this is freedom of anything that happens online. There is a war going on over who controls the internet. This will escalate and can lead to a surveillance state which will be very dangerous for all citizens. This discussion must happen in music as well, and of course in many parts of society.

The impact of ATR was partially based on the sonic shock. Do you think after the "the end of history" and the "shock doctrine" theories, and the scale of countries using shock to justify their actions, it could still be used to waken people up?

AE: I don’t think what we do is a "sonic shock" to people, it is about the physical energy that the audience gets from the sounds – that’s a huge difference. When one is shocked, one doesn’t react by moving and dancing, one would react with fear and would freeze.

ATR always seemed to use sound as a weapon – "riot sounds produce riots". Are you still searching for new methods of making specific impacts with the right tones and structures? Do you think about reaction of the audience while producing material?

AE: Yes, we do. A lot of that stuff happens more when we play live of course. That hasn’t changed much. This is really what drives us in Atari Teenage Riot. We focus on these types of sounds, and they have to function in the context of the lyrics. It’s a very unique approach of making music. It is actually the exact opposite of how most electronic music is produced these days. That makes it so challenging and exciting.

All of your creative work, from the Digital Hardcore days till the latest solo experiments, seems planned down to the smallest details. At the same time you always use noise and distortion, which are quite unpredictable sounds to work with. How do you approach this kind of sonic material and do you allow an element of fortuity?

AE: A lot of the music is programmed, so you have to think ahead and not just do trial and error, as they say. We don’t want to be lucky; we want to aim for an idea, then put that into reality. But because it is all programmed, we discovered right in the beginning of the group that the music can lose something in terms of energy. So by leaving space for experiments will always add ‘life’ to a song. But again, we don’t just turn on the machines and then see what happens. We focus on an idea, then it’s like our subconscious controls the machines. Very similar to how free jazz musicians would improvise. We really got this technique from those genres.

You still often use the Atari ST1040 and the digital hardcore aesthetics of sound. Do you think nowadays there is enough space to broaden the frames of the genre?

AE: We think there is. The good thing is that we feel now that we don’t have to respect the past as much anymore. That was the challenge with the last album. We knew it would be seen in relation to the 90s records we did. We don’t have to build that bridge anymore.

Most of the bands even nowadays don’t think like this, they are still building those bridges. New but really old rock sounds, retro productions and obsolete ideas still rule a huge part of the music industry. At the same time, it seems like we’re approaching the final fall of the majors and the model of the phonographic market as it used to be. Do you see an alternative paradigm?

AE: It’s hard to answer – right now the authorities are putting a very regulated internet in place, and even if the smart ones among us find other ways, I am afraid that the majority will have to adapt to the new laws which are coming. Japan was just the start. This will give the traditional music industry a boost again. Let’s wait and see.

So what are you listening to during these hard times?

AE: I love a wide range of music. Brainticket, Faust, The Monks… check it all out, it’s all rather old stuff.

Concerning the new stuff, how do you see the Berlin club scene nowadays, in an age of easyJet flights and party tourism? Is there still a link between how it looked when you started and today?

AE: Of course many things have changed. I think that’s a good thing. The whole Berlin myth and hype, though, still goes back to what many underground musicians, producers and DJs created 20 years ago. Anything that happens in the city is somehow related or put in context within that. What we are missing right now is Berlin innovating a new and fresh sound. This has not been happening for a few years now; that is not good at all. There are great locations for parties and club nights, but there is a lack of identity. The locations are about to go – this can’t be the only thing Berlin is known for.

What interests you most in terms of musical production at this moment? I heard from your management that you’re working on new material – what can we expect?

AE: I have a few projects ready to go… hard to describe – different to ATR and my previous albums. Let’s speak about it when they are actually coming out.

At the same time that you’re producing and touring with ATR, you’re also playing DJ sets. How do you approach this kind of artistic expression?

AE: I DJ in a very different way to most DJs out there. It’s not like the usual ‘artist’ who plays a few tracks or something; for me, DJing is about making a musical statement. But I also work a lot with the crowd. People often tell me that when they see me DJ, they understand why my music sounds like it does. I started as a guitarist first, then became a DJ. It’s very important for my productions, because I have created mixes on the fly over the past years which really made me approach my recordings and compositions in a new way.

One last thing – the Polish neo-Nazi movement raises it’s bald head from time to time and the last major accident happened in the town you played in, Wrocław. Do you think the name of the first track by ATR [‘Hetzjagd auf Nazis’ (“Hunt Down The Nazis’)] is still the best/only way to fight them?

AE: This needs a much longer answer than I can give you right now. But back in the day, and it has become relevant again over the past year in Germany, the authorities had ties with the neo-Nazi groups. There are many reasons for that – in some parts of Germany, certain types of people go to the police or the military. Politicians use fear tactics to get elected, often with manipulated facts. Growing racism is the consequence. We see this in many countries over the world. The good news is that Nazis have no future. Their ideas led to failure before. Why? Because people are networking all over the world. This extreme racism mixed with socialism simply doesn’t work because we are all connected as human beings. So this war is already won, but because Nazis try to fake reality, they get angry and aggressive when they are confronted with the facts. In our age many people are harmed by their violence, some are even killed. We never said that the track ‘Hunt Down The Nazis’ is the best or only way to fight them, but there is a point when lighting a candle for peace doesn’t achieve anything. We cannot negotiate with people who want to wipe out millions of people. We wrote the song in 1992 when Nazis burnt houses of asylum seekers [in Solingen, Germany], attacked them and killed some of them. The local police protected the Nazis and the conservative government let it happen to justify new emigration laws. We sent a strong message with this song and many people started understanding that when mainstream politics integrate views of neo-Nazi organisations, history starts to repeat itself. The Nazis in the 30s didn’t gain power over night, all these steps happened one after the other. We know where Nazi ideology leads: destruction and death. We must resist, and be prepared in case their ideas reemerge in a new costume; it looks more modern but the same dangerous thinking is behind it.